« A reader has the right to ask for all the facts; he has no right to ask that a journalist or historian agree with him. » — Herbert Matthews

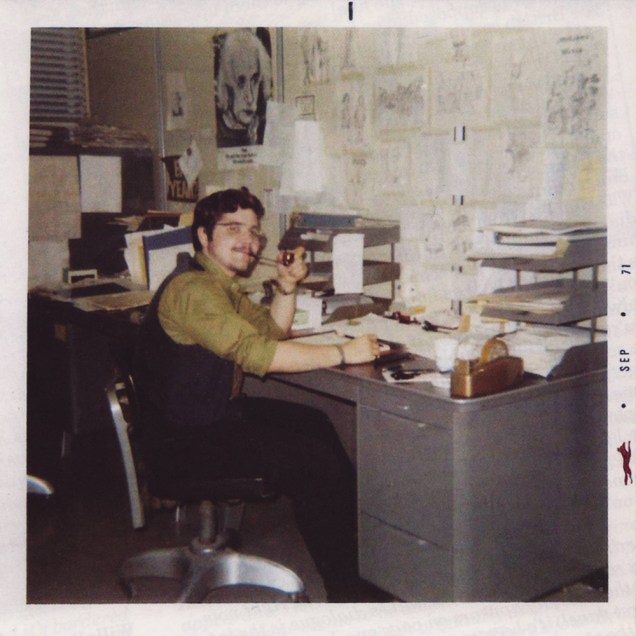

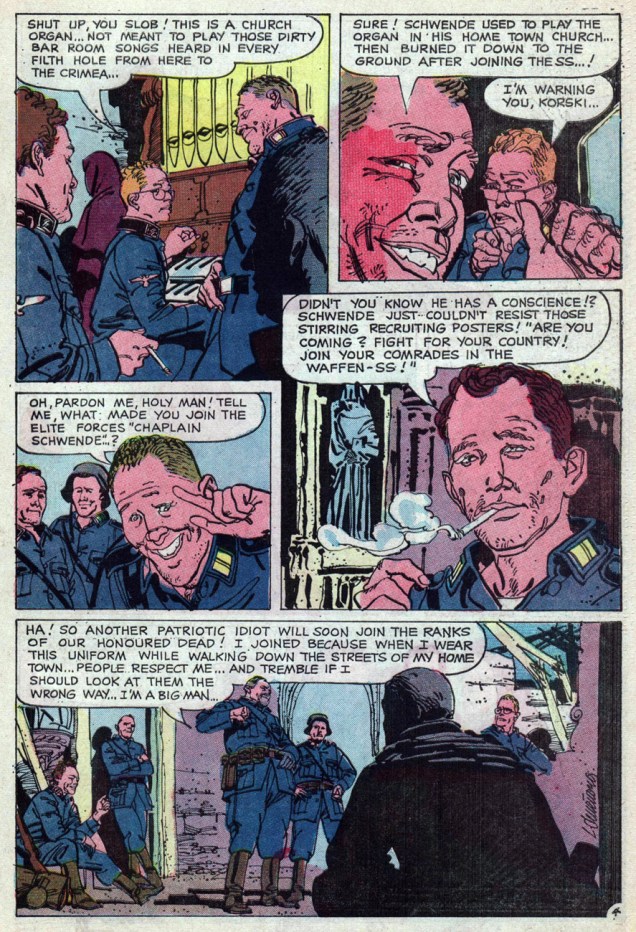

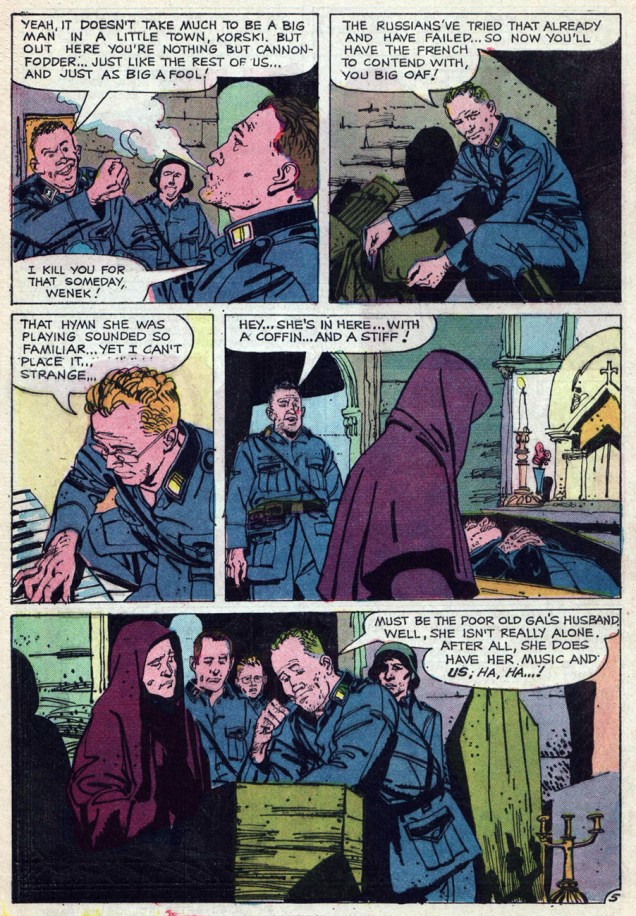

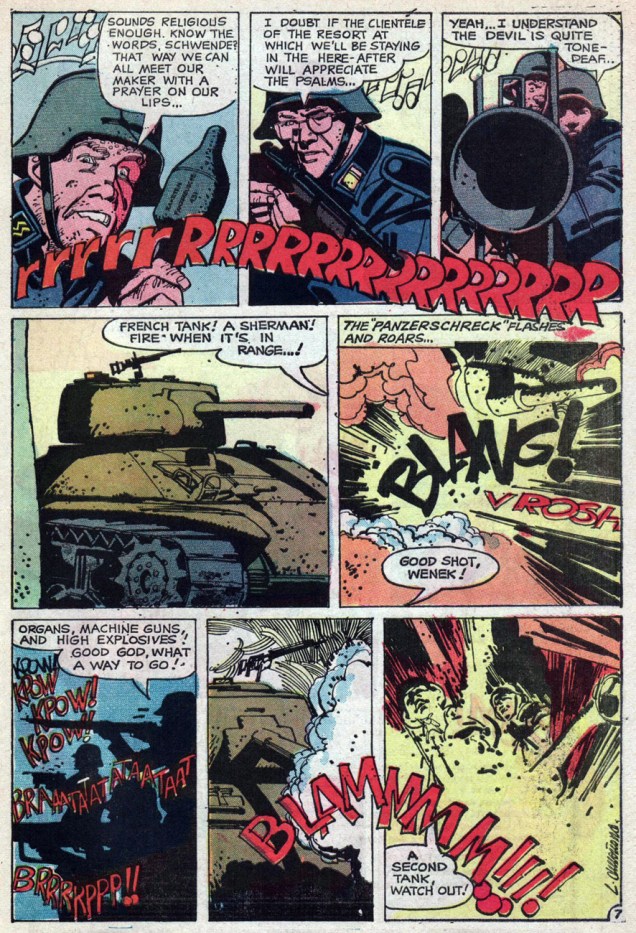

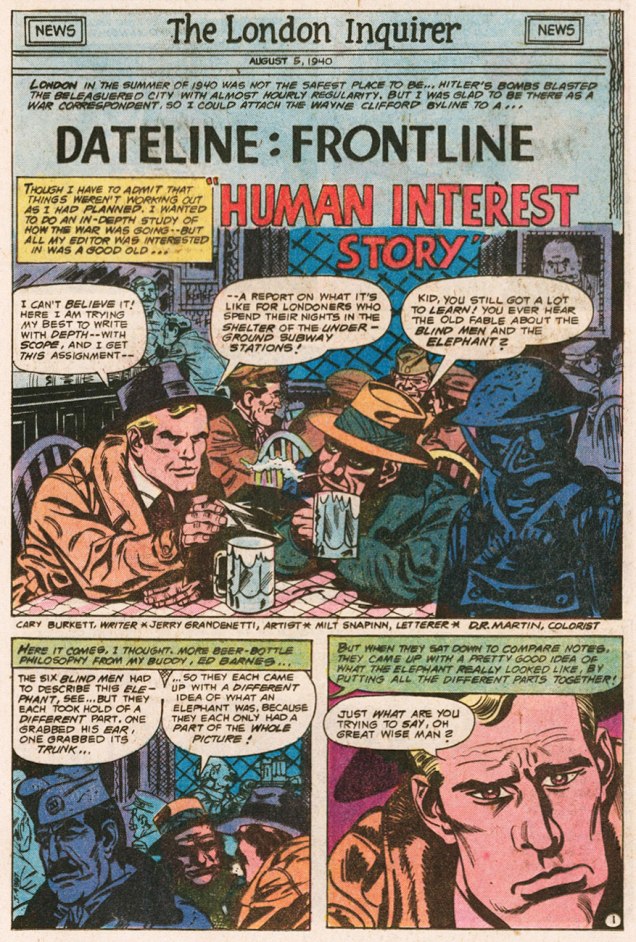

And we’re back with part two of our examination of Cary Burkett and Jerry Grandenetti‘s Dateline: Frontline (we’re not forgetting the famously-ambidextrous Ric Estrada, who took over illustrative duties in the second half of the series). In part one, Mr. Burkett graciously opened for us a window on the series’ genesis. In light of these privileged behind-the-scenes gleanings, as well as a reading of the series’ springboard text, Phillip Knightley’s The First Casualty, I formulated a series of follow-up questions, of which we present the first half, along, of course, with Mr. Burkett’s insightful and modest responses, followed by chapter 2 of the first D:F trilogy.

Who’s Out There: Was there much deliberation on your part regarding the specific setting of the series?

Cary Burkett: I vaguely recall that in an early meeting with Paul Levitz we mentioned the possibility of setting the series during the Vietnam war. Or rather, I think he may have mentioned it. But I never had any interest in that from the beginning. That war was too close at the time, and I didn’t think I could do it. Research was a lot harder to do in those days, and I was too green as a writer to want to tackle that controversy.

