« Better to have a lousy character than no character at all. » — Alain Delon (Nov. 8, 1935 – Aug. 18, 2024)

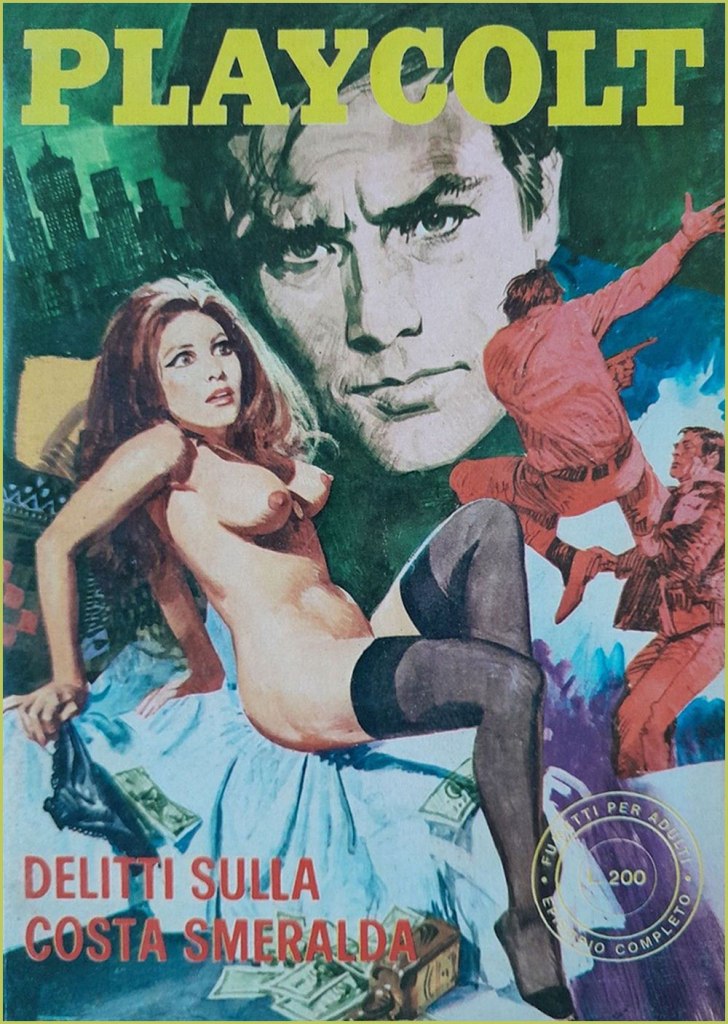

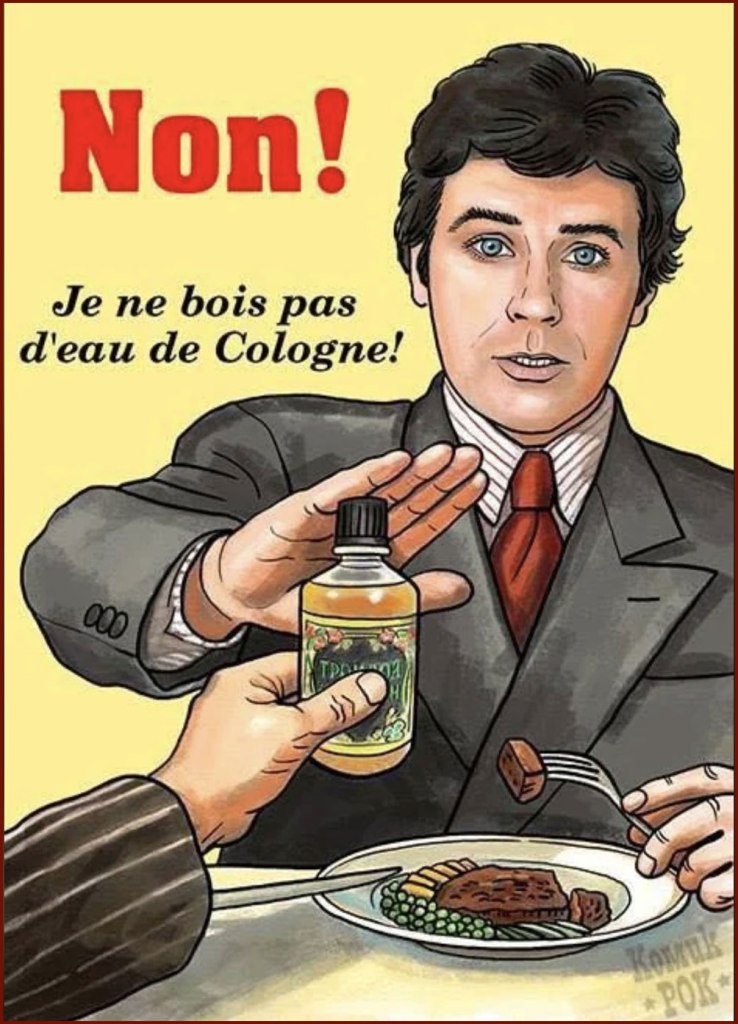

Quite recently, we lost monstre sacré Alain Delon. He was a complicated man, a bit of a prickly bastard, but he sure made a lot of great movies*. But comics, you ask? Well, I’m sure he never asked for it, but like many a celebrity (Jean-Paul Belmondo, Ornella Muti…) his famous countenance was appropriated by those incorrigible rascals at Edifumetto and Ediperiodici.

