« Our Betty Cooper is still the girl next door – she literally lives next to Archie. And she’s the blonde all-American girl; she’s so sweet and forgiving, gives people the benefit of the doubt and second chances, wears her heart on her sleeve. But she’s also incredibly broken on the inside, for many different reasons. » — Lili Reinhart

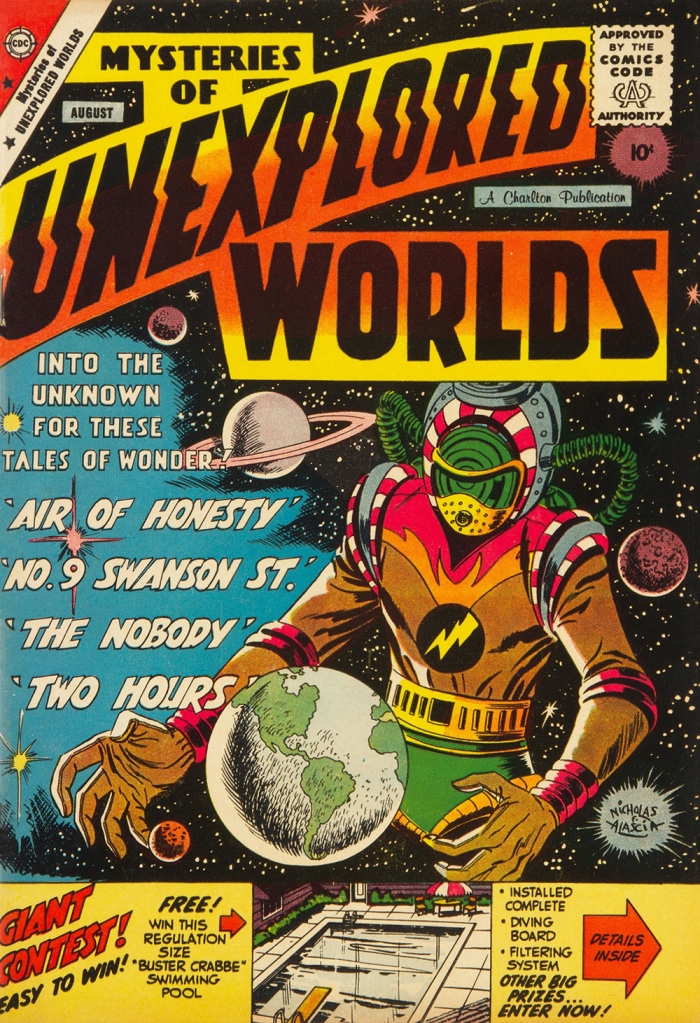

As a whole, comic book artists are not a happy lot, and for good reason. During the Golden Age, at least, there were countless publishers, so one could move around if unsatisfied with the working conditions.. even if meant finding out that things were rotten all over. After the mid-1950s, when the field violently contracted — you know the story — leaving scant players standing, you pretty much had to take the work, and the abuse, as they came. And certain publishers frowned upon ‘their’ creators playing what little remained of the field.

