« It’s like driving a car at night. You never see further than your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way. » — E. L. Doctorow

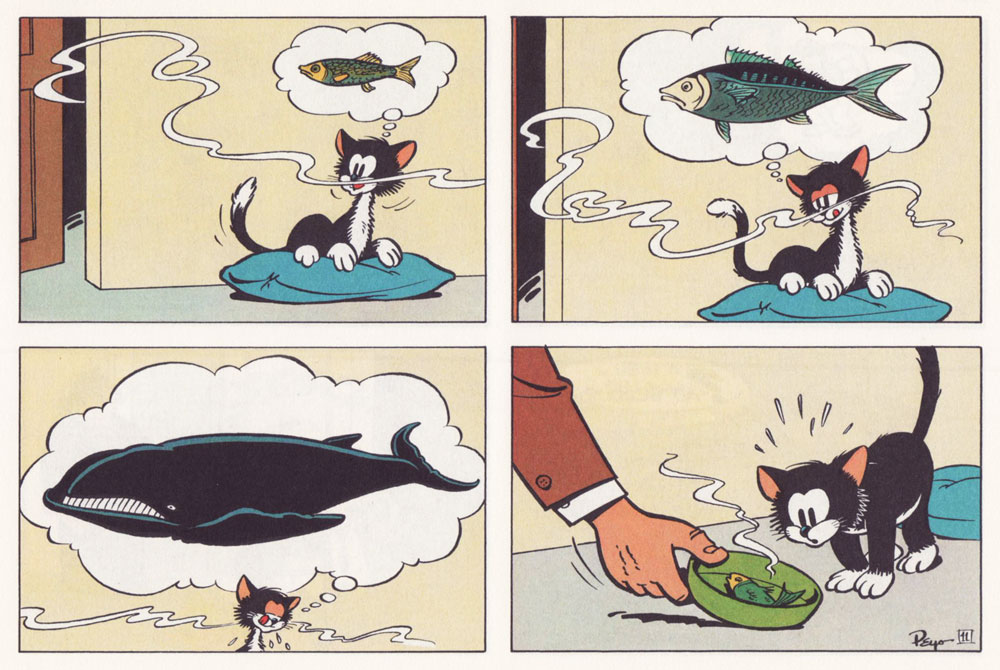

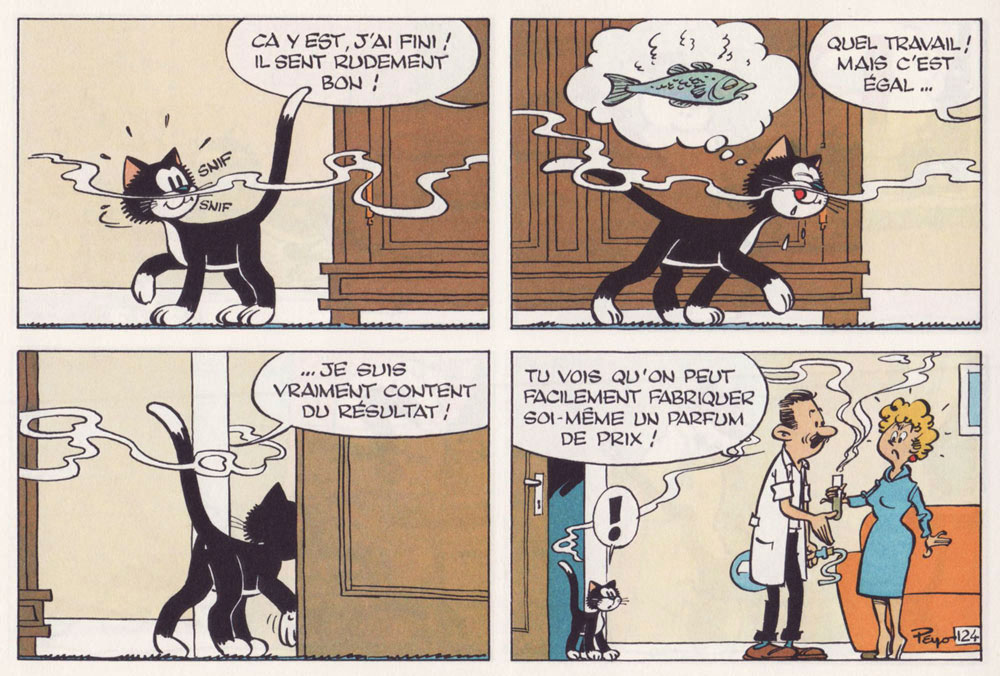