If my memory is right, I think he left it up to me, and I very quickly settled on the World War II setting. There were a lot of reasons in my mind for that, including the wealth of research material available.

But the biggest thing was the fact that the U.S. started out as “neutral” in that war. I felt a story arc right away of a young reporter who began as a “neutral” observer, wanting to be an objective journalist, but over a series of events finding himself unable to keep from being drawn in and taking sides, despite his proclaimed neutrality.

At the time I didn’t know how long the series might last, but it was my intention to gradually move Wayne Clifford from a naïve journalist with laudable ideals into a conflicted character grappling with the very gray areas of war reporting and the messy questions of patriotism and propaganda.

WOT: In writing the series, did you ever find yourself at odds with the, er, ‘official record‘ of history?

CB: I wouldn’t say that exactly. The truth is, I had only a sketchy knowledge of World War II history, and little idea of what the “official record” said. So I set about to educate myself.

One really good current documentary at the time was The World at War narrated by Laurence Olivier. I watched a number of episodes of that. What I realized from watching it was how much the history I had heard and read was centered on how the U.S. and England had won the war. This documentary was one of the first western pieces which really pointed out the importance of the Russian contribution.

That led me to other research and made me want to do a series of stories set in Russia. Of course, the insane difficulties of trying to report the truth during a war in the middle of Russia appealed vastly to me and provided a lot of opportunities for conflict on a lot of levels. I felt I barely scratched the surface in those Russia stories.

One thing about doing research; you start to get interested in all the little details. You want to include much more than you really can. You have to be careful to let the story reveal the details when it is important to the story, but not to let the research itself become the story.

I struggled with that in writing those Russia stories, because much of what I was finding out was really eye-opening to me. What I knew about the war in Russia I had learned mainly from watching Hogan’s Heroes. In that TV comedy, the Nazis all feared being sent to the Russian front, so you knew it was cold and terrible. But that’s about all I knew.

When I began to read about the scope of the tragedy and brutality of the war in Russia, I wanted to bring the reality of it into my stories. I wanted to shove it all in somehow. But my stories were a mere 6 pages long in each issue, so I had to just try to give little glimpses that implied a lot more.

