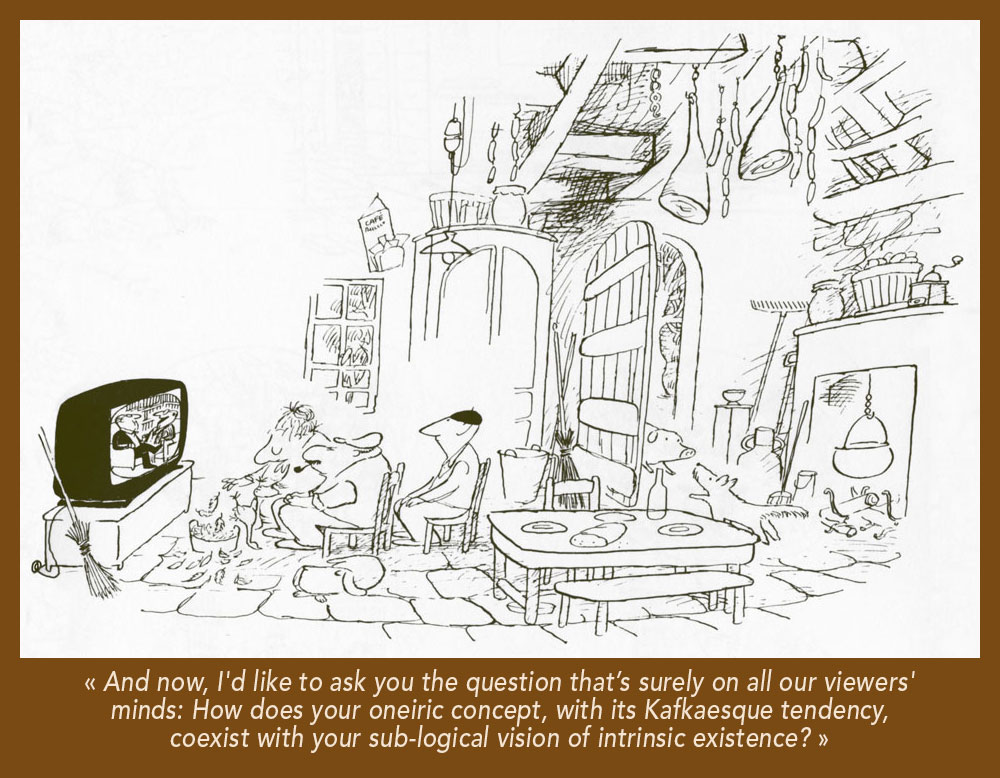

« In man’s struggle against the world, bet on the world. » – Franz Kafka

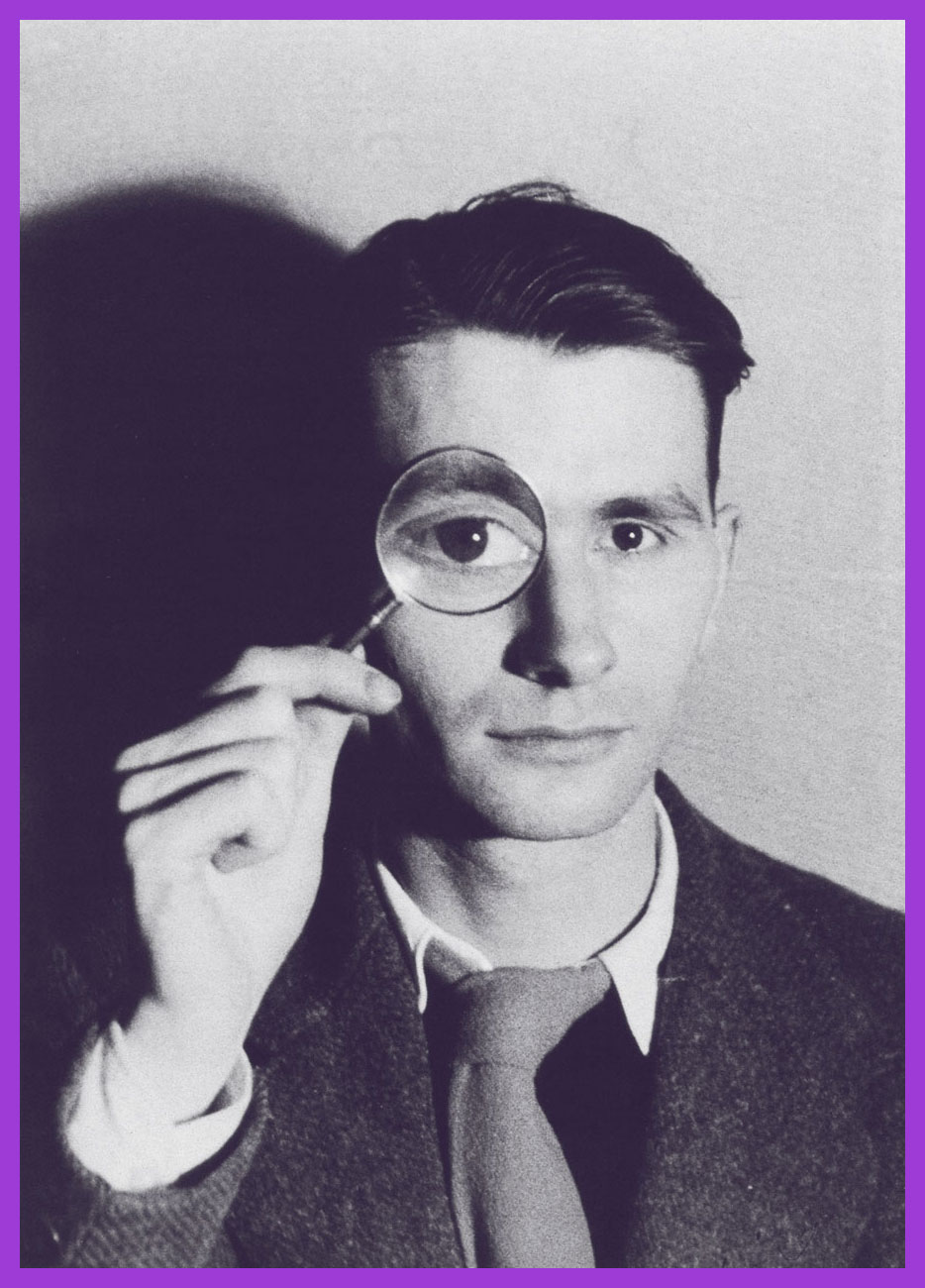

Time for another entry in our leisurely, unsystematic and subjective survey of Europe’s most significant panel cartoonists. Today, we examine the life and work of Jean-Maurice Bosc (1924-1973).