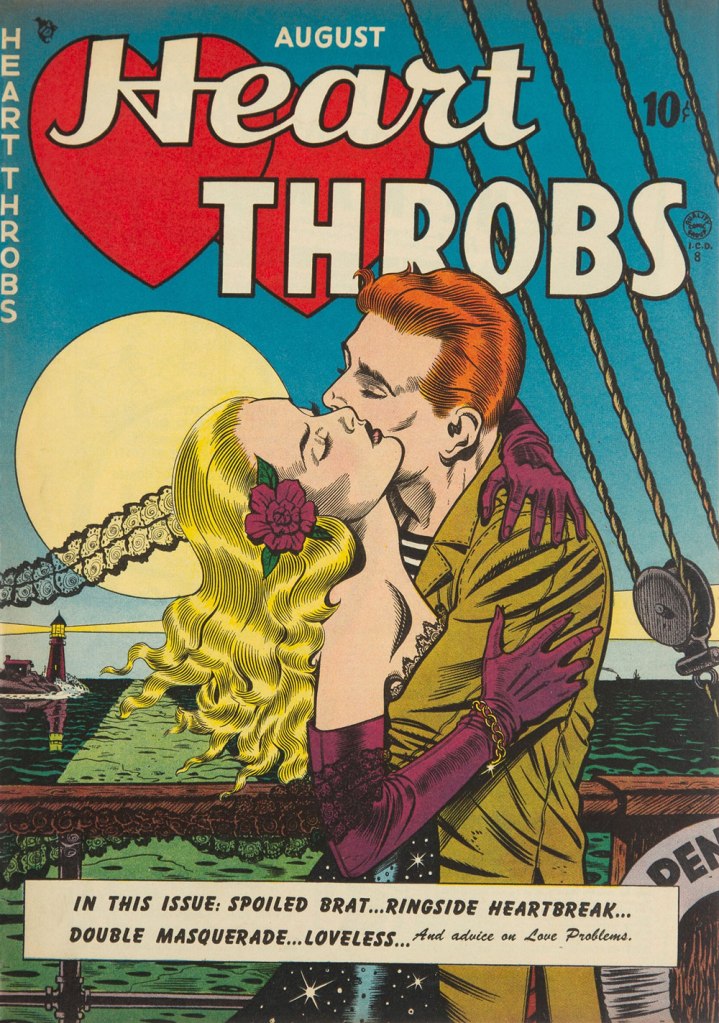

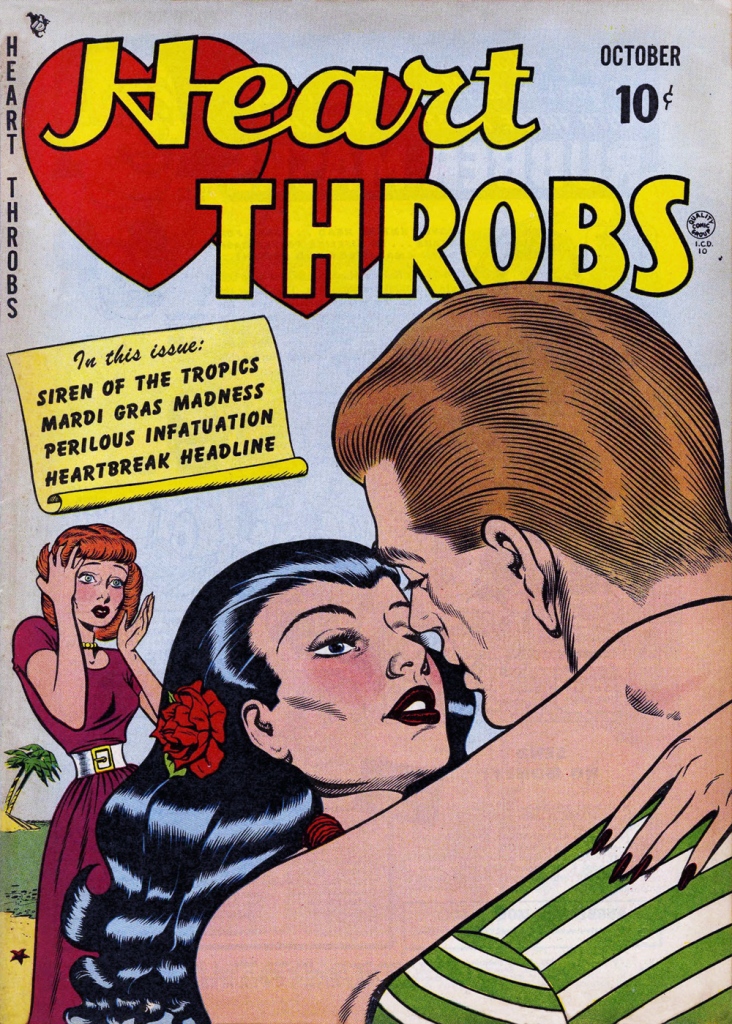

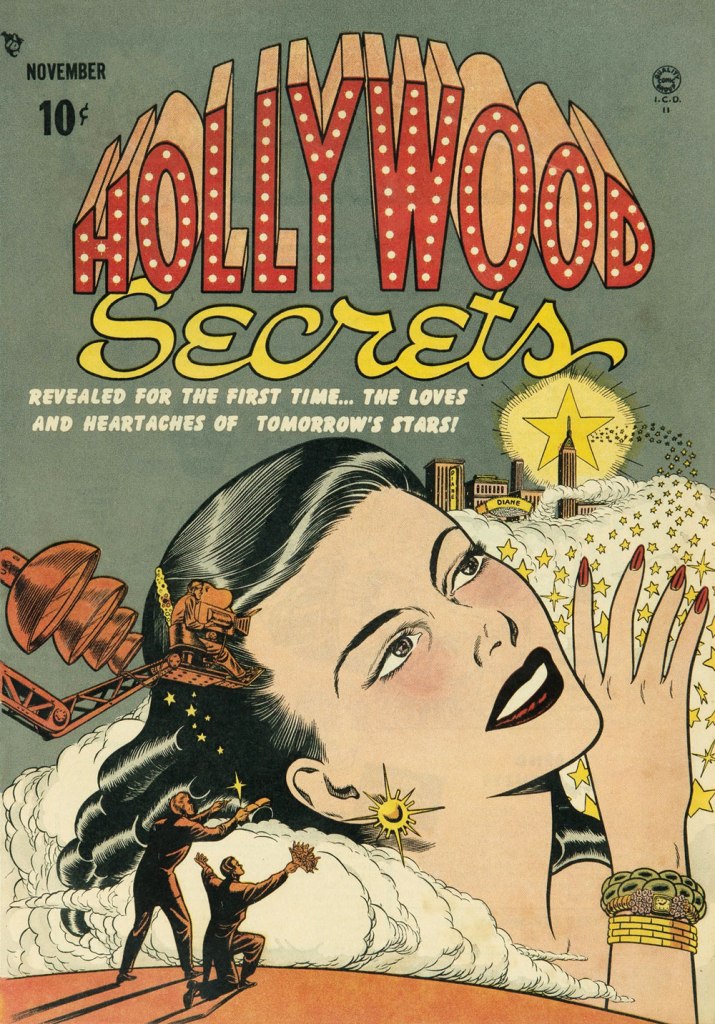

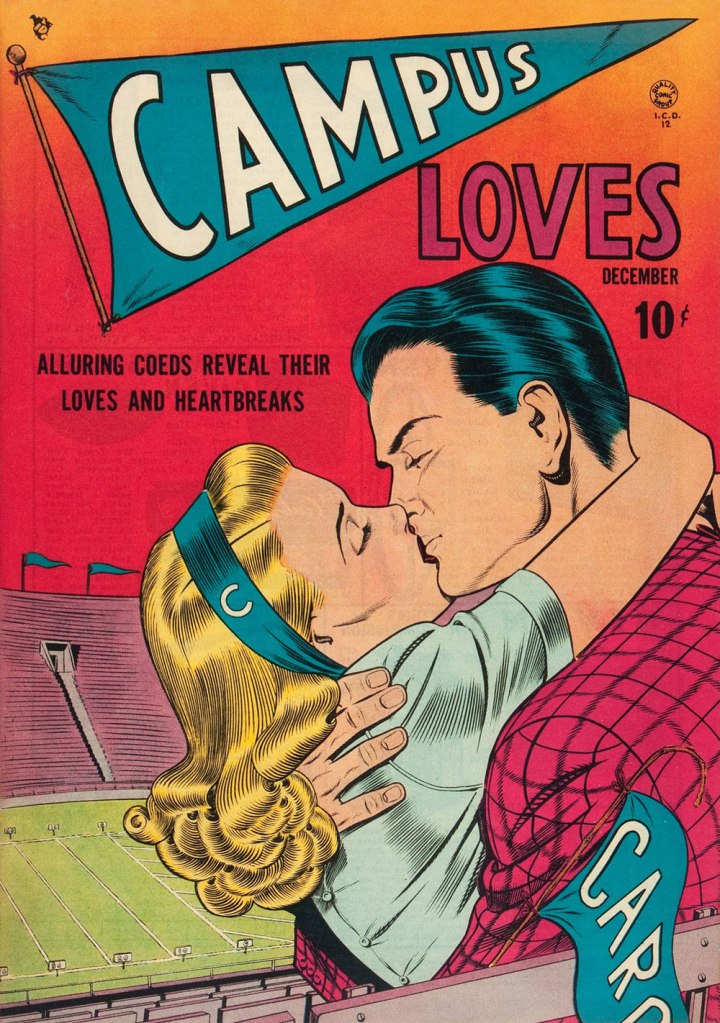

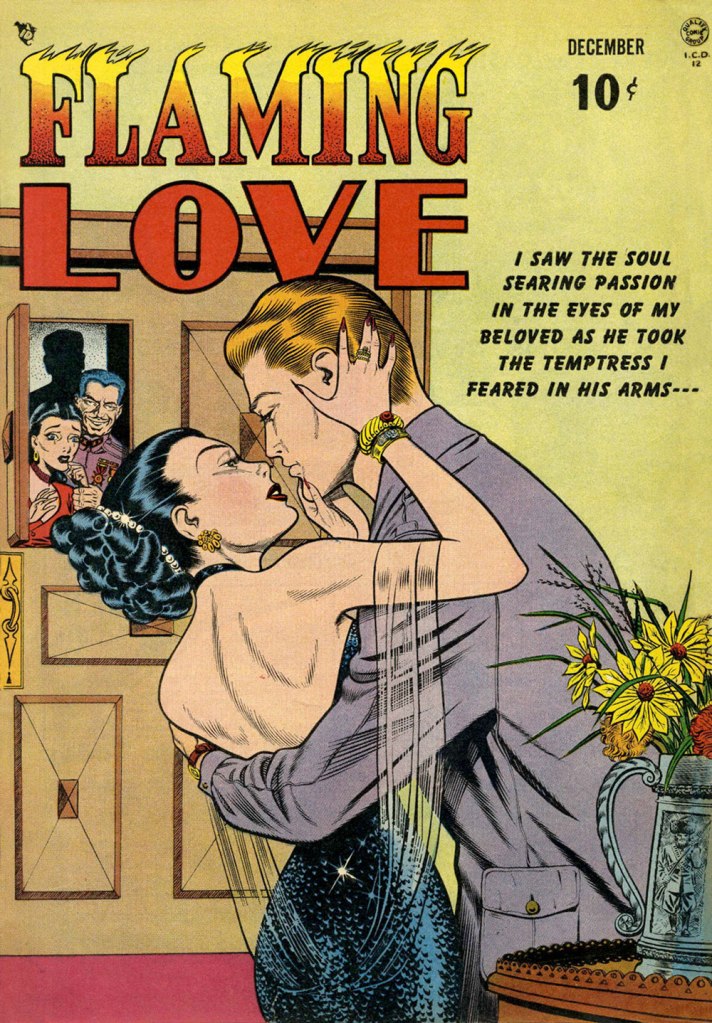

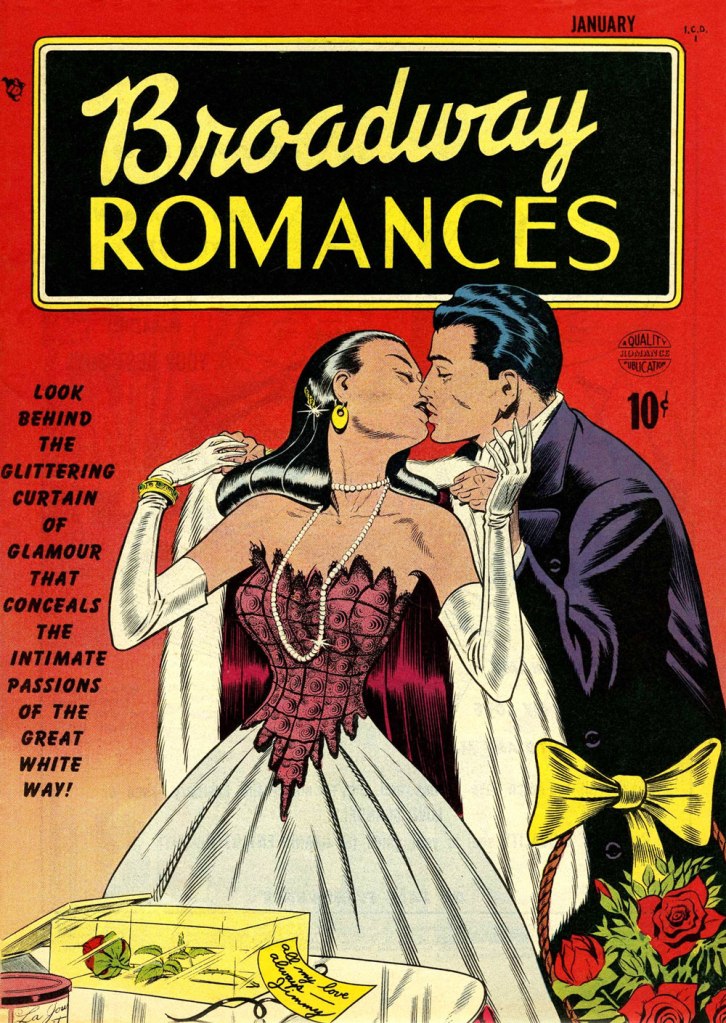

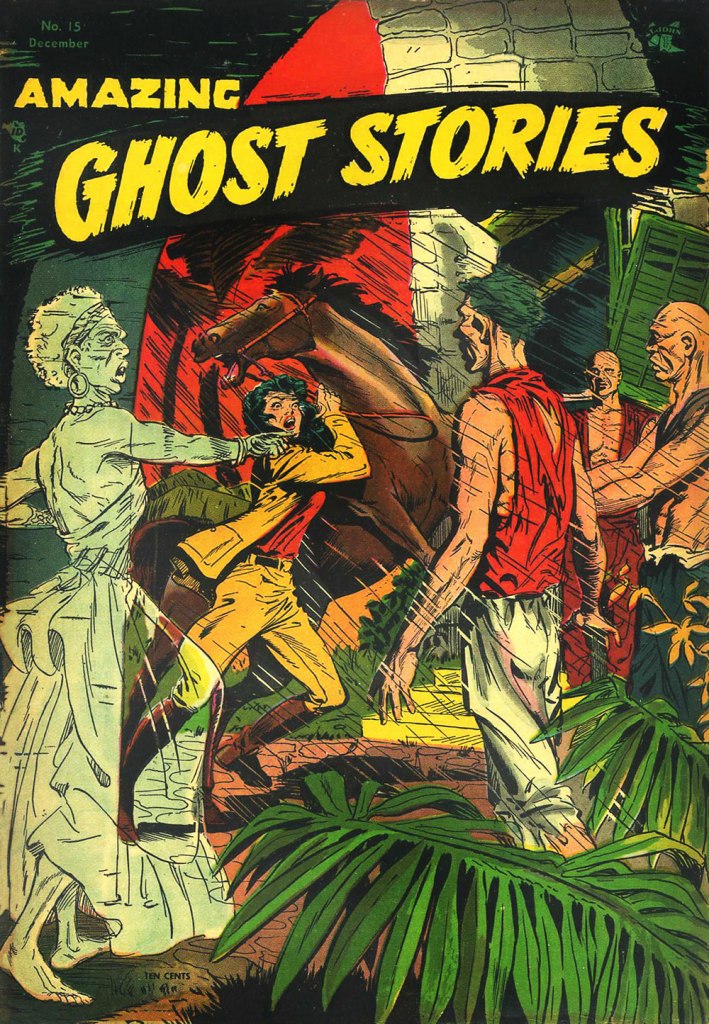

Kurt Schaffenberger had steady work at DC, but presumably — and understandably — sought to keep his options open, so he moonlighted for ACG, often under a pseudonym, probably unaware that the ‘competitor’ was covertly owned (at least in part) by DC co-founder and co-owner Harry Donenfeld. One can imagine Kurt’s distress when ACG folded in 1967. From what I can surmise, he did, in 1970, a lone, inexplicable cover for Stanley Morse… wildly outside his range but still kind of awesome. And then… he quietly boarded a bus to Riverdale.