Stephen King’s advice to writers is to “kill your darlings”, that is, to get rid of your pet favorite bits so they don’t bog down the story. Those Russia stories were ones where I felt I had to keep killing those “darlings” over and over.

WOT: Was there any friction with DC’s brass, or was the series too far under the radar for them to notice? If so, did that allow you more leeway?

CB: We were definitely way under the radar, but I don’t think that the stories would have caused any stir even if they had been noticed. I don’t think there was anything subversive or strongly controversial about them. They were different from the usual comic book war stories, but not in a way that would cause any issues.

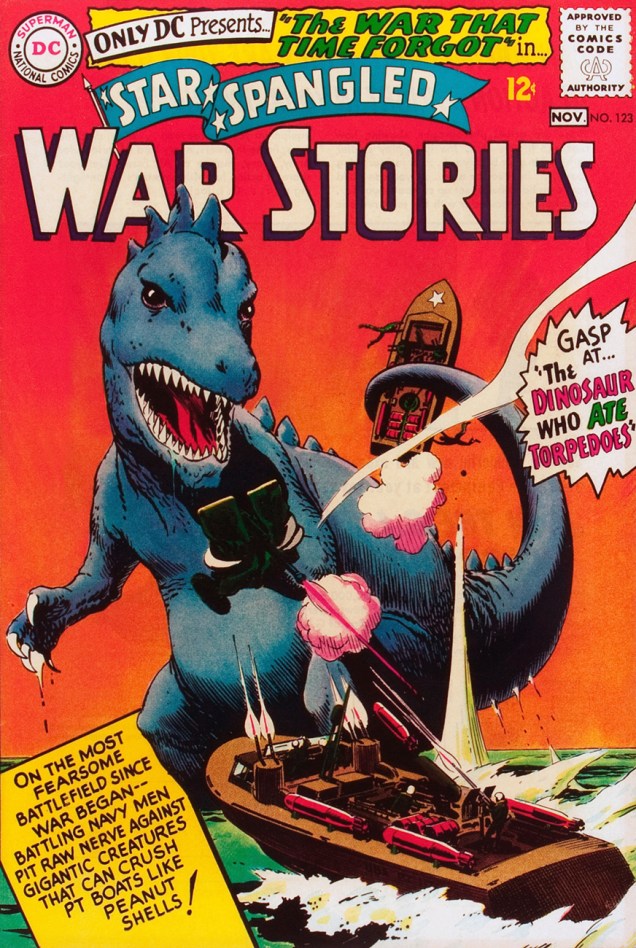

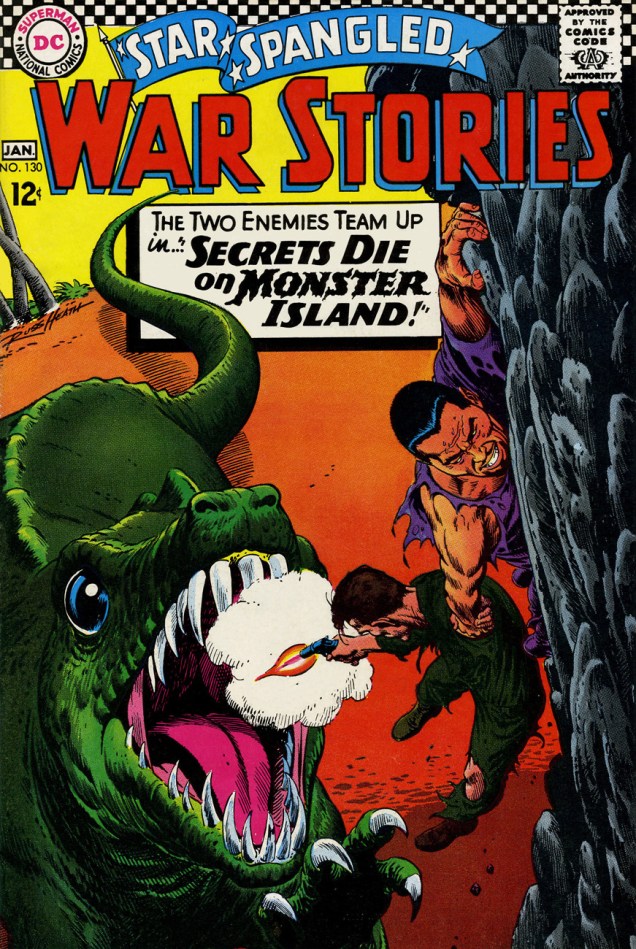

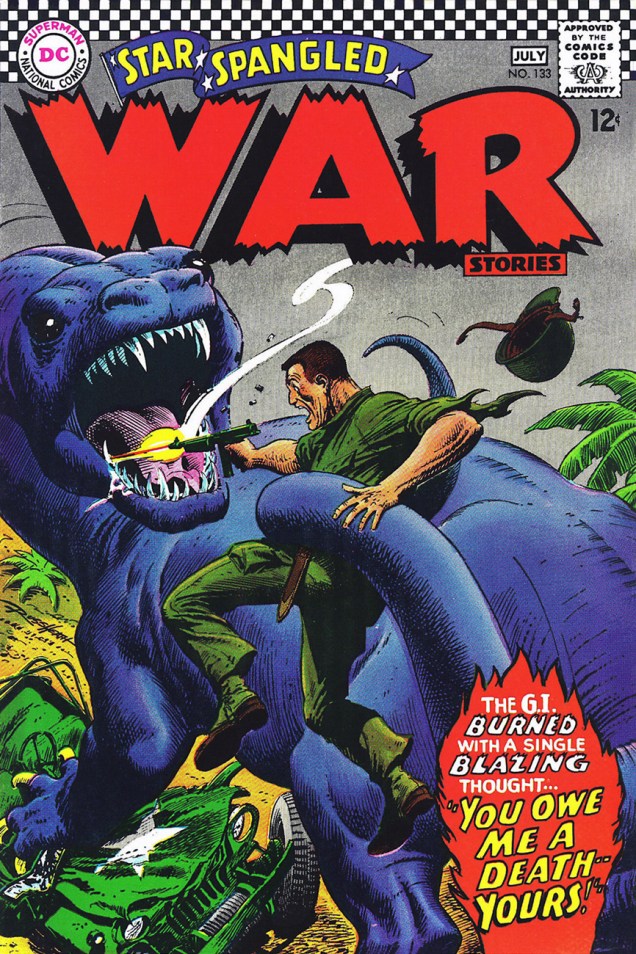

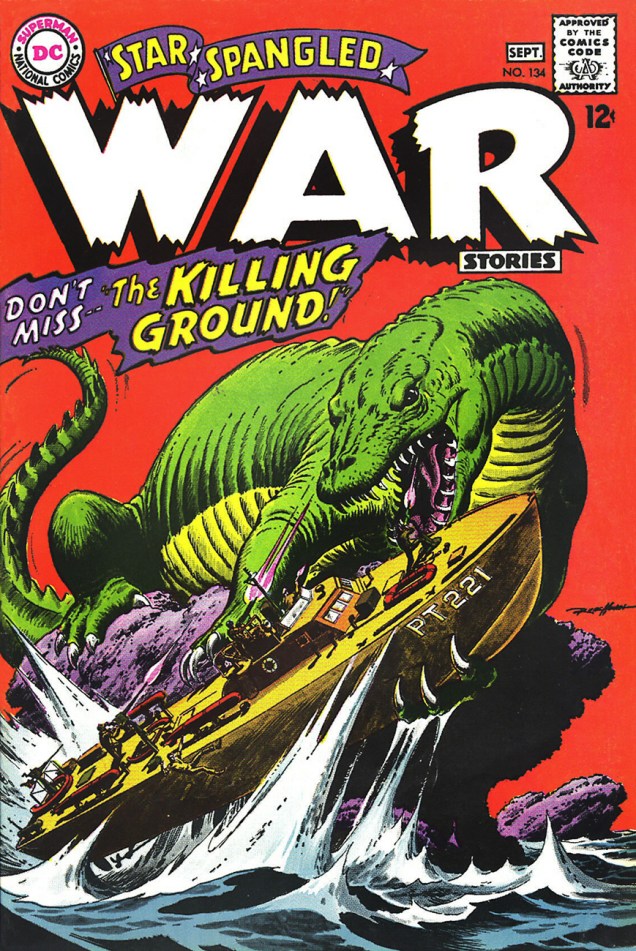

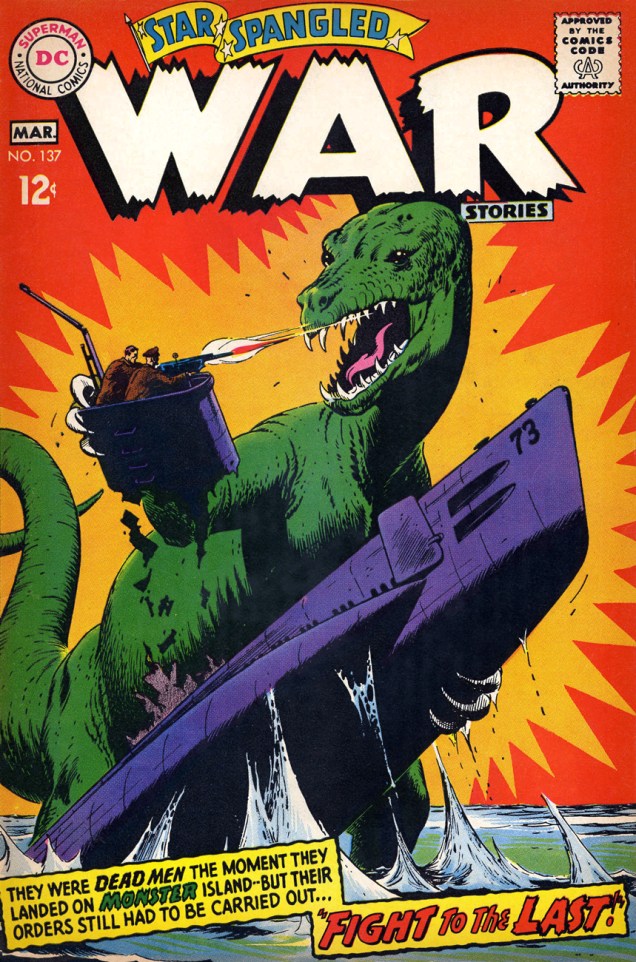

The lead stories of the books featured Gravedigger, or later, The Unknown Soldier. These were the stories that were there to sell the book, and these would have gotten more scrutiny. They were the typical action-oriented comic book war stories, sometimes just a step away from fantasy. Sometimes not even a step.