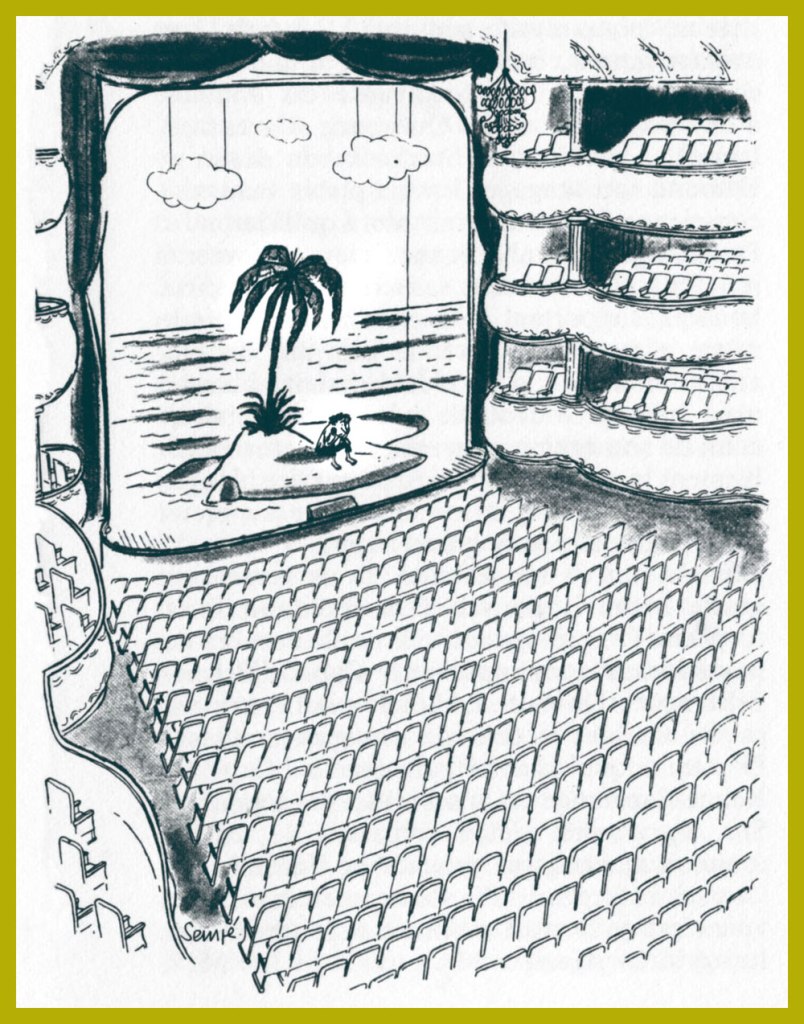

His is a familiar story: guy goes to war, comes home changed (likely suffering from what was once called ‘shell shock’, then ‘battle fatigue’, and nowadays ‘post-traumatic stress disorder’ — “burying the pain under jargon“, as George Carlin put it), can’t return to old routine in the family vineyard, tries other tacks, decides on drawing; looks for gainful employment, starting at the very top, miraculously gets in. Thrives for several years, producing well over 3000 drawings, seeing print in countless magazines all over the globe. Then it turns sour.

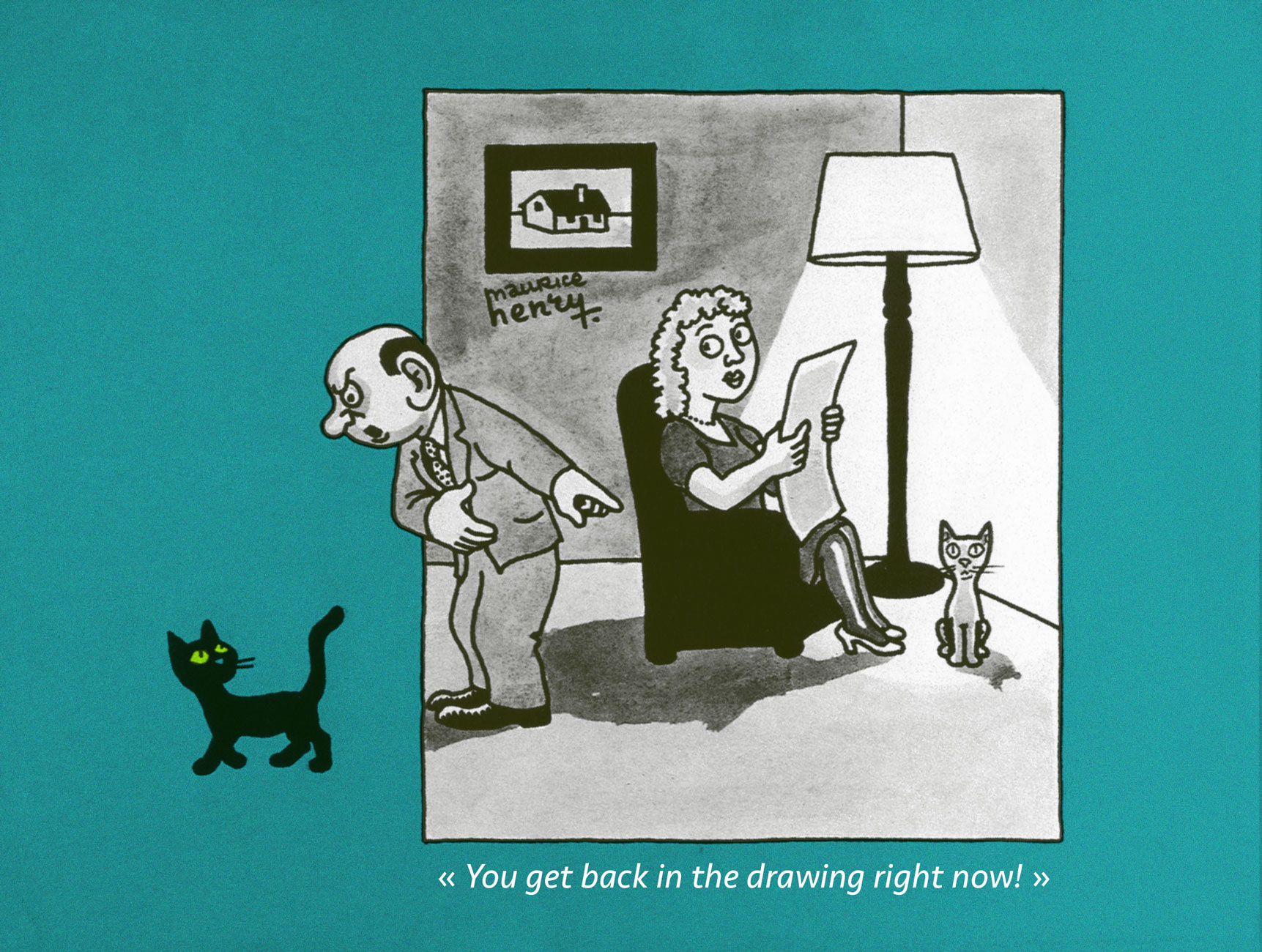

Jacques Sternberg wrote, in Les chefs-d’œuvre du dessin d’humour (1968, Éditions Planète):