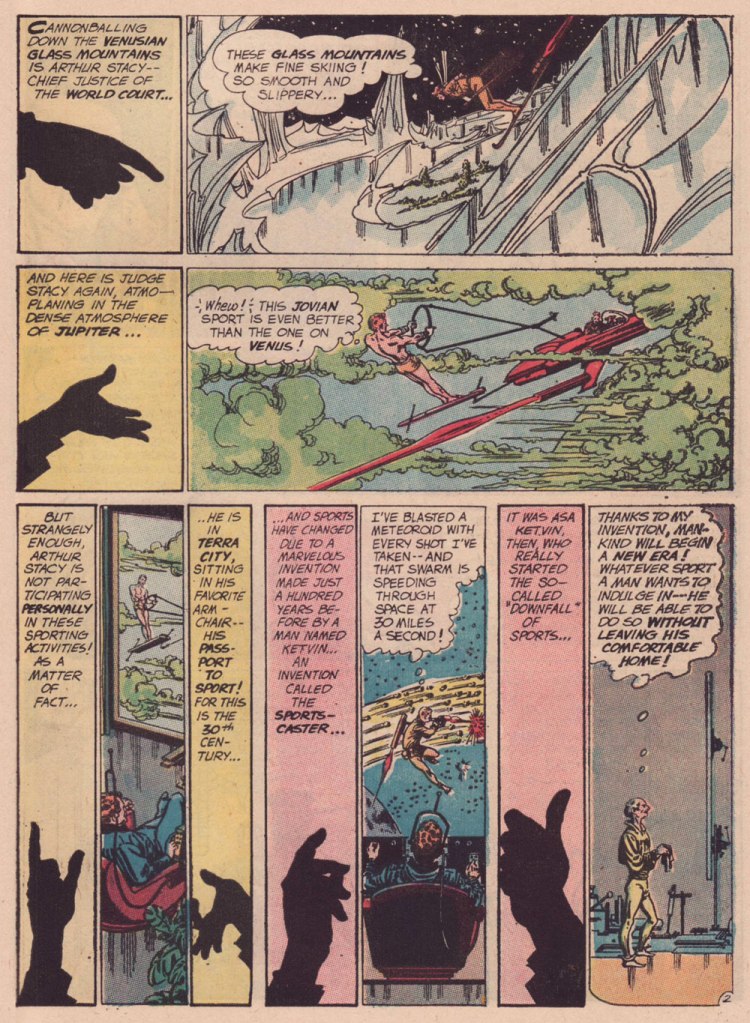

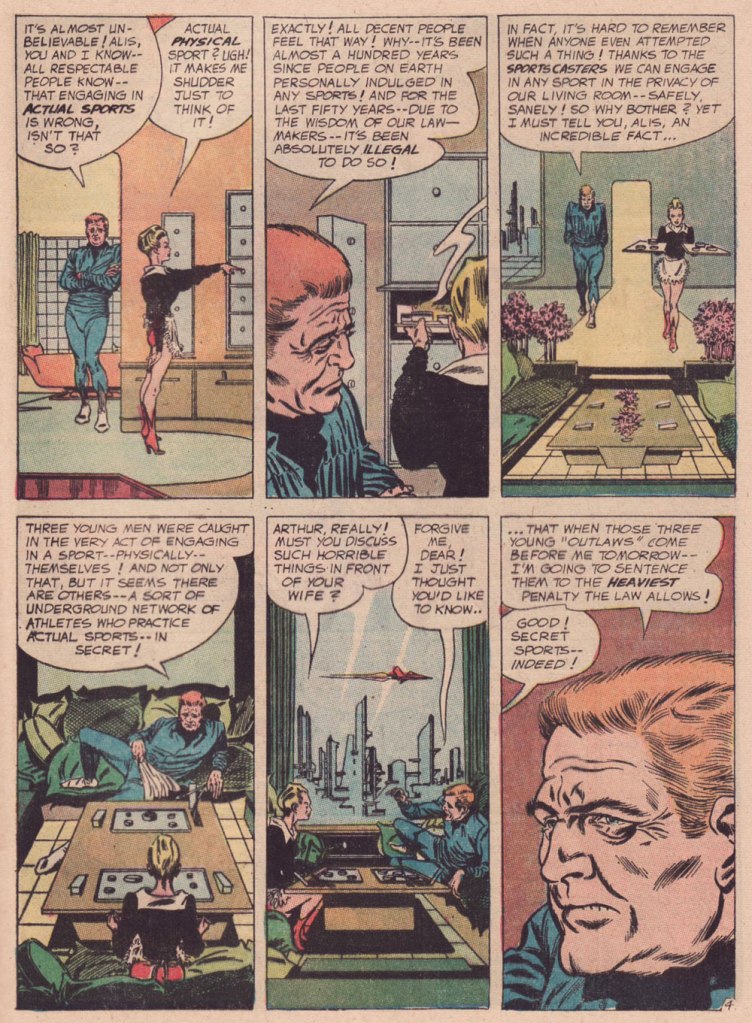

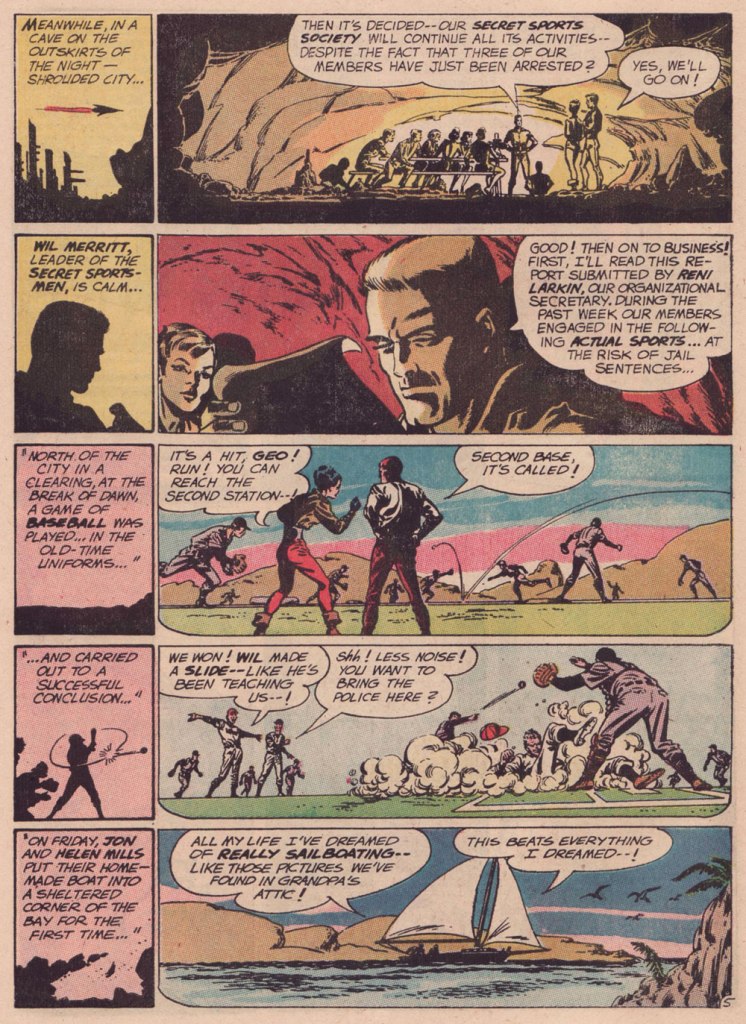

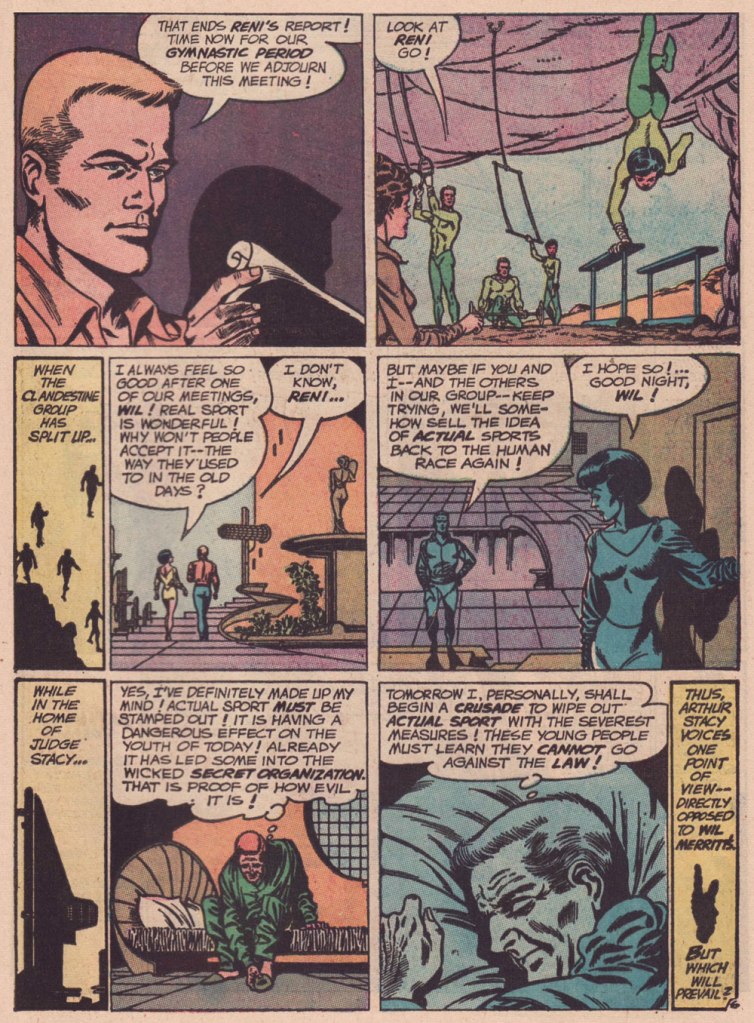

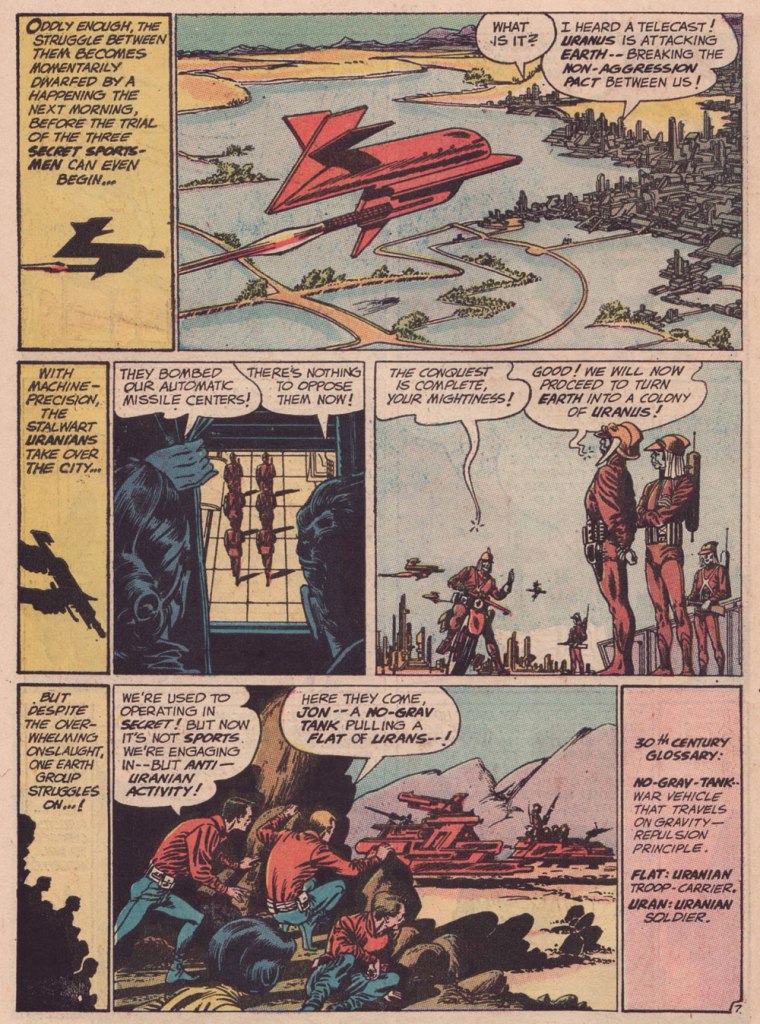

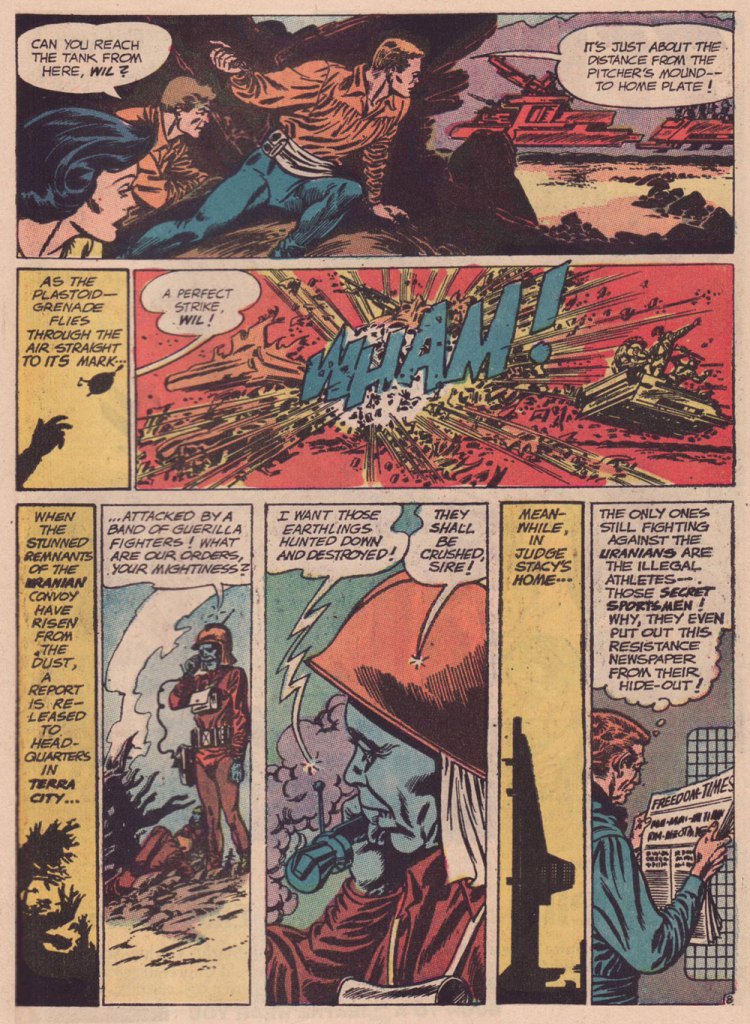

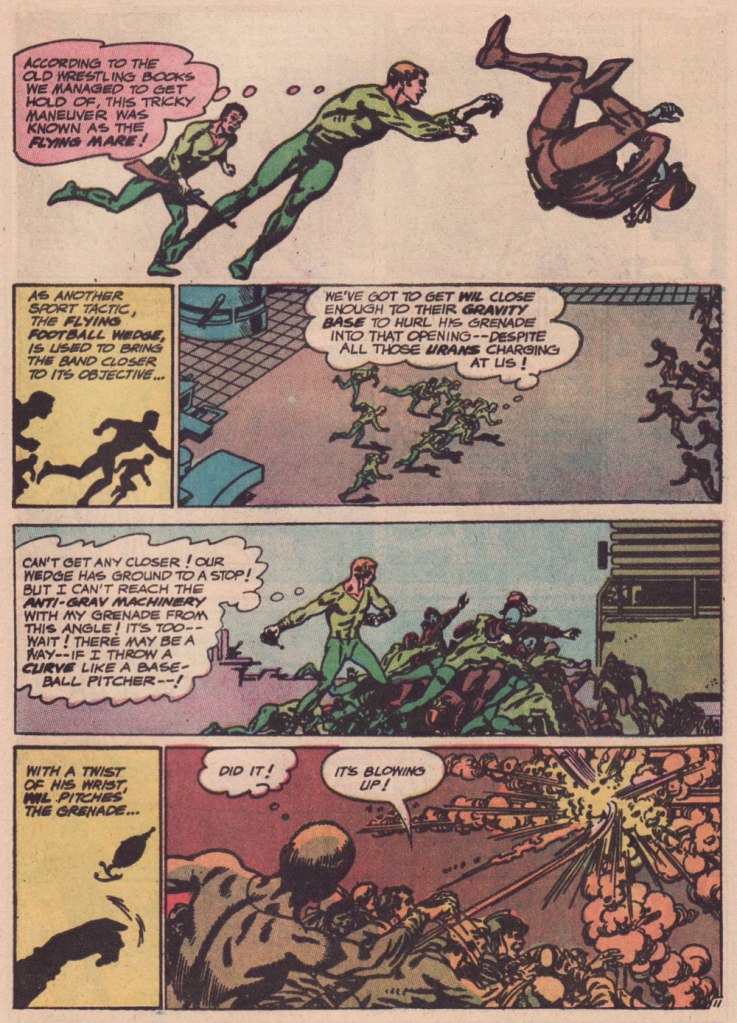

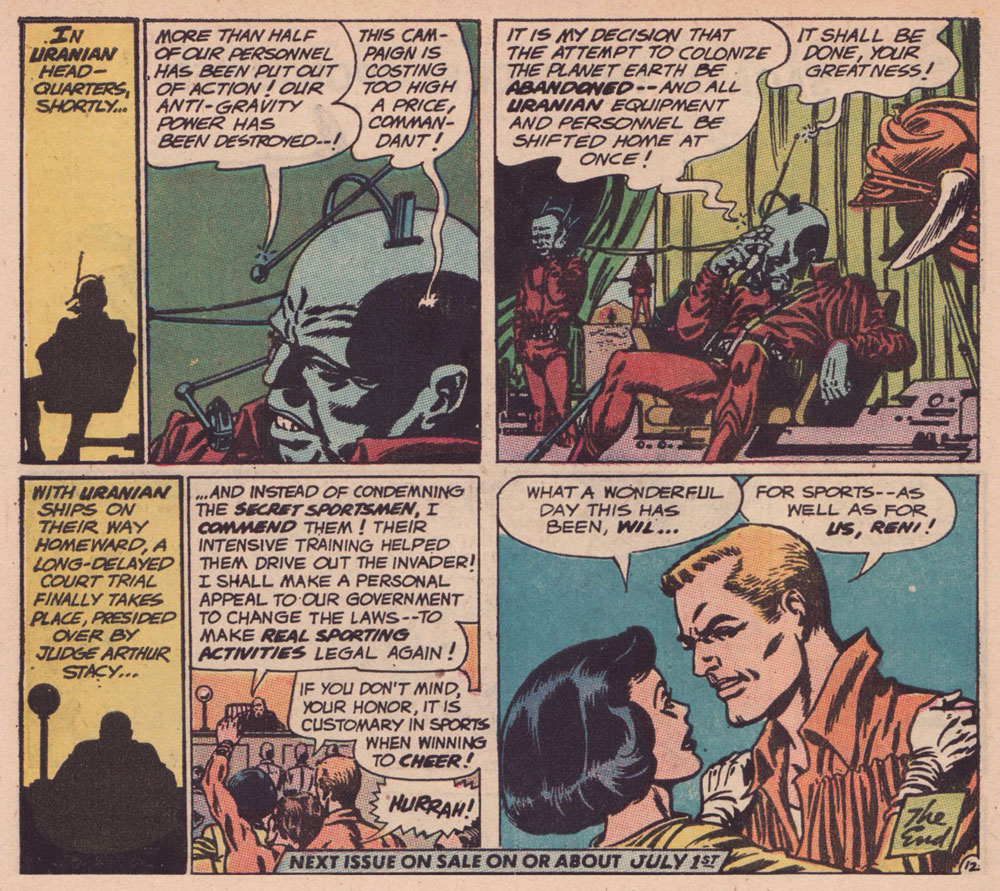

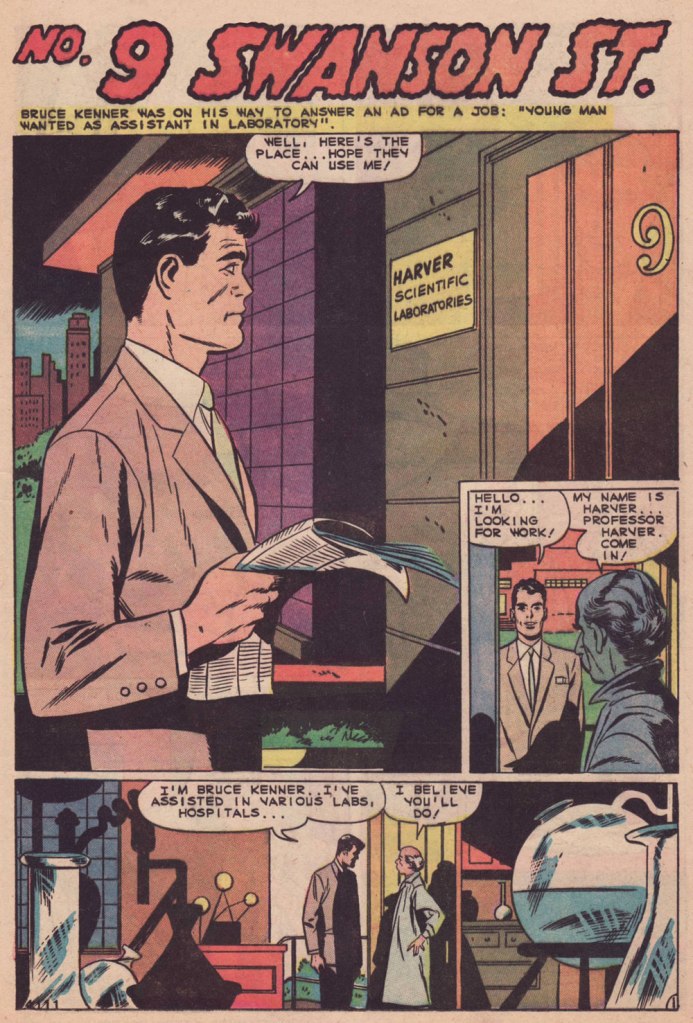

