« My collection of criminal creeps will get a real charge of hokey hassle of heroes! » — The Collector

Just last week, I read the bittersweet news that after half a century or so*, the evergreen, once-ubiquitous Archie Comics Digests are kaput… which brings us, in the usual roundabout fashion, to today’s post.

Though it’s been nearly three years since our big move, I expect to carry on practicing box archeology for a good long while, if not indefinitely. A couple of months ago, I dug out an Archie Digest I had picked up at my local newsstand back in 1981… and quite possibly never read. Until this year.

I’ve mentioned before that comics distribution was extremely spotty in my neck of the woods, so I often found myself glaring and wincing at the racks in desperation and taking home some ungainly specimen*. This was such a case, obviously.

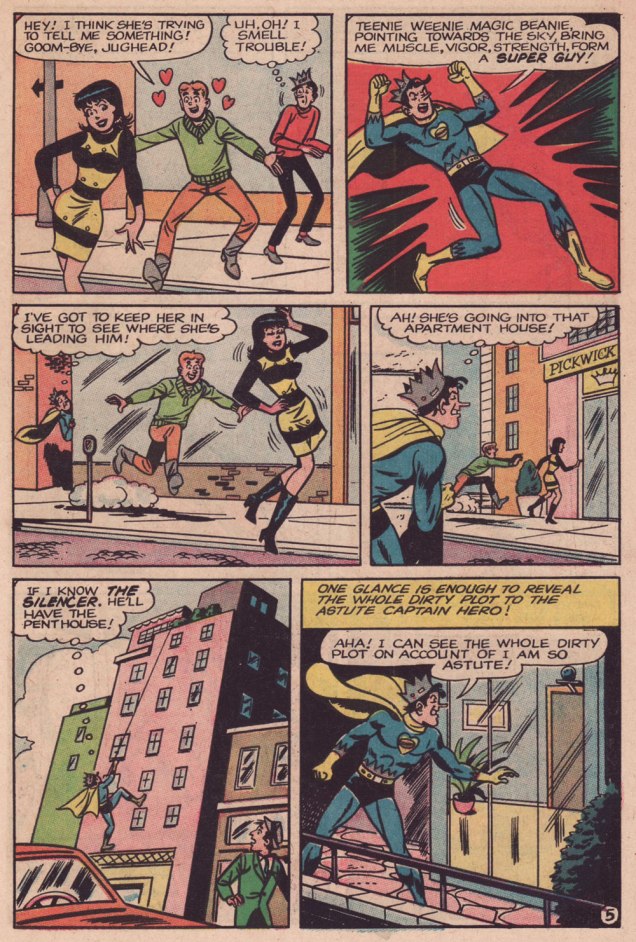

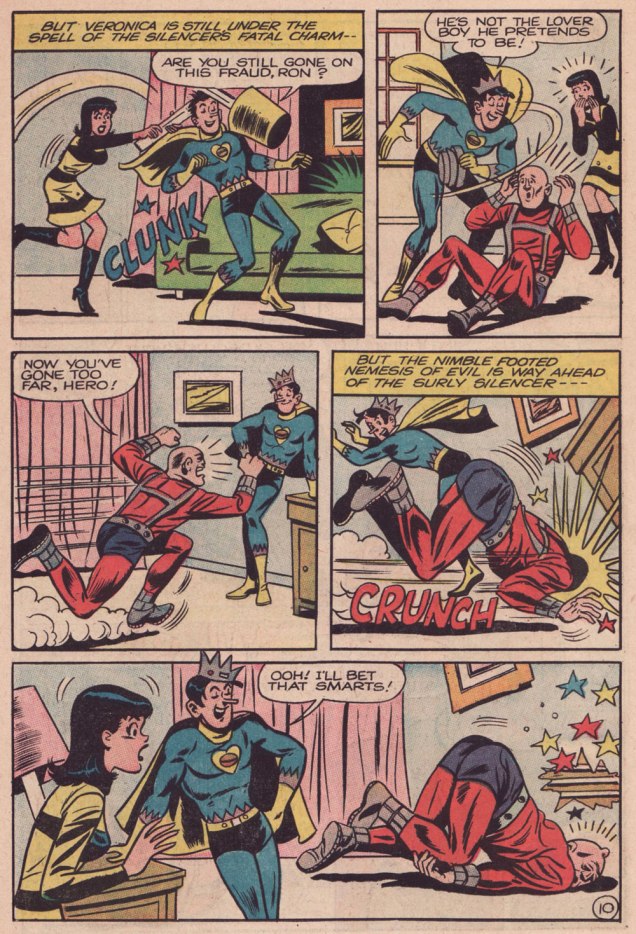

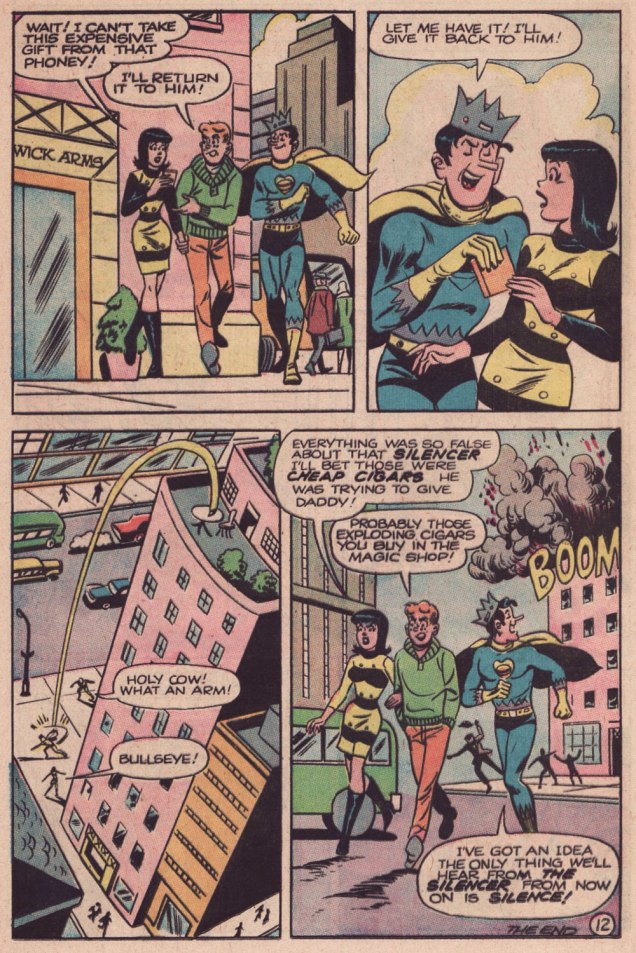

The Riverdale-Gang-as-Superheroes of the mid-1960s, just another bit of trend chasing** by the Archie brass, has never elicited much beyond a shrug from me. It certainly was intended as a cynical, junky cash grab by the higher-ups, but… sometimes it rose above the brief.

Bart Beaty wrote, in his 12 Cent Archie (2015, Rutgers University Press), that « On the whole, while the Pureheart material is remembered — and collected in contemporary trade editions — for its novelty within the Archie universe, it is clear that the innovation was not a particular success. The combination of Archie sensibilities and superheroes paid few dividends. »