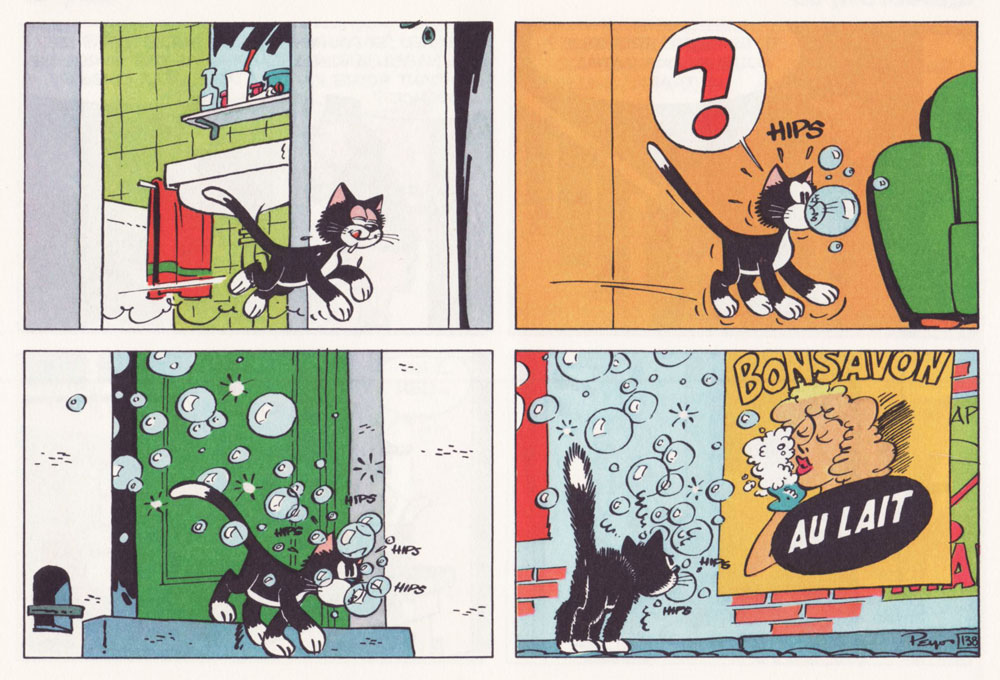

Once more rooting around Europe for properly atmospheric material, we unsurprisingly dig up some gold in Belgium, a land rife with longstanding traditions of the fantastic.