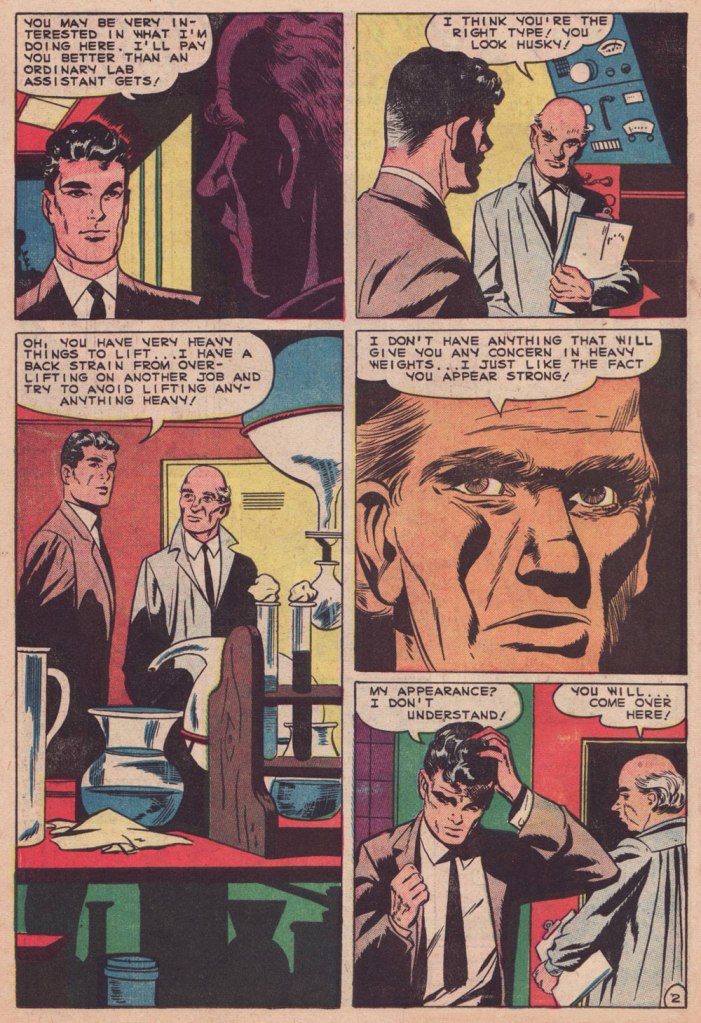

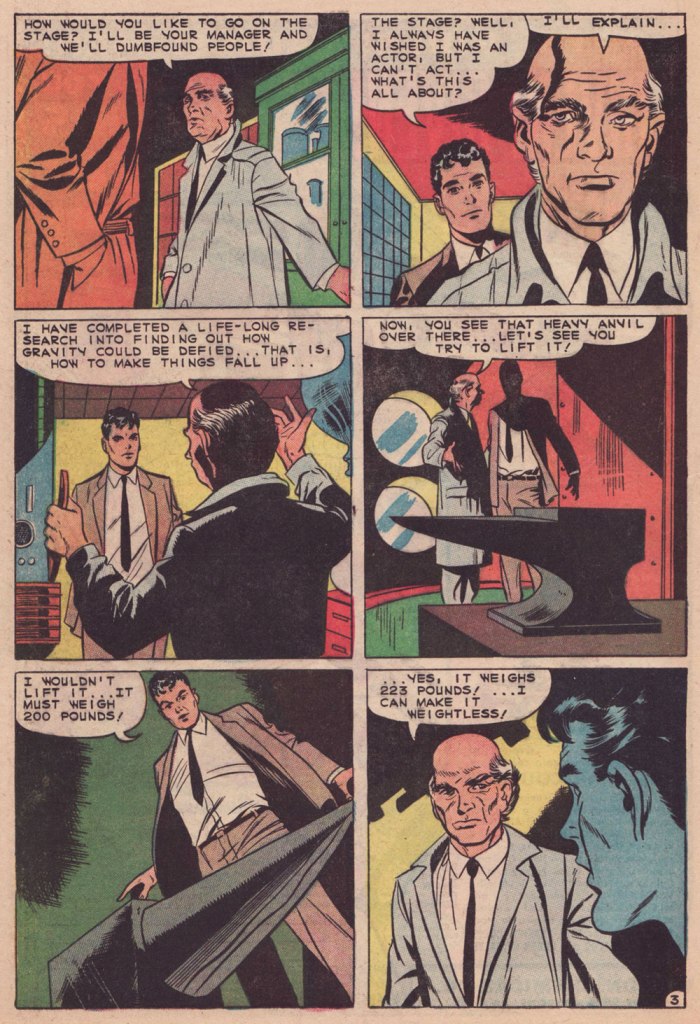

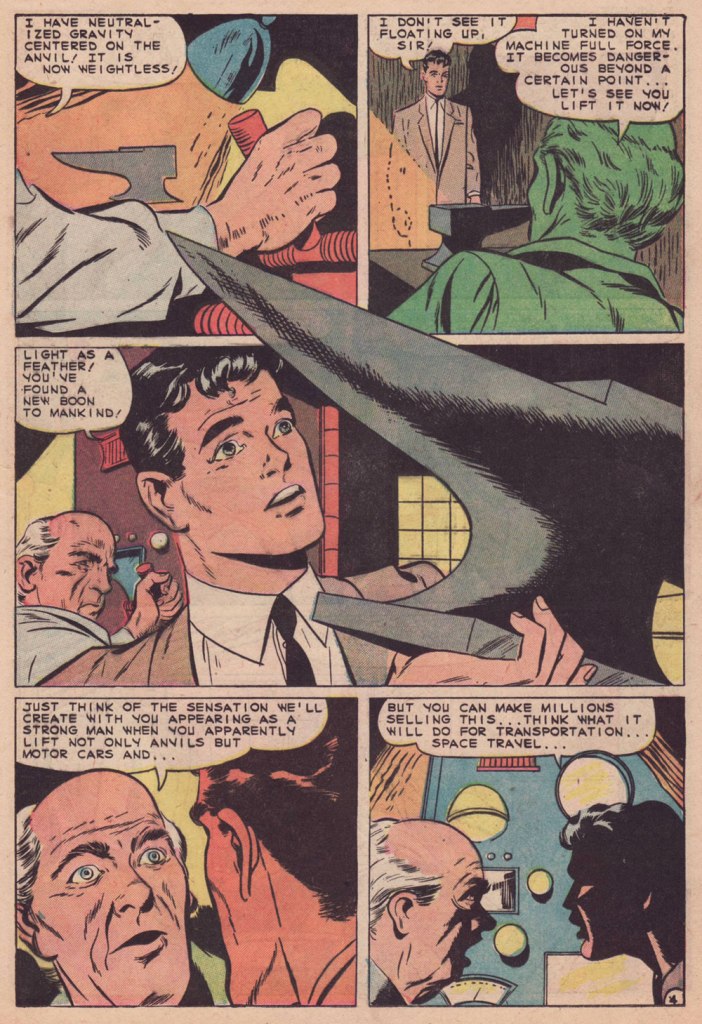

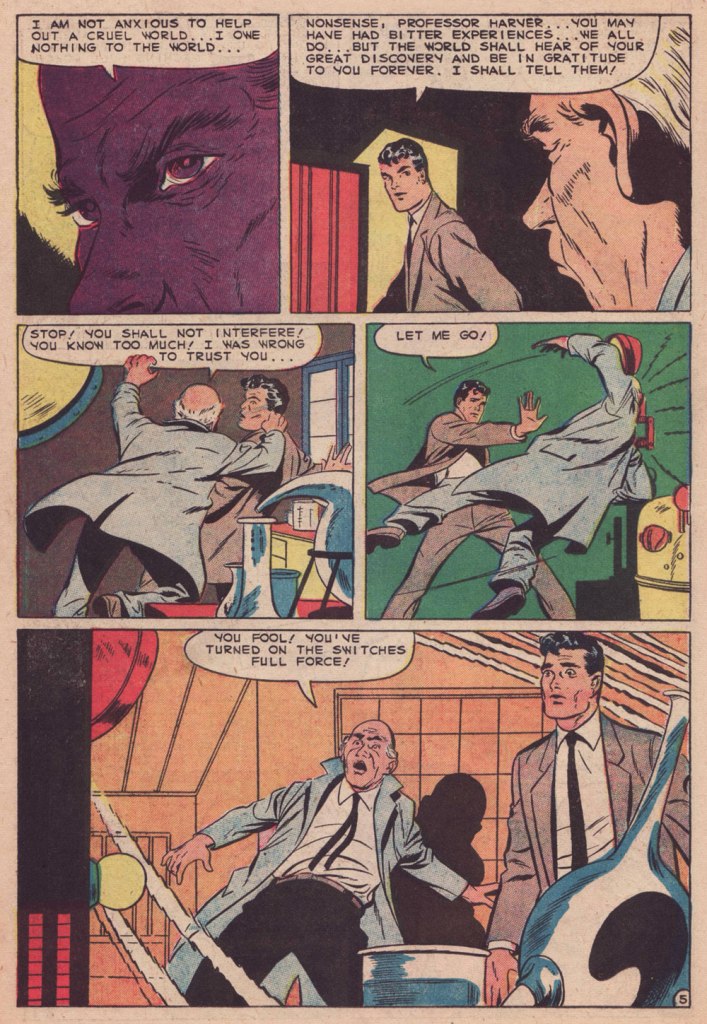

A couple more samples from Mr. Schaffenberger’s all-too-brief Archie period — solid, well-paced, ably-designed and economical storytelling:

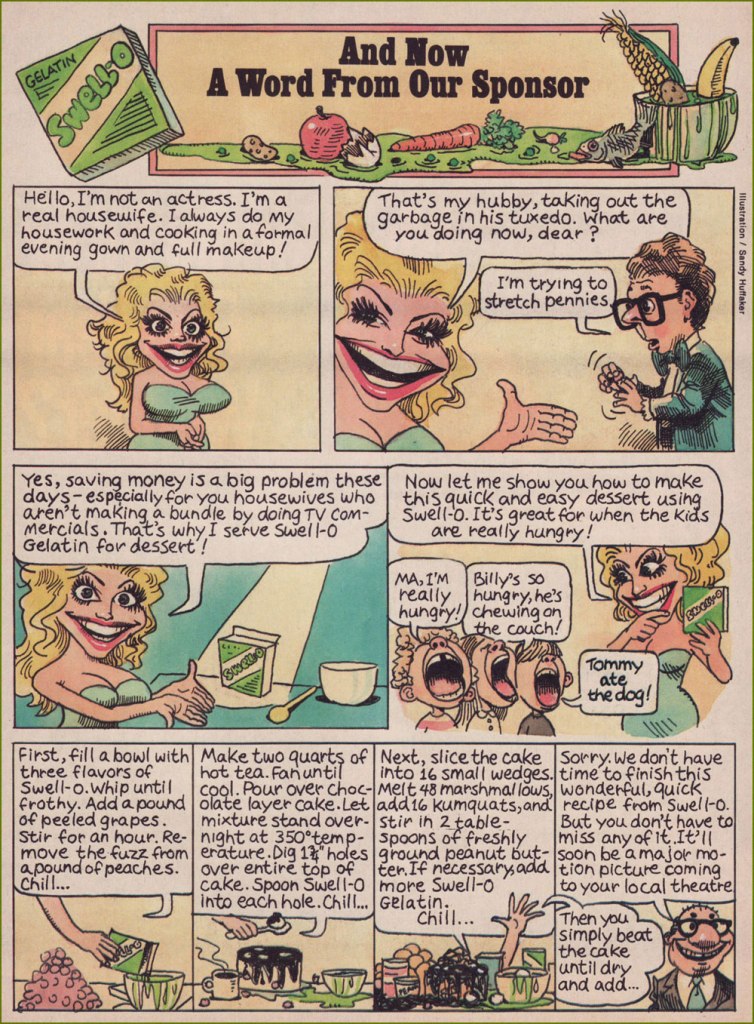

And then, there’s the case of Sal Amendola, a Neal Adams protégé whose reputation in comic books largely rests on a single Batman story, 1974’s ‘Night of the Stalker’, a highly praised tale whose chief conceits is that Batman never utters a word and weeps bitterly at the end. I’d apologise for the spoilers, but honestly, it’s been half a century, what mystery is there to dispel?