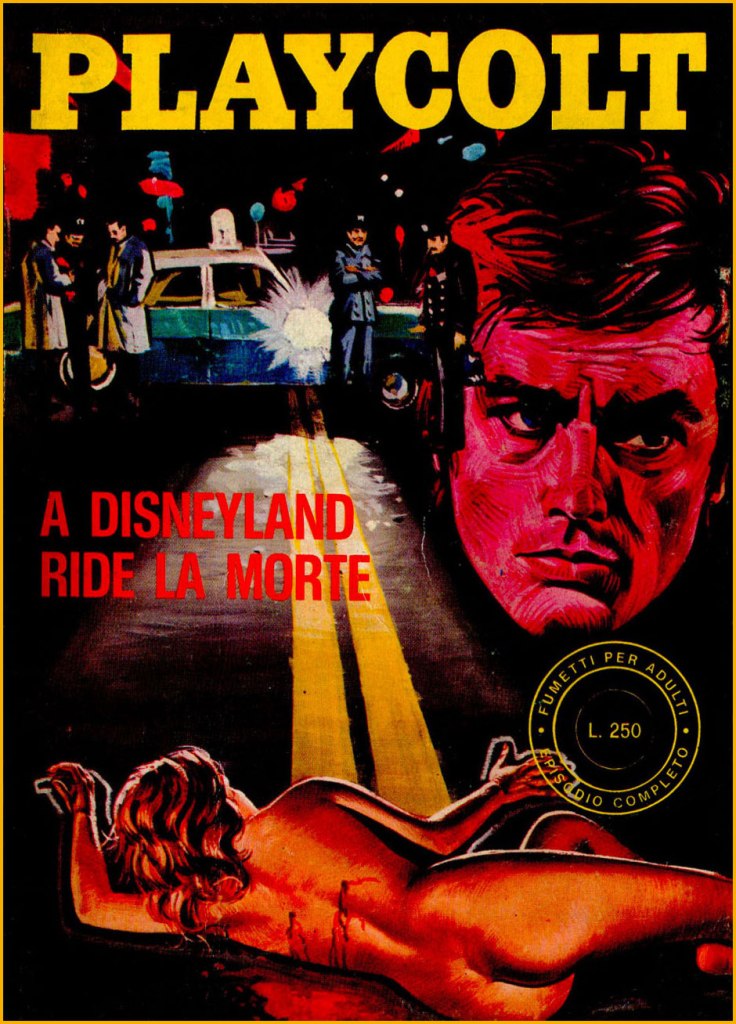

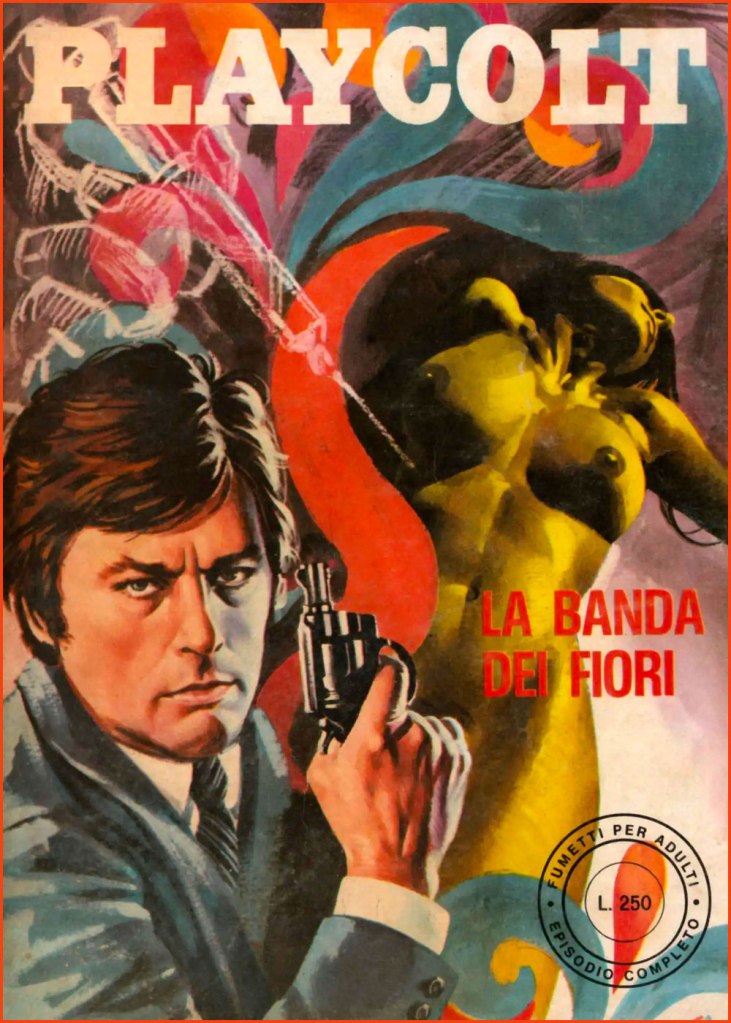

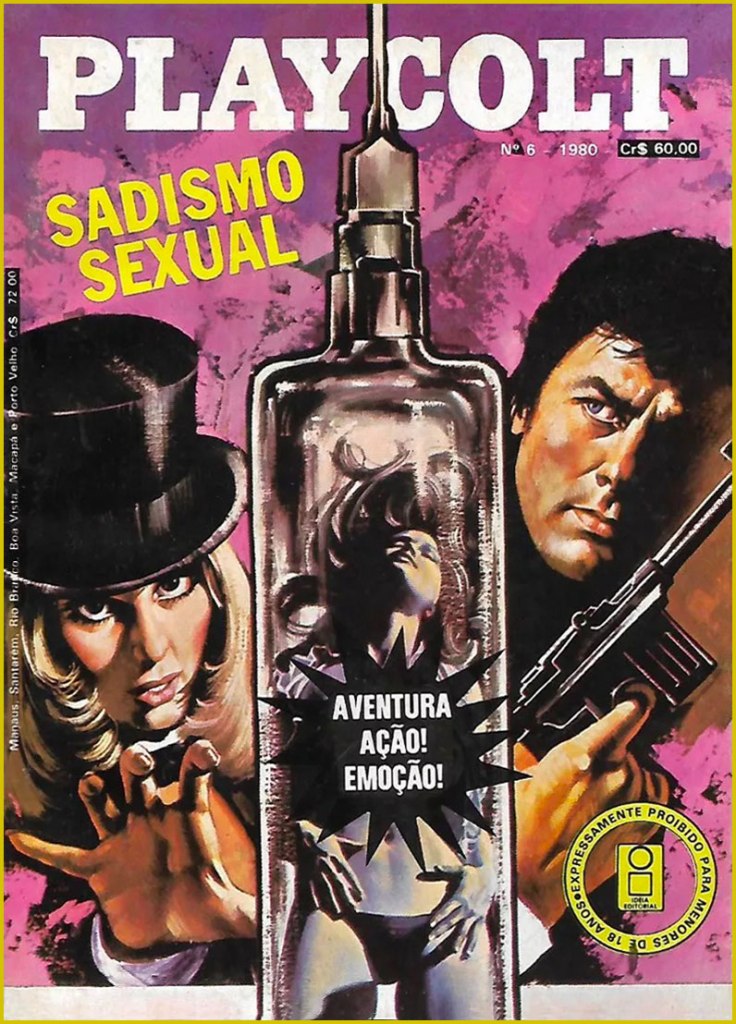

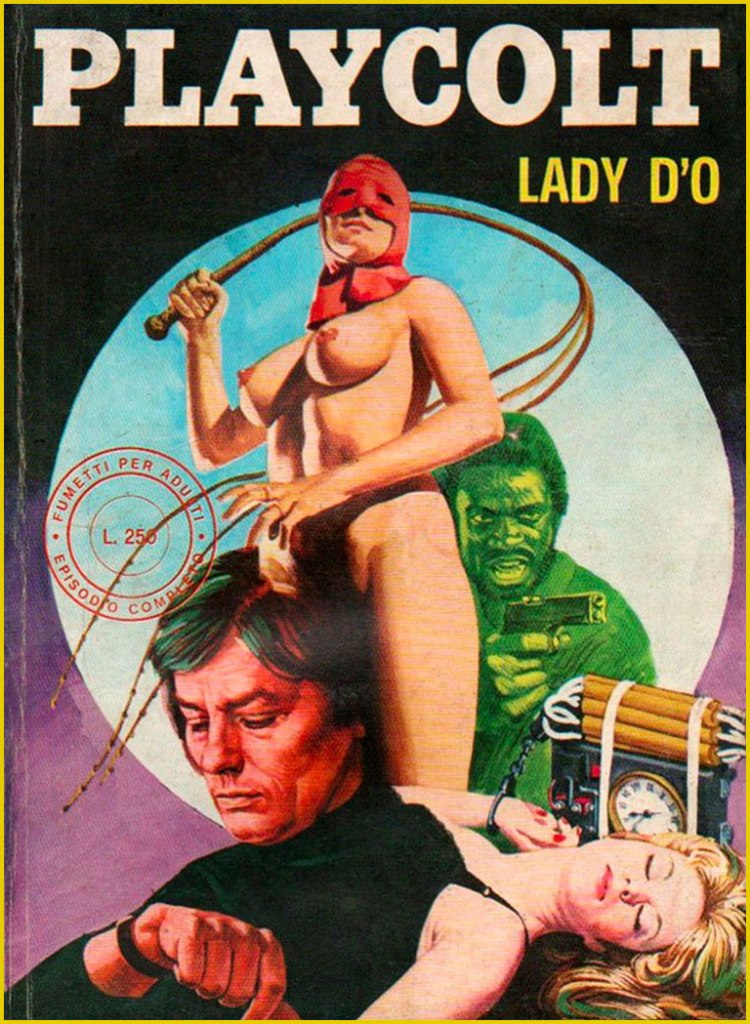

So Alain Delon became… « Alain Velon, a billionaire playboy who lives on an island “a 3-hour flight from New York“. He spends his private life conquering women in a continuous stream even if he is already engaged to the film actress Lizzy Scarlett, but “due to his innate sense of justice” he periodically transforms into Playcolt, a sort of superhero. His enemy is Linda Darnel, also a billionaire: sadistic and fetishist, she turns into the anti-heroine Za the Dead. Another historical rival is the always sadistic but lesbian Mandrakka. »