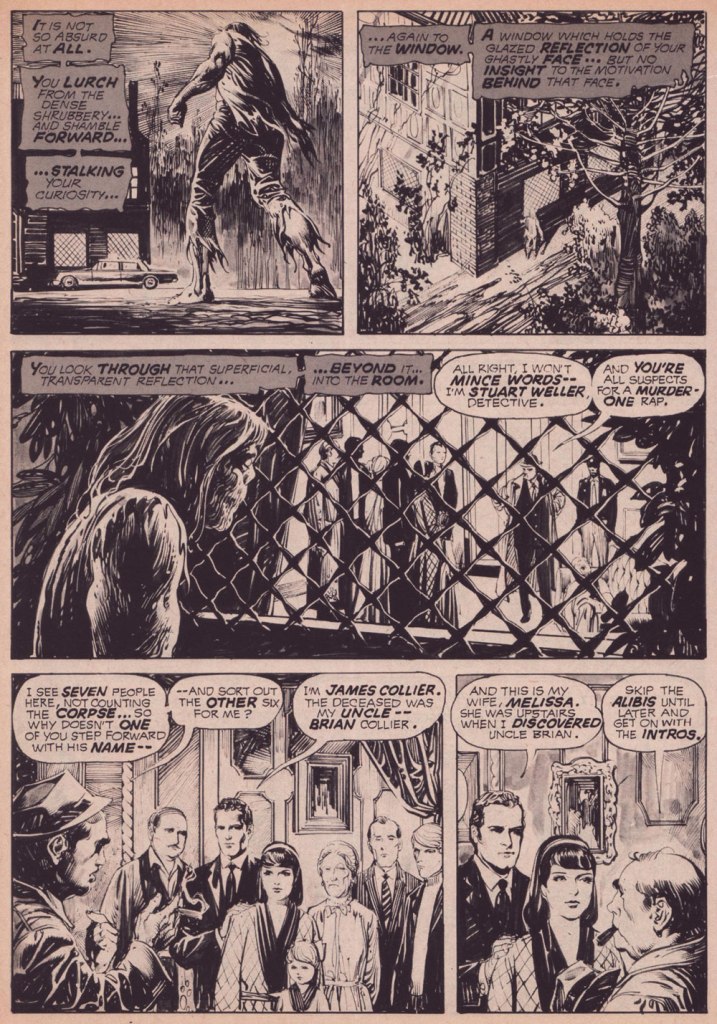

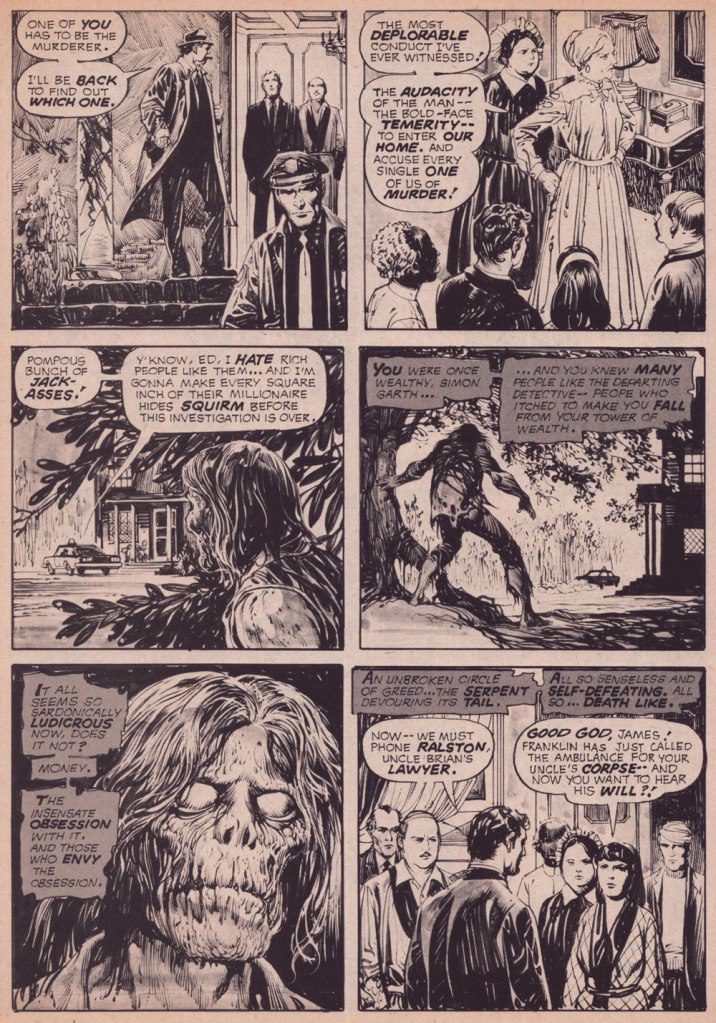

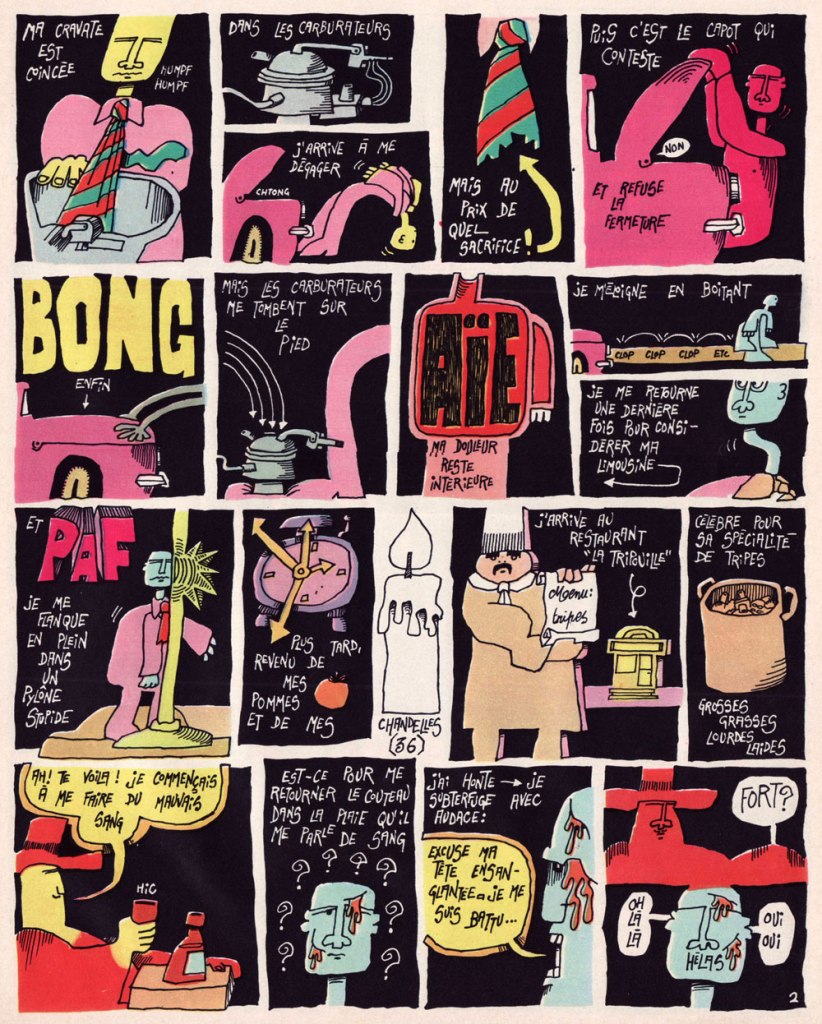

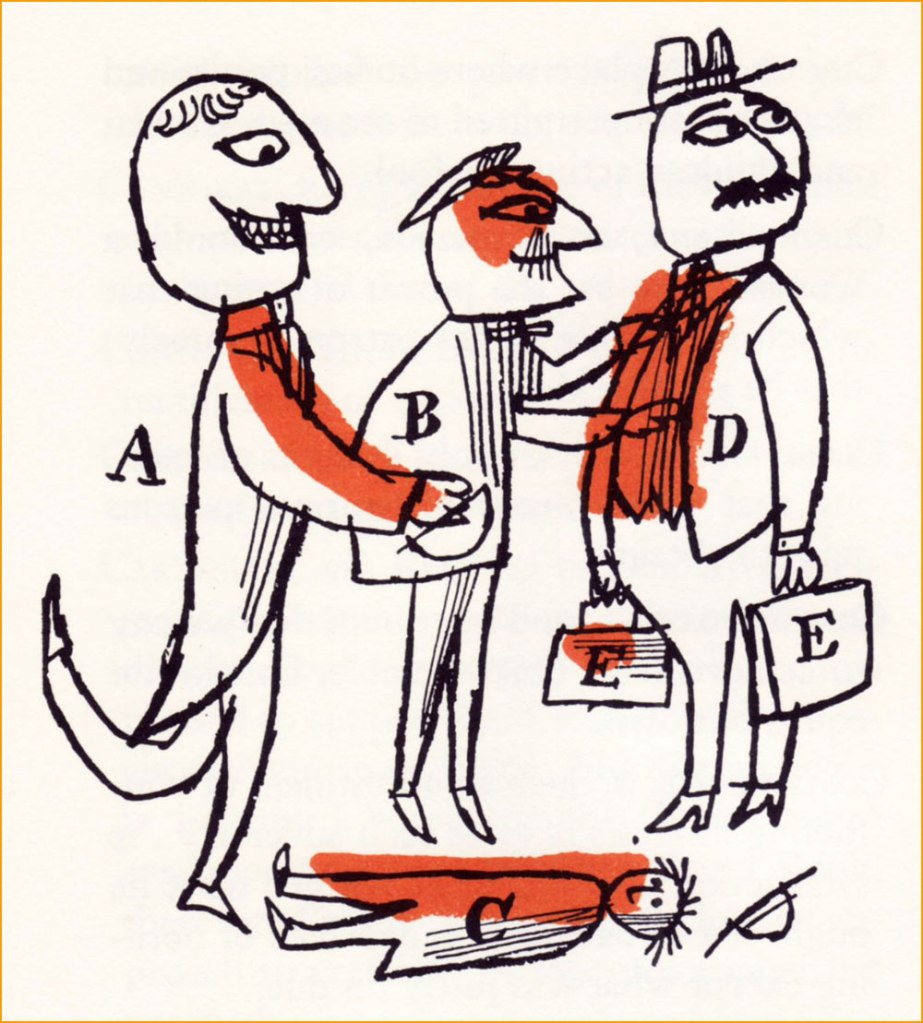