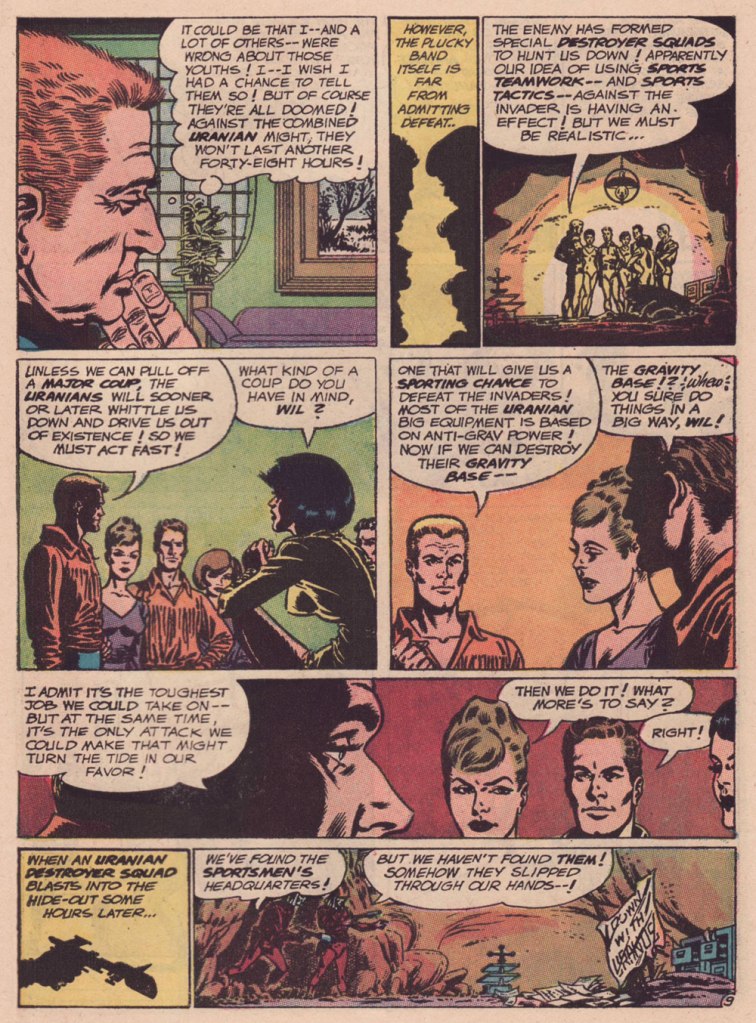

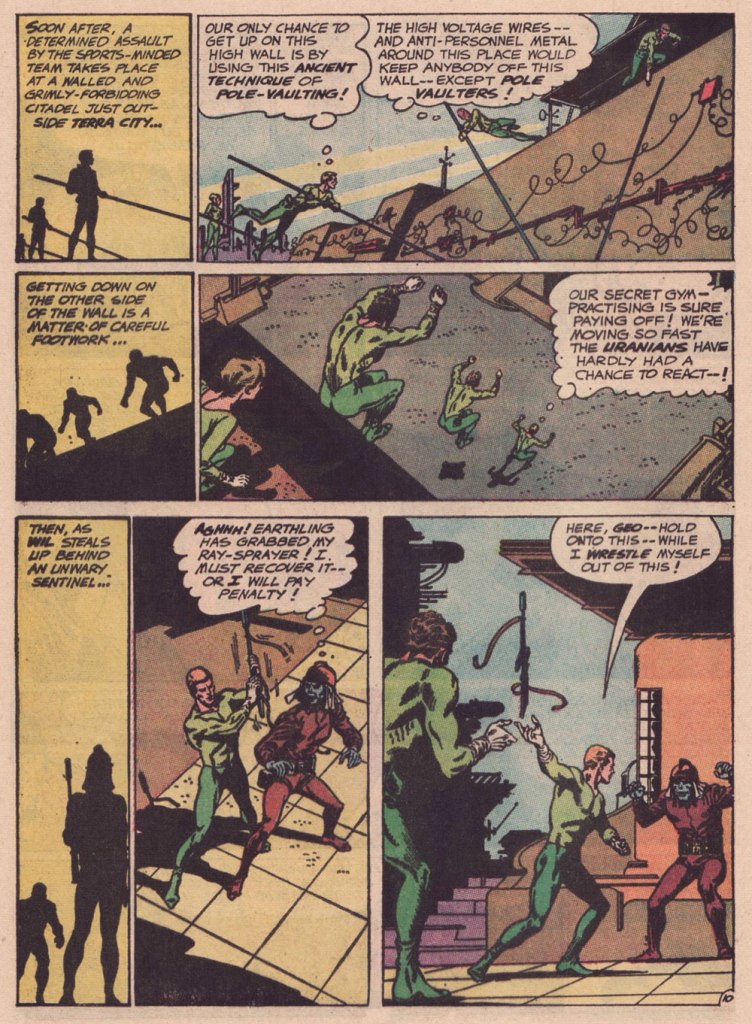

Anyway, after his turn in the Bat-spotlight and 1975’s Phoenix, one of the short-lived Atlas-Seaboard‘s more daring titles, Amendola turned up at… Archie. And it was not a good fit.

