« The first hundred years are the hardest. » — Wilson Mizner

Having just learned this morning that today marks a century since the birth of André Franquin (1924-1997), I again pushed my planned post to the back burner. So, instead of writing about a celebrated Belgian genius, I’ll write about *another* celebrated Belgian genius.

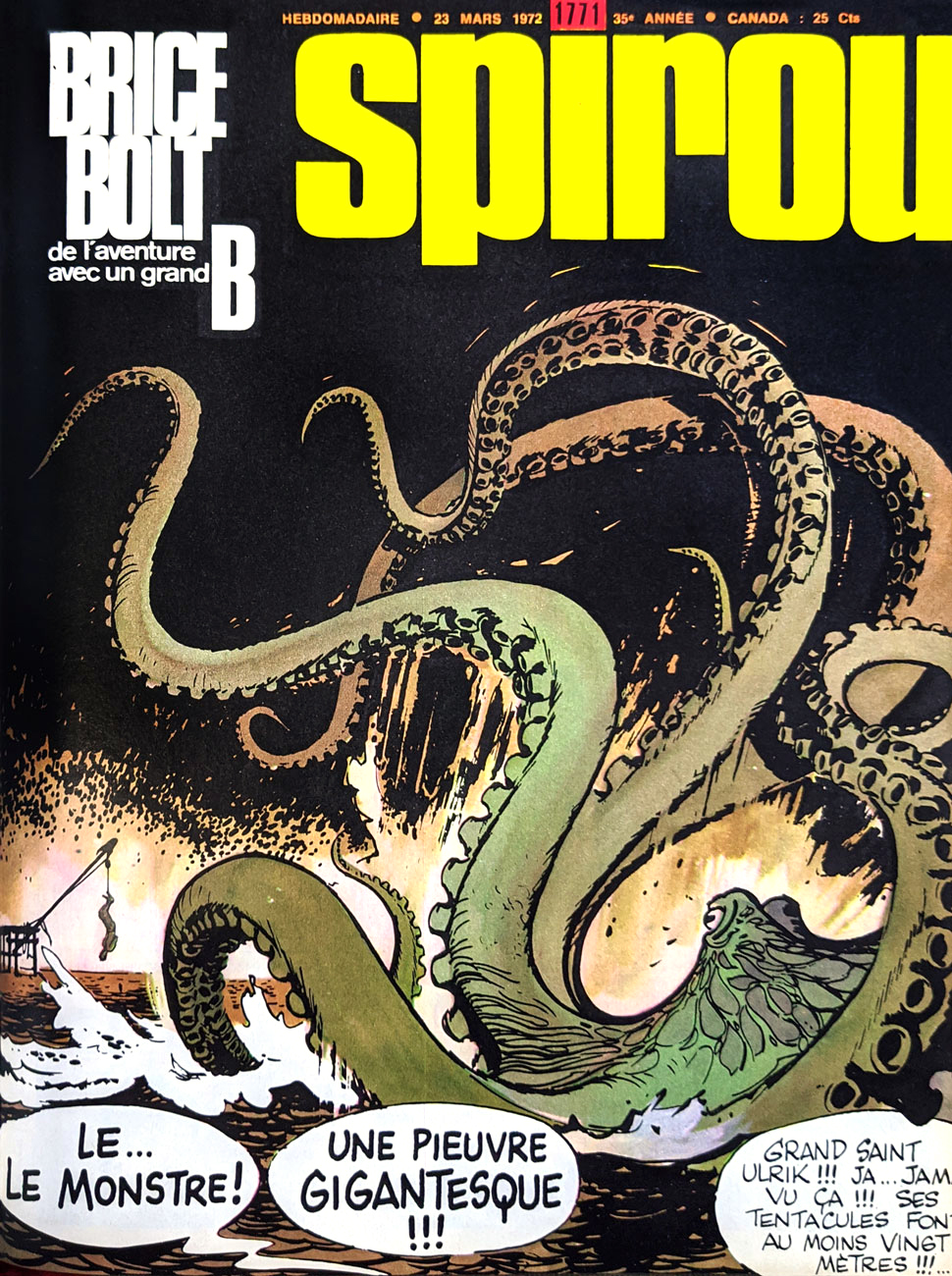

In 1977, a depressed yet inspired Franquin, suffocating within the confines of his much-imitated (at his publisher’s clueless insistence) style, created — with kindred confederate Yvan Delporte — Idées noires (Black, or perhaps more fittingly Bleak notions) as an outlet. It first appeared in the short-lived* Spirou mag supplement Trombone illustré, then moved to the more welcoming pages of Fluide glacial. An English-language edition, entitled Die Laughing, was published by Fantagraphics in 2018. Check it out here.

Here are a couple of Idées noires punchlines, which should give you an idea of their tone.

-RG

*These days, thinking about Gaston Lagaffe puts me in an ugly mood, I’m afraid. Franquin had expressly, and all along, requested that his creation be put to rest with him. But did his publisher – having built an empire upon Franquin’s creations — honour his wishes? No more than usual. Another arrogant slap — post-mortem this time — in the face of a genius exploited and mistreated his entire adult life. In this world, the interest of the characters… oops, pardon my French, ‘properties’ obviously trumps that of the flesh-and-blood creators. Every time. For there’s always some scab hack or other backstabber (and they *always* claim to be huuuge fans, as Miller said to Eisner, betraying him with a kiss) to aid and abet venal publishers. That’s how we got a pointless Sugar and Spike revival and all those Watchmen prequels. Hopefully, Monsieur Franquin’s daughter will prevail in her lawsuit against Dupuis to settle the matter in a just and fitting manner. [ Update: it didn’t end well. The suits won. ]

**« It is upon the publication of a Franquin article that the supplement is cancelled. In his piece, the fervently antimilitarist Franquin takes to task Thierry Martens, Spirou’s then editor-in-chief, for running articles about Nazi war plane models. » (translated quote from L’histoire de la bande dessinée pour les débutants by Frédéric Duprat, p. 131, Jan. 2011)