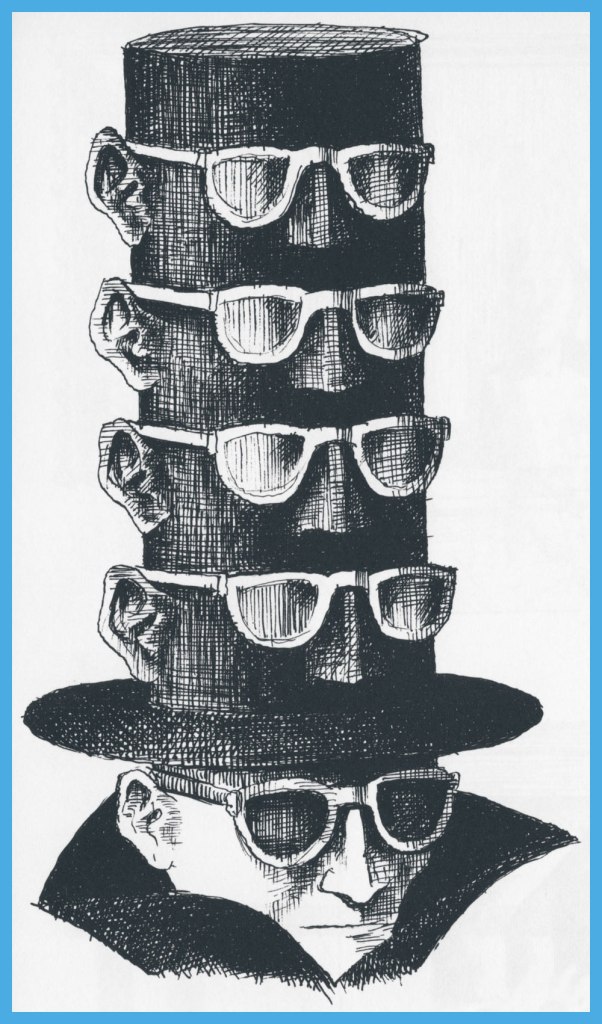

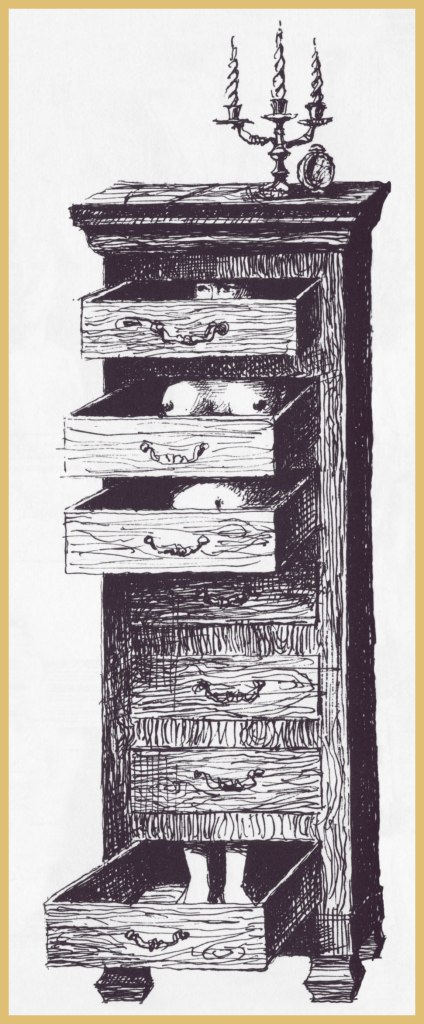

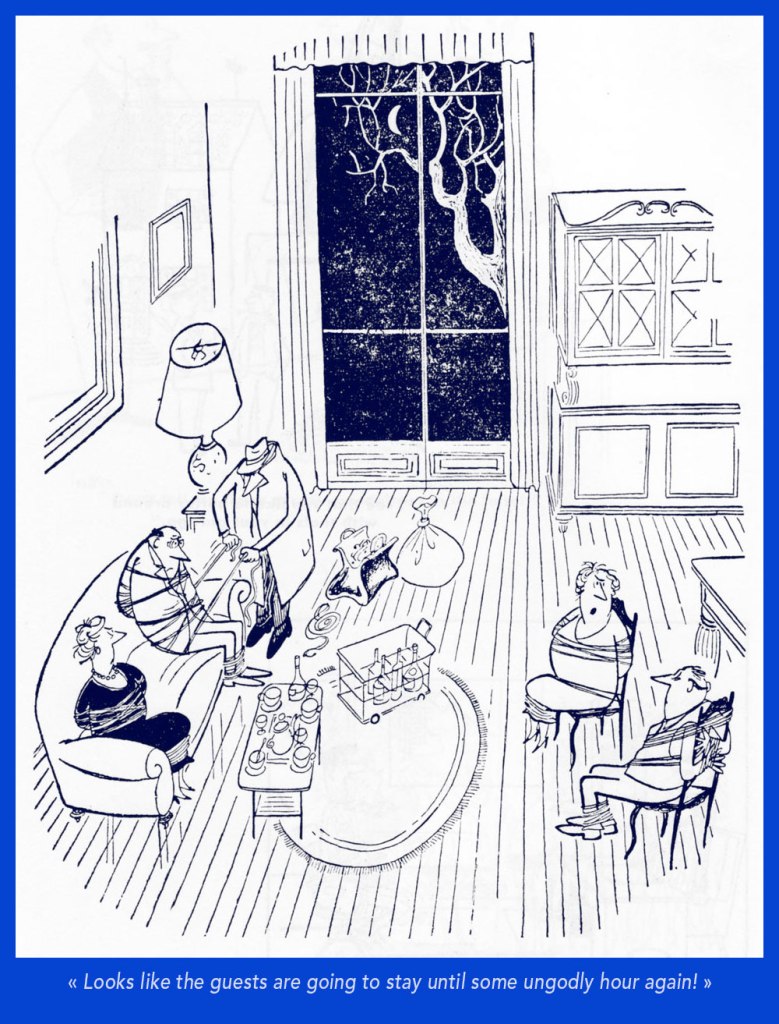

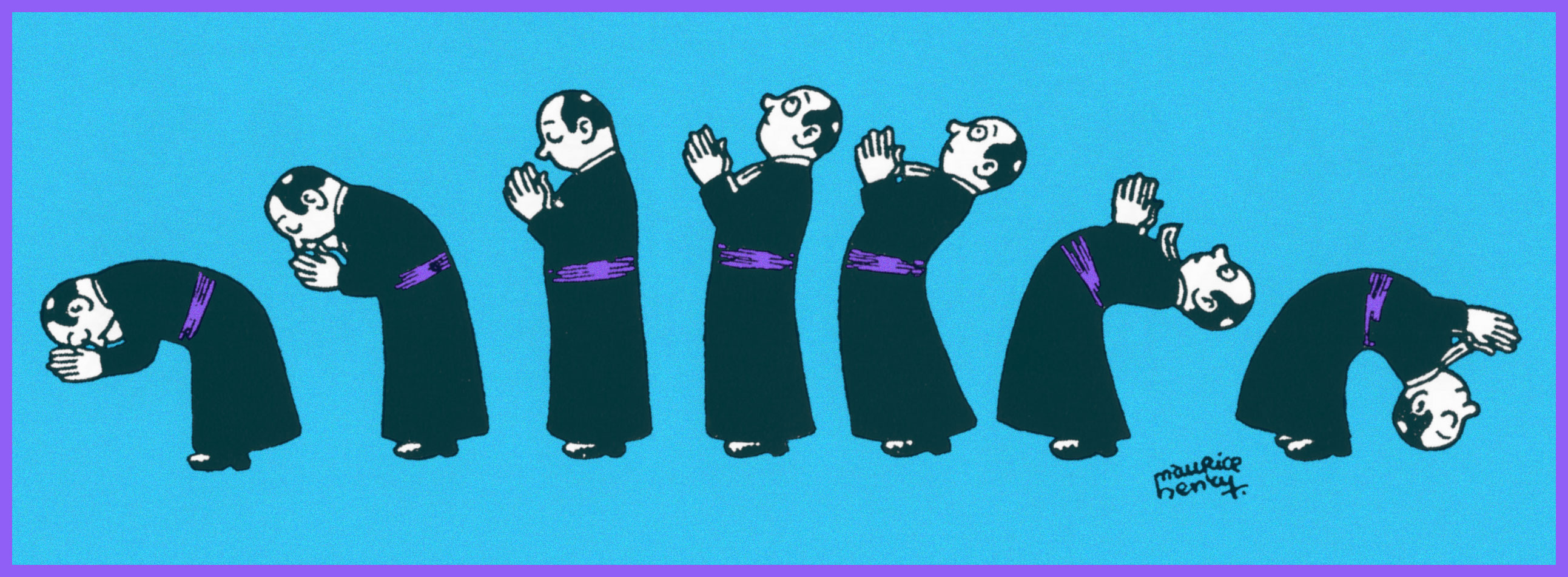

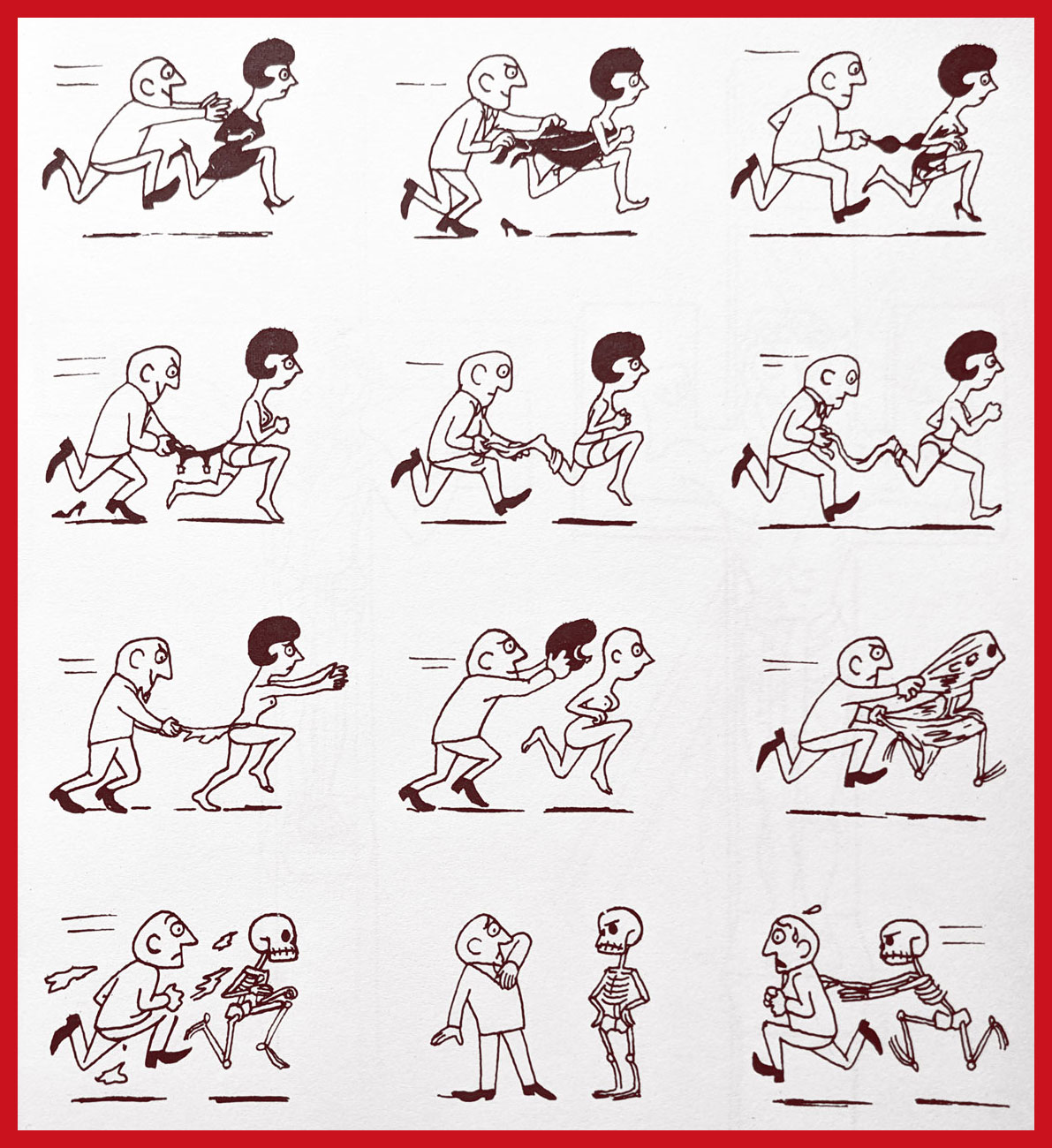

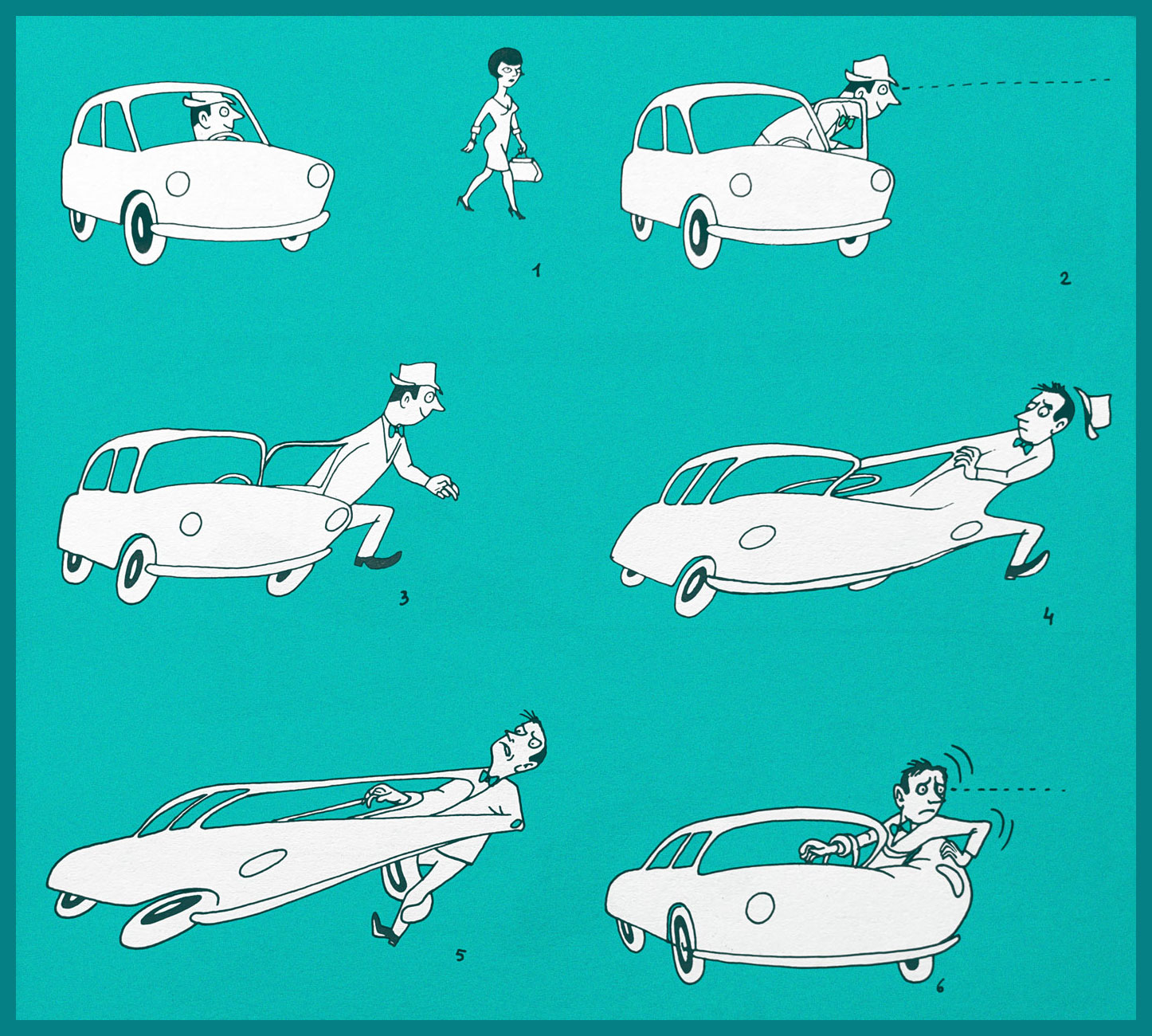

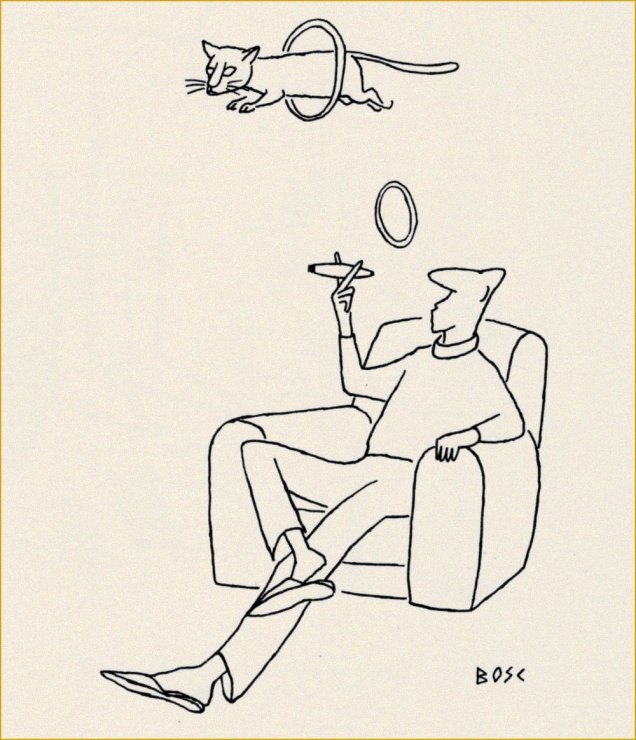

« Returned in a highly weakened state from Over There, Bosc, resigned to forced rest, began to draw after falling in love with the drawings of Mose and Chaval. Over a few months, he produced hundreds of drawings, giving the humorous arts, without even realising it, a most singular starkness, a particular line that belongs quite exclusively to Bosc, though it’s been much and often mimicked since.

It was in 1952 that Bosc went up to Paris. Eight days later, a stroke of luck: he lands a whole page in Paris Match, which was to turn him into one of the magazine’s stars. »