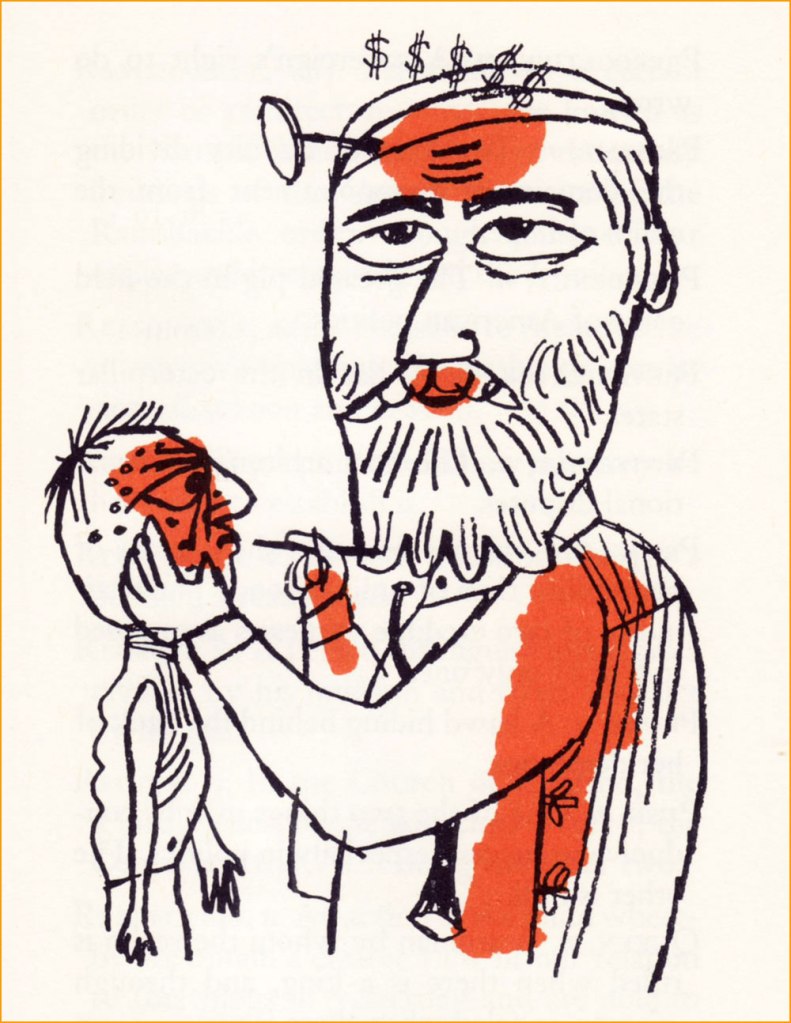

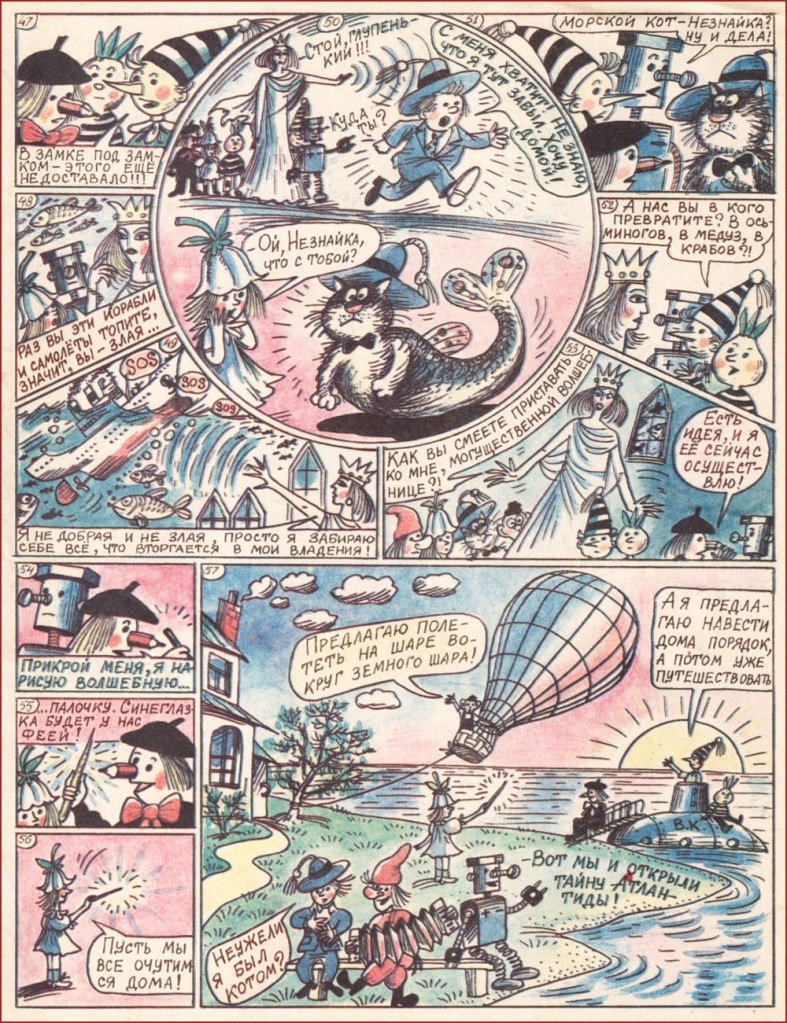

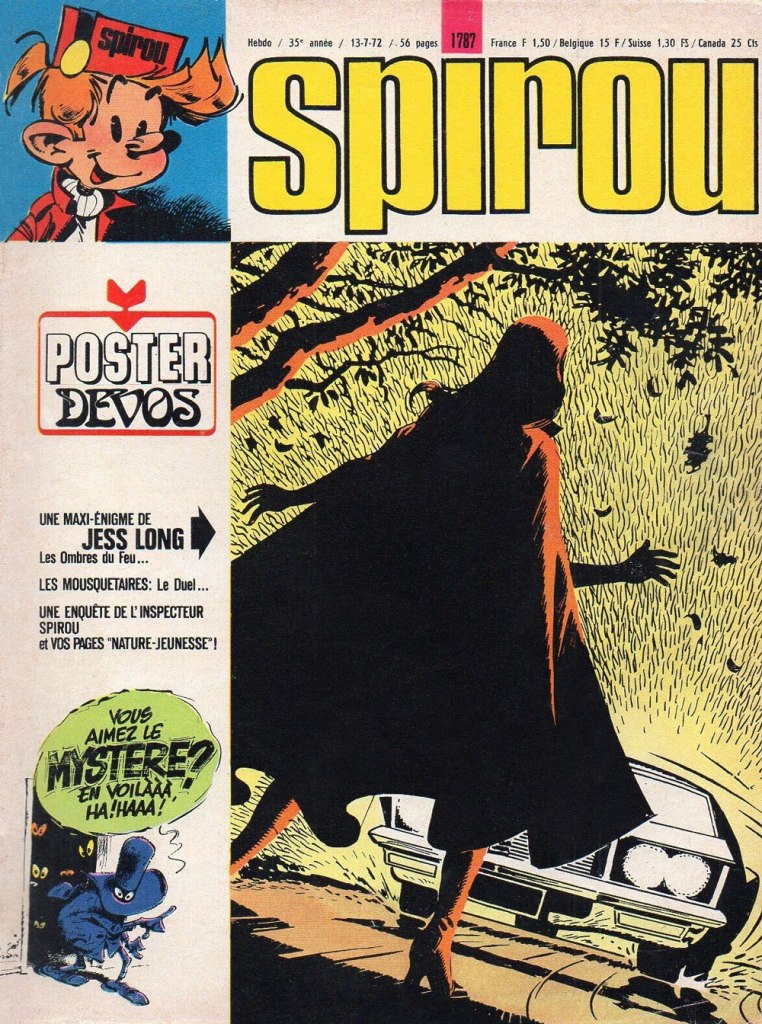

While there never were — if memory serves — any explicitly supernatural elements at play in Maurice Tillieux and Arthur Piroton‘s chronicles of FBI agent Jess Long’s colourful investigations, the creators used every opportunity to instill the oppressive fog of atmosphere.

While never a massive hit, the series had solid legs, lasting from its 1969 introduction in Spirou magazine, surviving Tillieux’s tragic demise in 1978 and finally coming to the end of its road with Piroton’s own passing in 1996.