With a long-running lead character in a war series, you have to be a bit looser with timelines in the war. I suppose it’s a convention of the genre that the character might pop up in Okinawa in one story, then many issues later have a story related to D-Day, even though D-Day would have happened well before Okinawa.

Maybe it’s because the main character was a journalist who was dedicated to getting the facts right, but I decided that my timeline was going to be accurate. The series would start with the U.S. as a neutral country, and we would later see the USA join the war, and all of the historical events would follow in the order they occurred.

WOT: Was the rotation of backup features decided from the start? Was it some sort of commercial compromise?

CB: I don’t really know. I think the idea was mainly to have variety in the backups. It was a common template for older DC titles like Action Comics or Adventure Comics in the ‘60’s. One issue would have a Green Arrow backup, the next maybe Aquaman.

My own speculation is that as an editor, Paul was drawn to that kind of setup, and felt it gave the reader a little something extra. That’s just my own thought, he never told me that. But I know he was a comics fan, and I think he was glad to have a place where Enemy Ace could still fly through the pages of a DC Comic.

WOT: Given the wealth of material you dug up in the course of your research, it must have required considerable effort of concision to craft such spare chapters. Did you go through a lot of drafts?

I did struggle to find ways to get my stories into the six-page frame and did quite a few re-writes, trying to balance the pace so the story didn’t seem rushed but also had enough meat.

There were compromises, for sure. In what I considered to be one of the key stories, Clifford, still a neutral reporter, takes a rifle and kills an Axis soldier attempting to kill his English friend. I had been leading up to this decision since the beginning of the series. Here he is forced to admit that he is neither neutral nor objective as he thinks of himself. I would have loved to have had a bit more room to let that sequence play out with more significance.