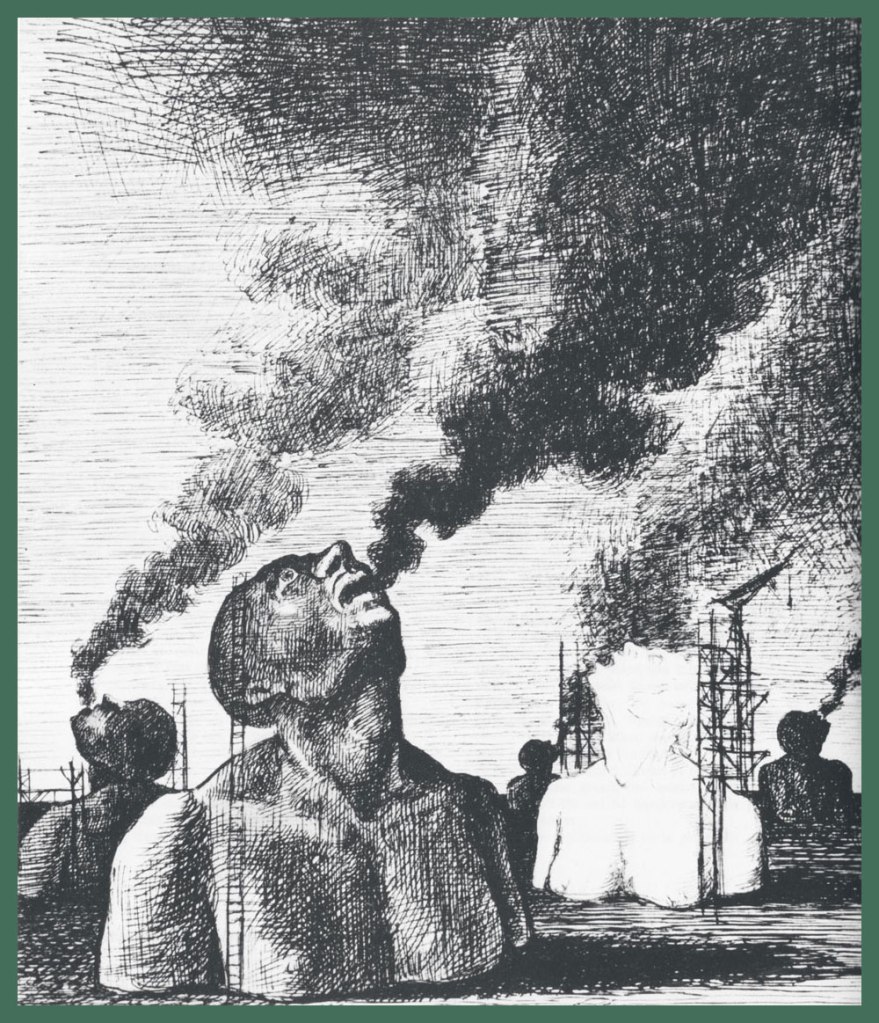

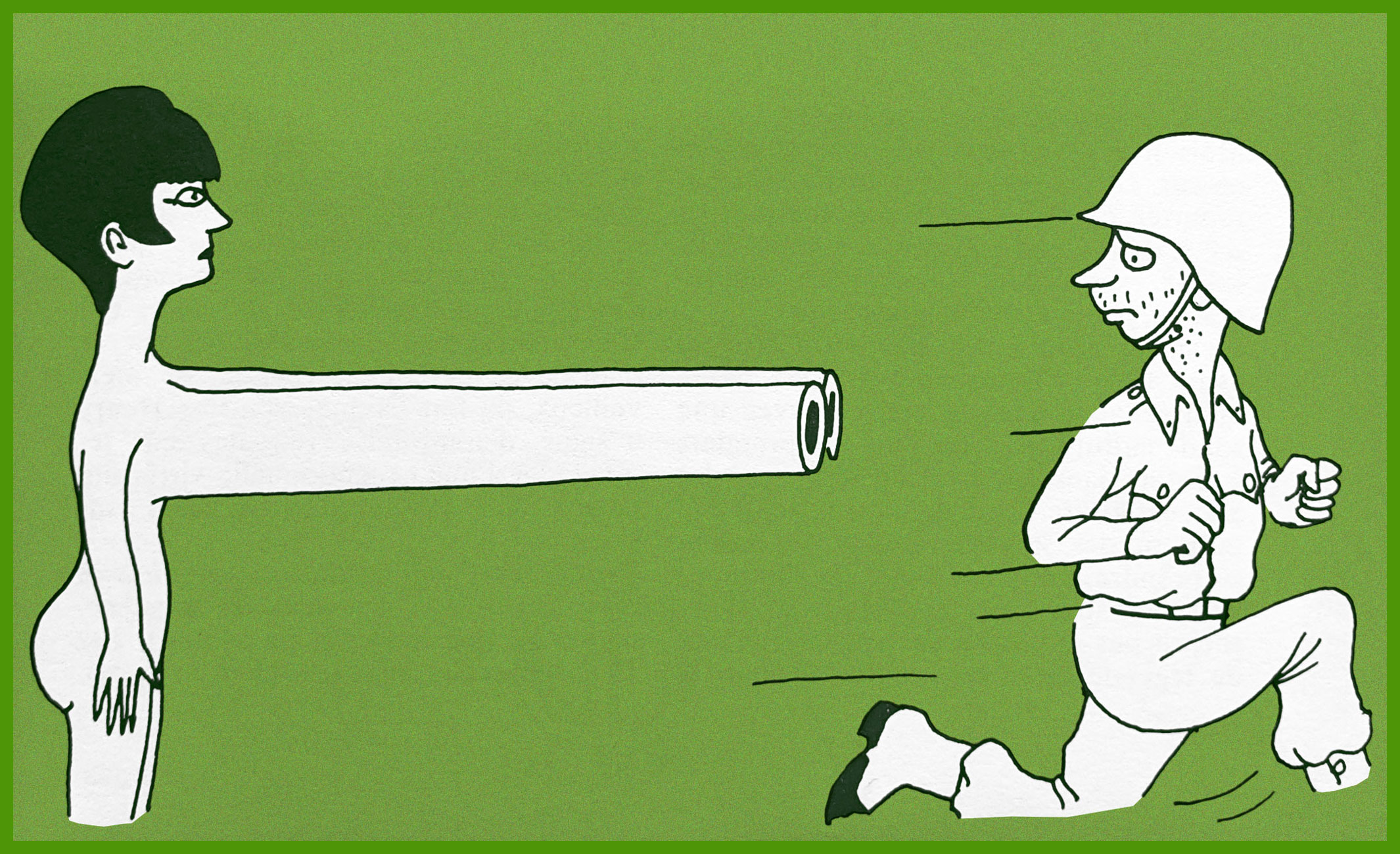

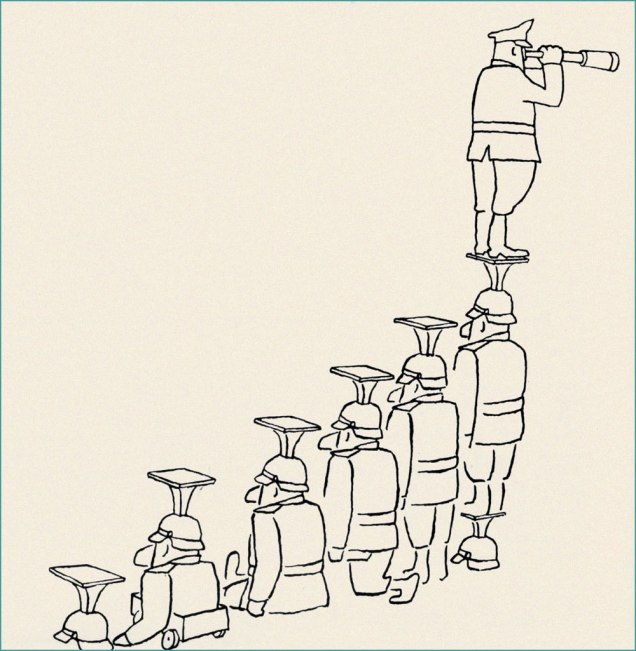

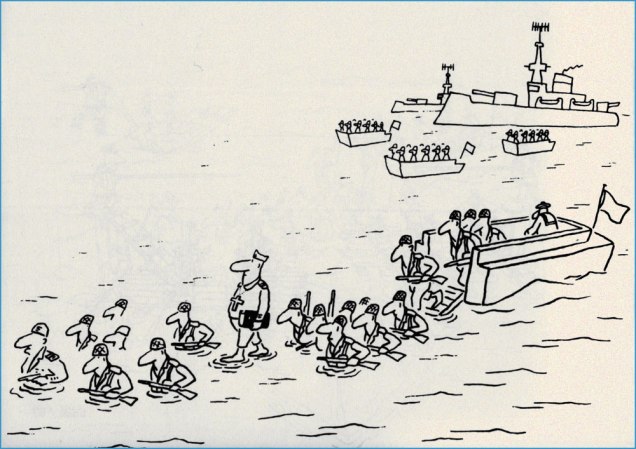

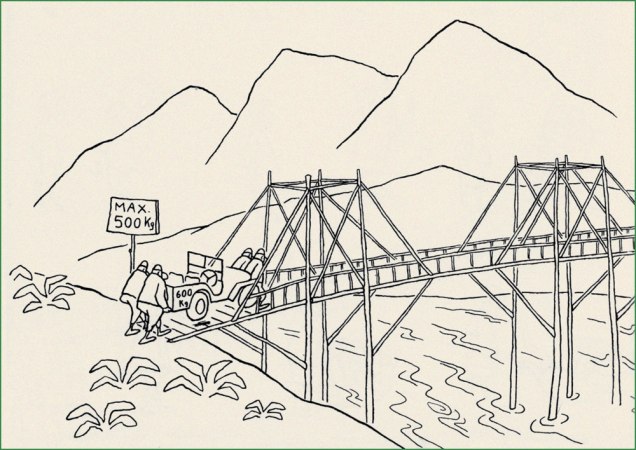

« After spending three years mindlessly obeying orders, two of which in the Vietnamese jungle, Bosc was severely traumatized. “After what I’ve witnessed in Indo-China“, he wrote, “I could no longer eat or sleep, ever.” He later told his sister that he had shot dozens of fellow soldiers, saw gruesome fights and, while imprisoned, heard prisoners being tortured. She recalled that he could no longer stand loud noises and got furious whenever she wanted to kill a mere spider. Bosc became a lifelong opponent of war and militarism. »

Also, he was right: one shouldn’t kill spiders.

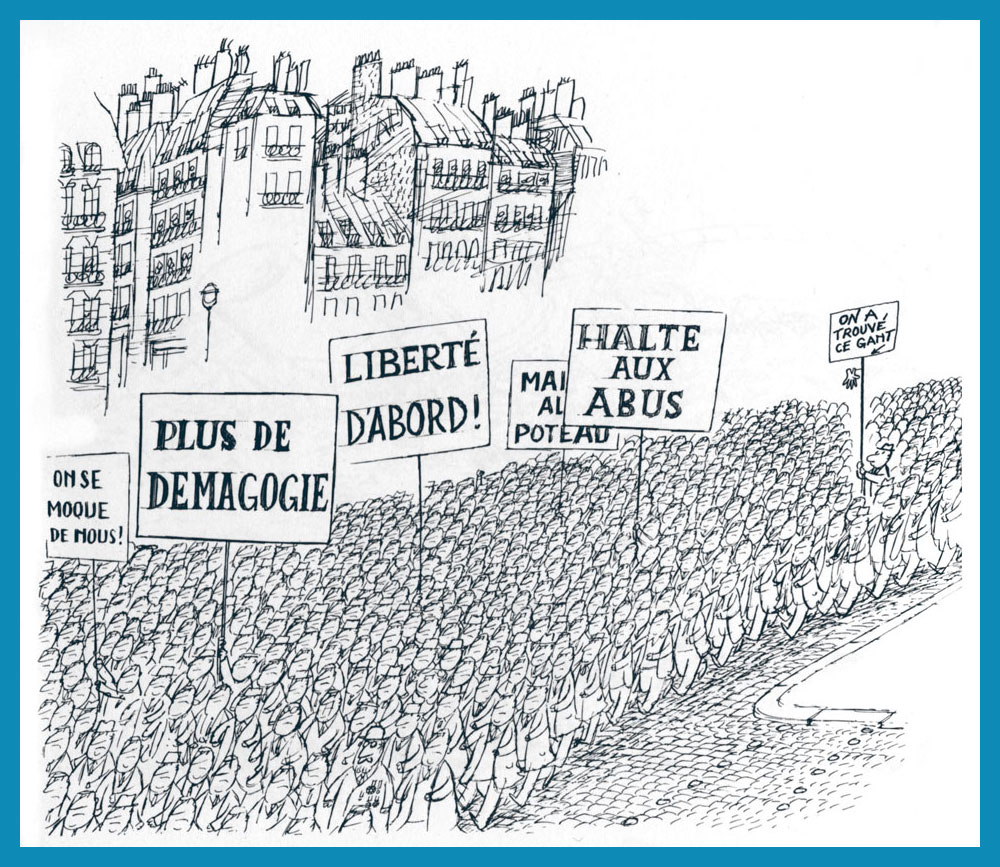

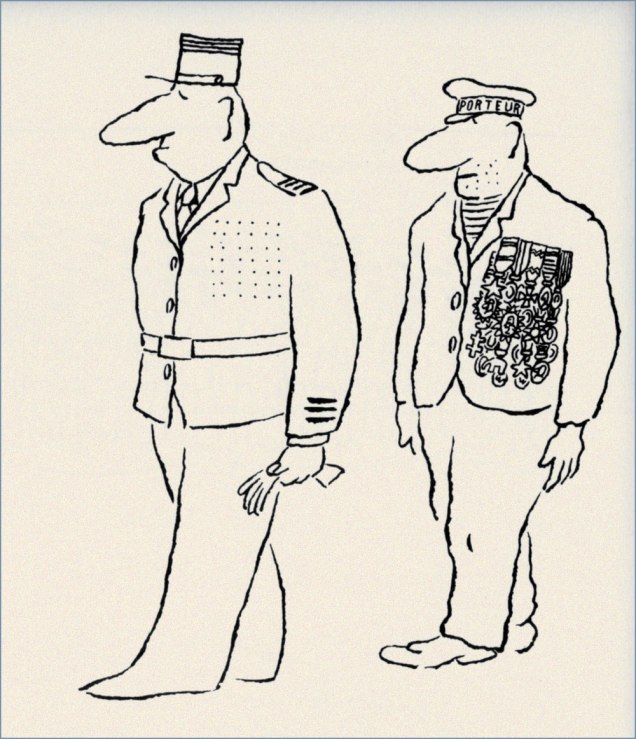

Like most of his friends and colleagues, « … Bosc had lived through the Nazi occupation in World War II. After the Liberation, he felt disgusted by his country’s attempts to keep subjugating their overseas colonies to similar oppression and exploitation. President Charles de Gaulle was the sum of everything they hated: a conservative politician who didn’t agree with the growing sentiment of anti-colonialism, the sexual revolution and disregard for Church, army and family values. Bosc often ridiculed De Gaulle in his work. Once, the cartoonist was fined 3,000 francs, with a month’s probation, for daring to mock the army in a magazine. Bosc’s work revealed he had no respect for politicians. Interviewed by Paris Match in 1965, Bosc claimed that Alexander the Great was his “favorite great statesman, since he died at age 33.” » [ source ]