Well, innovation wouldn’t quite be the term I’d opt for, but while the Pureheart stories are as underwhelming as surmised, but since Jughead, Reggie (as Evilheart) and Betty (as Superteen) are more interesting characters than plain ol’ Arch, it is fitting that their exploits are more compelling.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

While Bill Vigoda (1920-1973) is hardly anyone’s favourite Archie artist, he does a creditable job here; he’s having more fun with this material than he did on the regular Jughead title, where he had the unenviable task of replacing (ha!) Samm Schwartz.

-RG

*this also goes on in bars, I’m told.

**namely the rise of Marvel’s superheroes and the success of the campy Batman tv show, if you must know.

***Though they reaped the most bountiful rewards from the format, Archie were tardy — as usual — in adopting the digest: for instance, Gold Key had tried it out in 1968 with some Disney reprints, followed by collections of their mystery titles. DC had issued a one-shot Tarzan Digest in 1972. Marvel issued its own — slightly larger — digest in 1973, The Haunt of Horror, but it wasn’t comics, but a doomed attempt at reviving the moribund ‘Pulp’ format; finally, Archie entered the fray two months later, with Archie Comics Digest no. 1. Only Harvey lagged behind; unless I’m mistaken, it wasn’t until 1977 that some Richie Rich digests hit the glutted market.