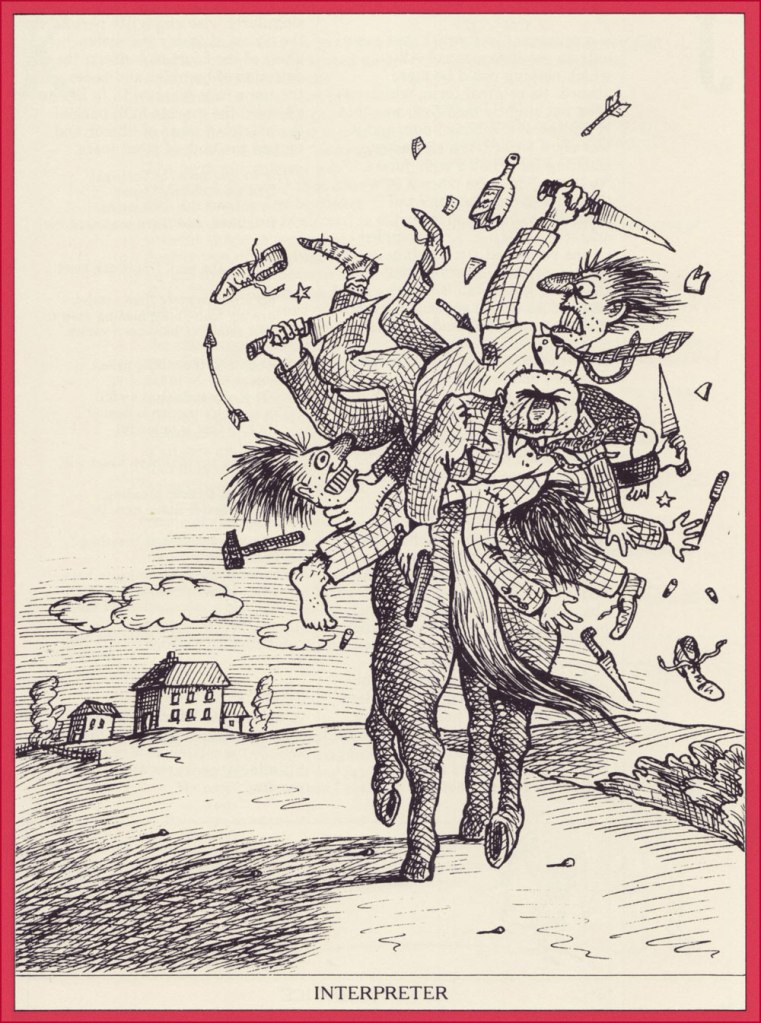

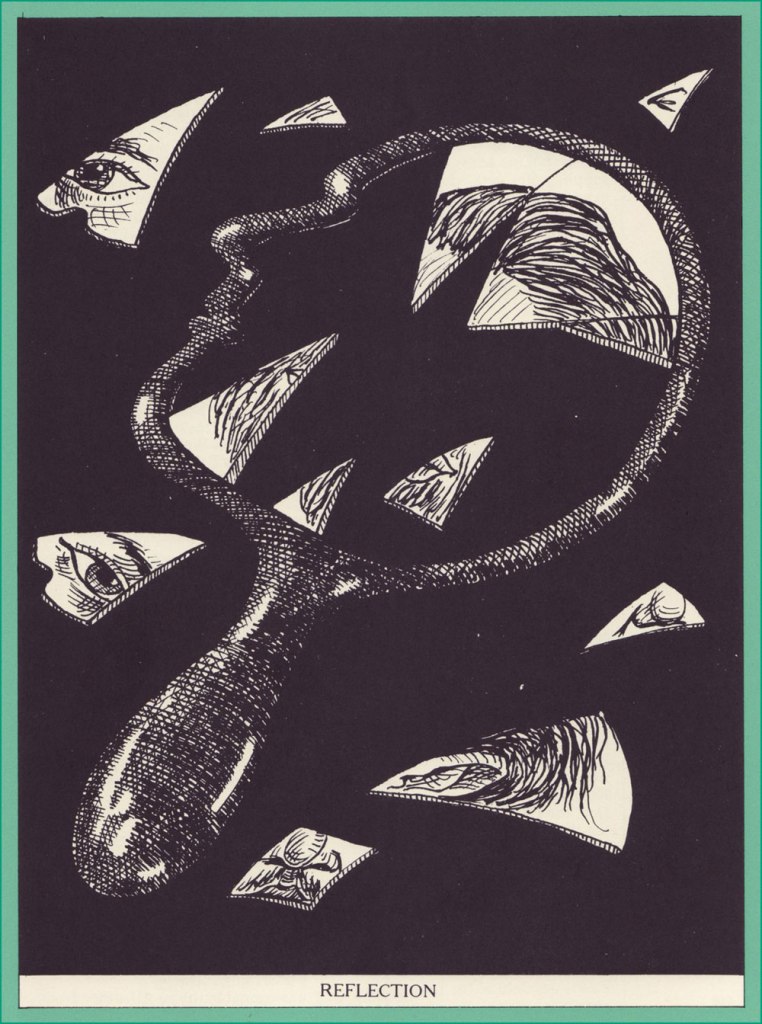

Today, we feature excerpts from Jess Long’s sixth investigation, Les ombres du feu (‘Shadows of fire’), from 1972. Fasten your seatbelts!

I’ve heard that Piroton’s style was considered a bit too ‘American’ to be that popular in Europe. Amusingly, it looked like nothing published in American comics at the time — I’d say his approach was a throwback to a mix of Bernard Krigstein and, say, Alex Raymond in Rip Kirby and Secret Agent X9 mode.

Something else worth noting about the Tillieux-Piroton collaboration: while Tillieux was the complete package — writer and artist — he was essentially forced, by some disastrously myopic editorial decisions right from the top at Dupuis (a stubborn failure to grasp that not every cartoonist can be his own writer) Tillieux had to almost entirely give up drawing, even on his own series, Gil Jourdan, to take on writing duties for a great many features. But since he was, one might say, the “Anti-Stan Lee”, he painstakingly storyboarded each page of his scripts, acting not only as scenarist, but also as metteur en scène. Thankfully, some examples of these fascinating breakdowns have survived. Check out this one and especially that one. -RG