Now don’t get me wrong: these are virtually unreadable, poorly drawn, sadistic, illogical, reactionary misogynistic claptrap. But the covers are fascinating in their gonzo way, randomly cobbling together purloined bits from famous likenesses to established logos. You’d think this brazen wave of wholesale filching would have led to swift and decisive legal action from several stars’ solicitors, not to mention Hugh Hefner’s… but it seems not. This was, after all, the Italy that gave us Silvio Berlusconi.

There was, concurrently, another Delon homage in Jean Ollivier and Raffaele Carlo Marcello‘s successful Docteur Justice, a humane but hard-hitting series about a physician and expert judoka who roams the globe’s trouble spots for the World Health Organization. There was even a film adaptation in 1975, with John Phillip Law essaying the title role… and co-starring Delon’s ex — and only — wife, Nathalie. Among Pif Gadget’s adventure series, it was only bested in popularity by the prehistoric blond heartthrob Rahan. I’ll tell you more about it one of these days.

-RG

*So claims the Russian pop song entitled Взгляд с экрана, and who are we to doubt it?

**I recommend Adieu, l’ami, Red Sun — both co-starring Charles Bronson — La mort d’un pourri, Jean-Pierre Melville‘s Le Samouraï and Le cercle rouge, Plein soleil… as cinema’s first Tom Ripley.