I won’t gloss over the tragedy of his final years:

« Tragedy struck in 1968, when his good friend and colleague Chaval committed suicide. In June 1969, Bosc had a mental breakdown and was hospitalized. Suffering from an illness depigmenting his skin, he weakened more and more, often to the point of no longer being able to stand on his own two feet. He went in and out of clinics, even tried electroshock therapy, but nothing helped. As his health deteriorated, so did his mood. From 1970 on, he basically quit drawing cartoons. In 1973, the depressed cartoonist went to his garage and shot himself. He was 48 years old. »

Despite his having left us over half a century ago, Bosc is remarkably well-remembered. His Lambiek biography, written by Belgian cartoonist Kjell Knudde, is richly detailed and informative. His official website, hosted by Bosc’s devoted nieces and nephews, is a marvel of commemoration.

-RG

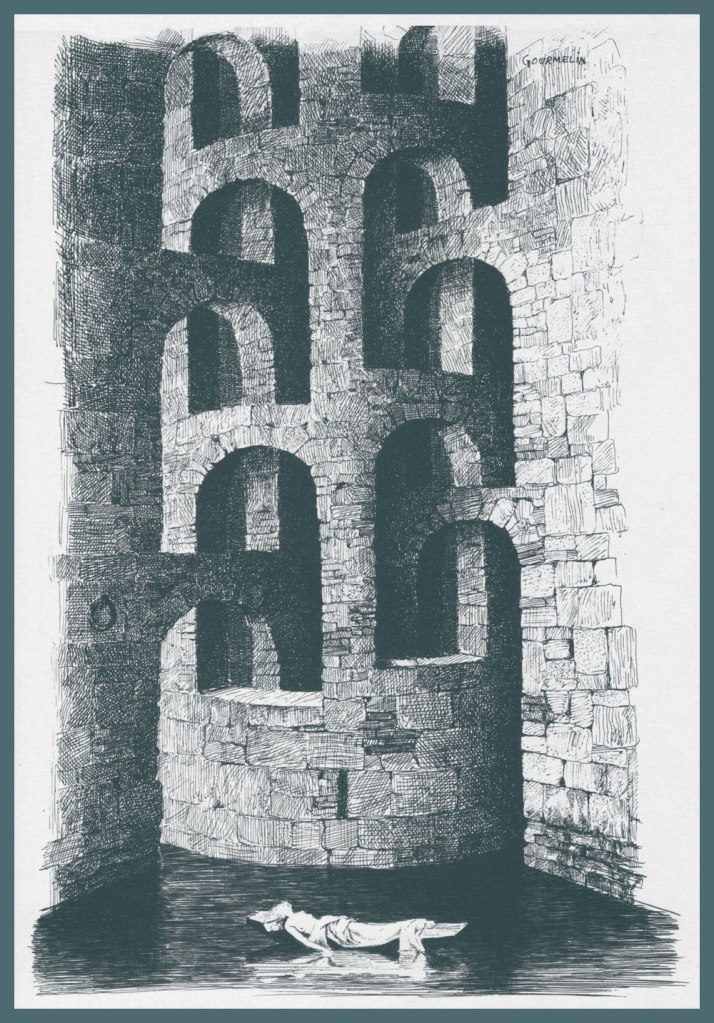

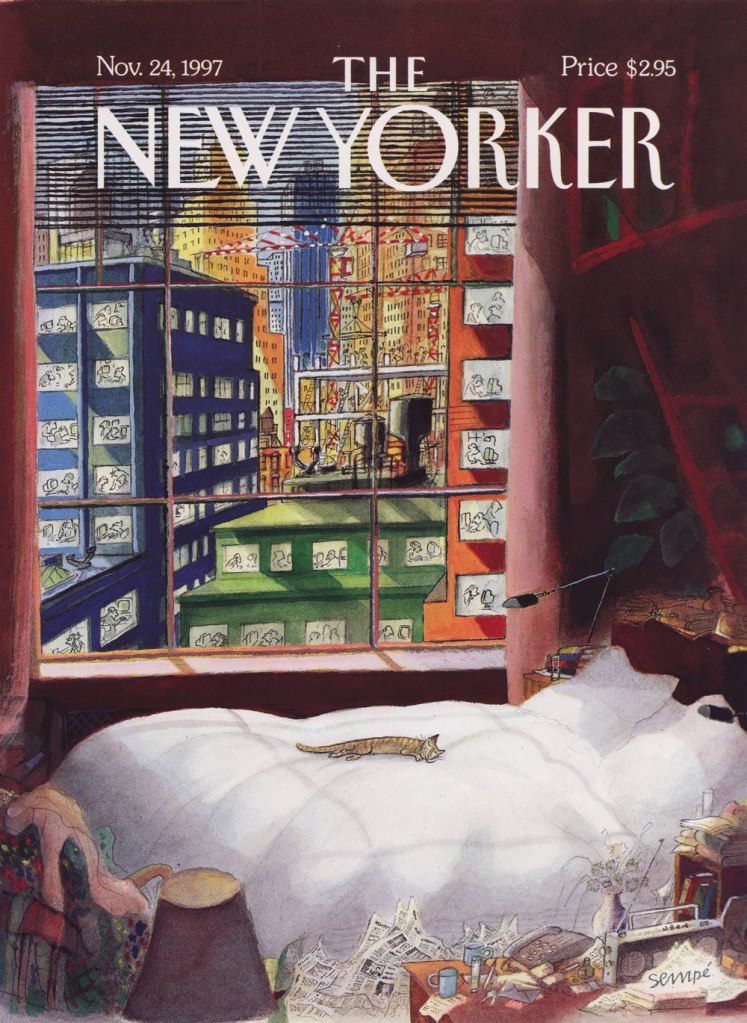

*see our posts on, alphabetically (or in any order you please!): Aldebert, Anton, Barbe, Bidstrup, Cabu, Desclozeaux, Effel, Folon, Fred, Gourmelin, Henri, Hoffnung, Lada, Pichard, Ramponi, Sempé, Topor, Wolinski… so far.