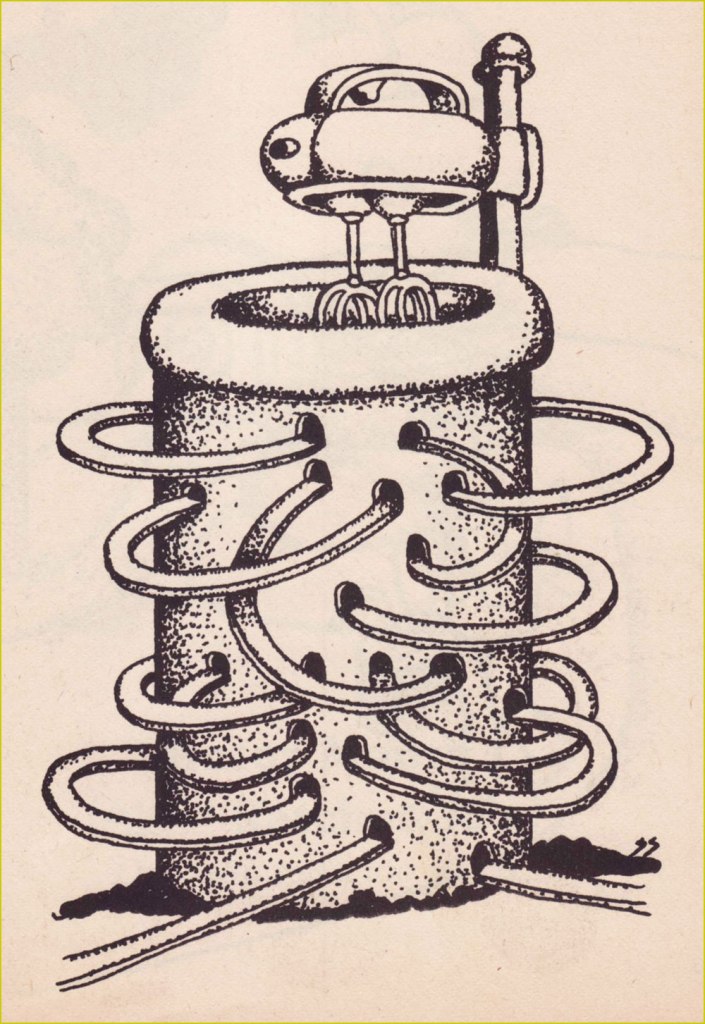

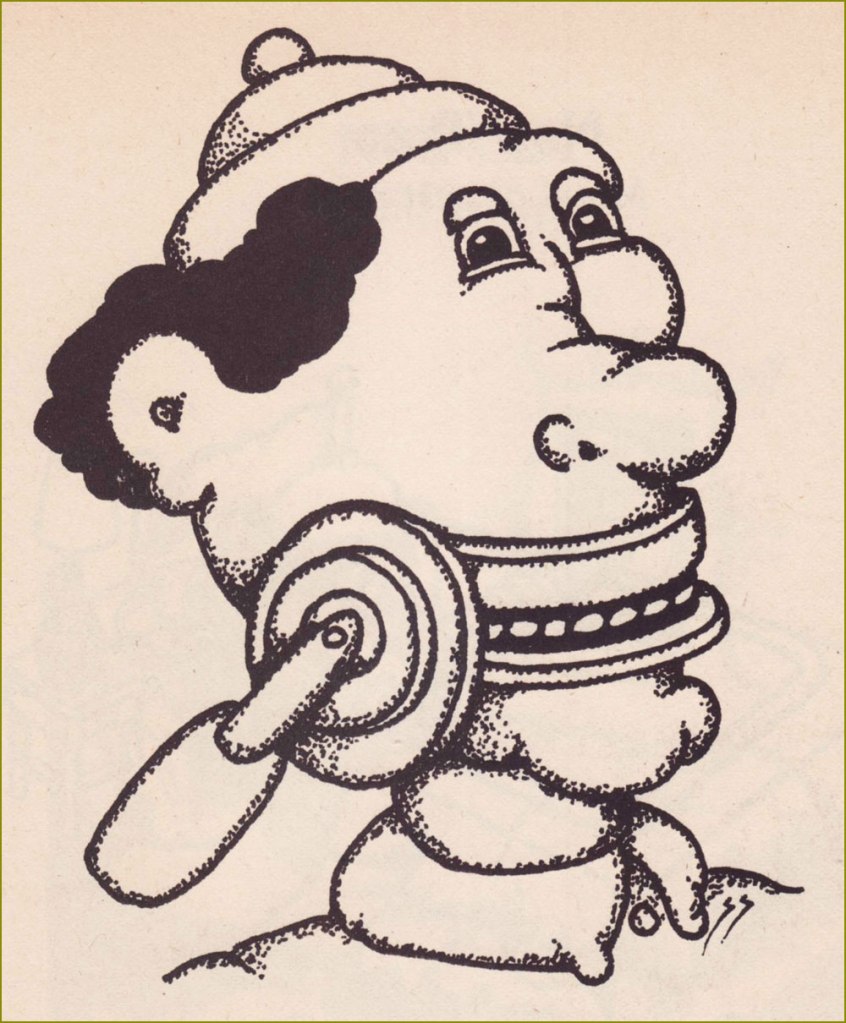

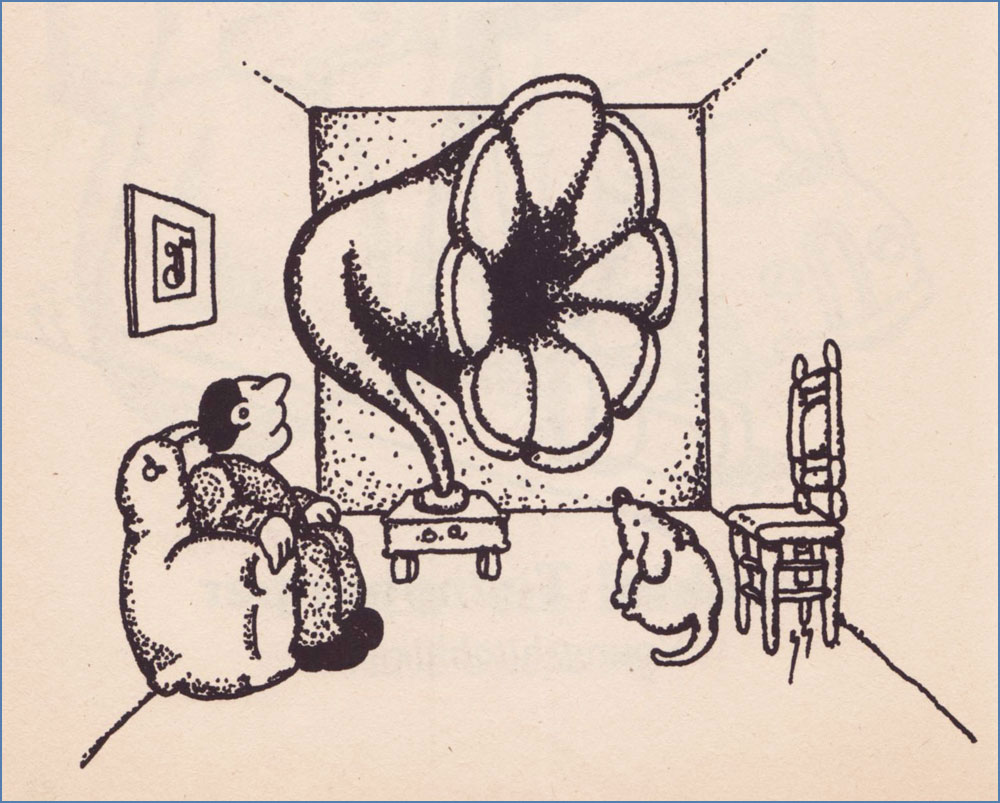

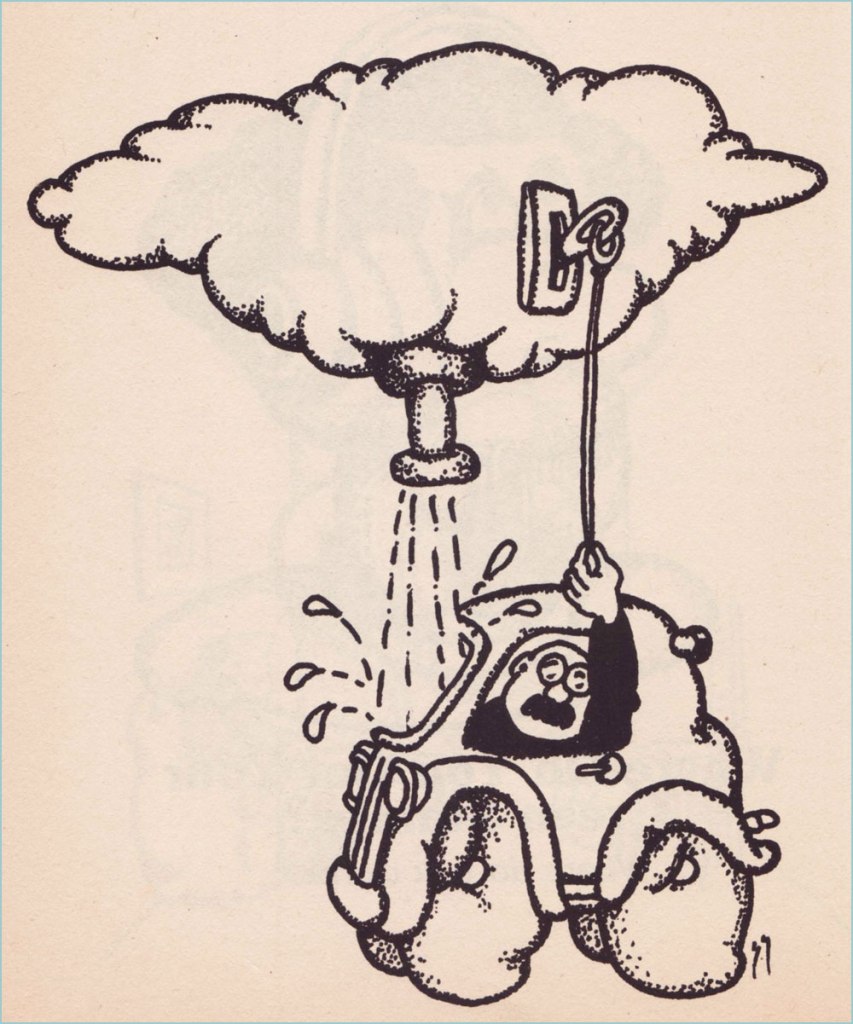

This, in fact, was the springboard for this post: a couple of years ago, I encountered an Archie story that so grotesquely missed the mark — stylistically speaking — that it bordered on the fascinating. You guessed it, Sal Amendola, utterly out of his element, not to mention, surprisingly… his depth.

Here are a pair of pages from Coach Reproach, published in Everything’s Archie no. 71 (Dec. 1978, Archie), script by George Gladir, pencils by Amendola, inks by Jon D’Agostino.

Schaffenberger’s fellow Golden Age veteran, Gene Colan, also found himself moonlighting in the 1960s. In his case, it was for Marvel, under the alias of ‘Adam Austin’, but also for Dell (just a couple of covers mid-decade) and more significantly for Warren Magazines. In the 1970s, he concentrated on Marvel and was, in the chaos that was the so-called ‘House of Ideas’ at the time, the single most reliable artist in the maelström: surely none can match his seventy consecutive — and meticulously detailed — issues of Tomb of Dracula, in addition to lengthy runs on Howard the Duck, Daredevil, Captain America, Doctor Strange and so forth.

Enter Jim Shooter, a man only Vinnie Colletta could love.

« When writer Jim Shooter became Marvel’s editor-in-chief in the late ‘70s, the tension between Colan and the younger authors came to a head. By 1980, Shooter and Colan were totally at odds with one another over Colan’s approach to storytelling. »

« [Shooter] was harassing the life out of me. I couldn’t make a living,” Colan said. “He frightened me, he really did. He upset me so bad I couldn’t function.” Just as she had urged Colan to quit one job [in] the 1960s, wife Adrienne begged him to leave Marvel in 1980. After delivering his resignation, Colan was asked to sit down and seek resolution with Shooter and publisher Mike Hobson. Colan agreed to the meeting, but declined any overtures to stay at Marvel. “Shooter was in the same room,” Colan recalled, “and I said, ‘That man’s not gonna change. He is what he is. Whether it’s six days, six months or six years, it’s not going to be any different, so I’m not going to put up with it for another minute.‘ » [ source ]

He then scampered over to DC for a few years. His production there was hit-and-miss, but his Batman run (1981-86) was outstanding, pairing him with some of the rare inkers who could do his nuanced pencils justice: Klaus Janson, Tony De Zuñiga (to my amazed delight!) and especially Alfredo Alcala.

But once his contract ran out, he was out knocking on doors again. Against all odds, Archie beckoned.

-RG