No doubt, I could have done a better job even in the space I had. In the end, I felt that it came out a bit weak and contrived.

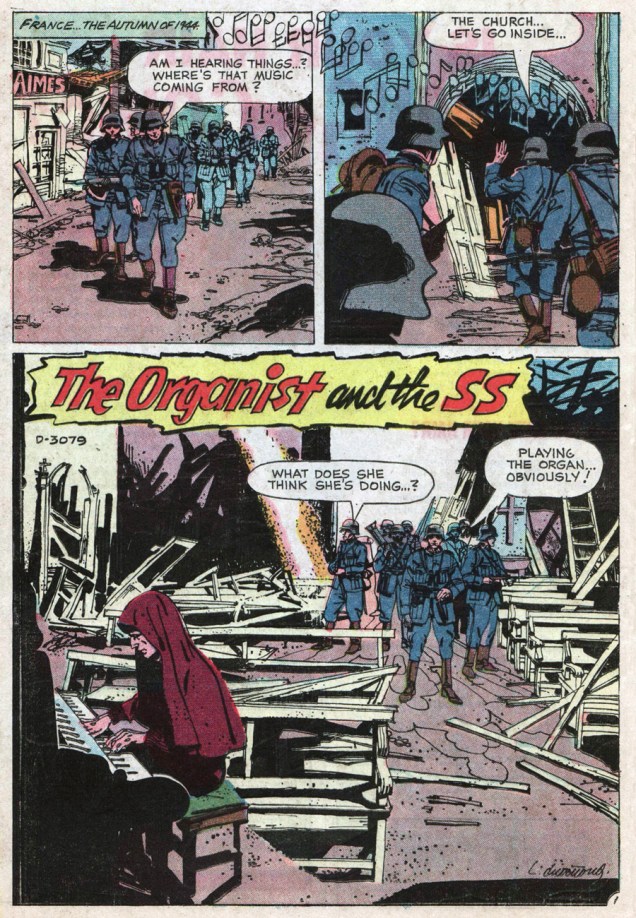

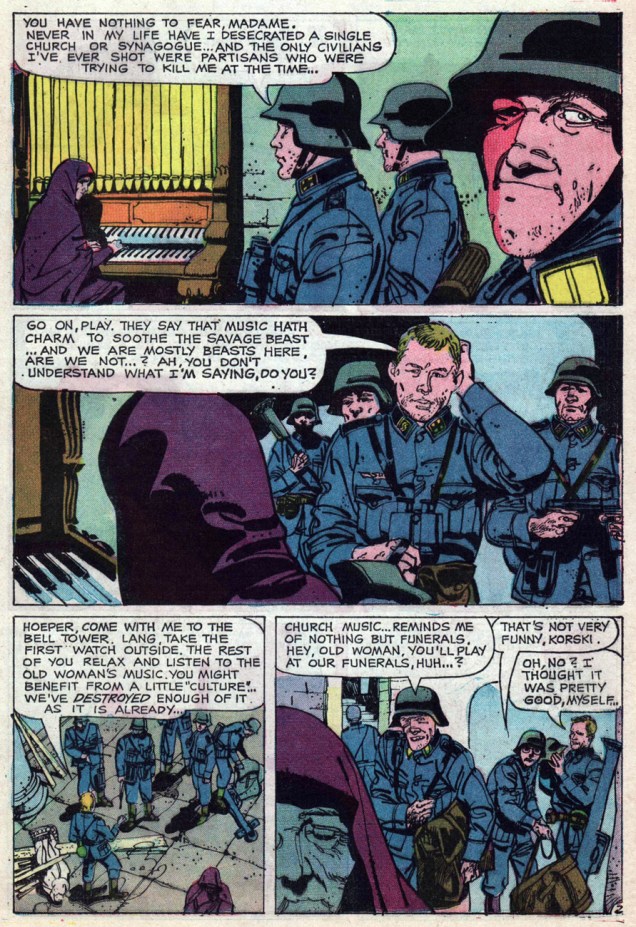

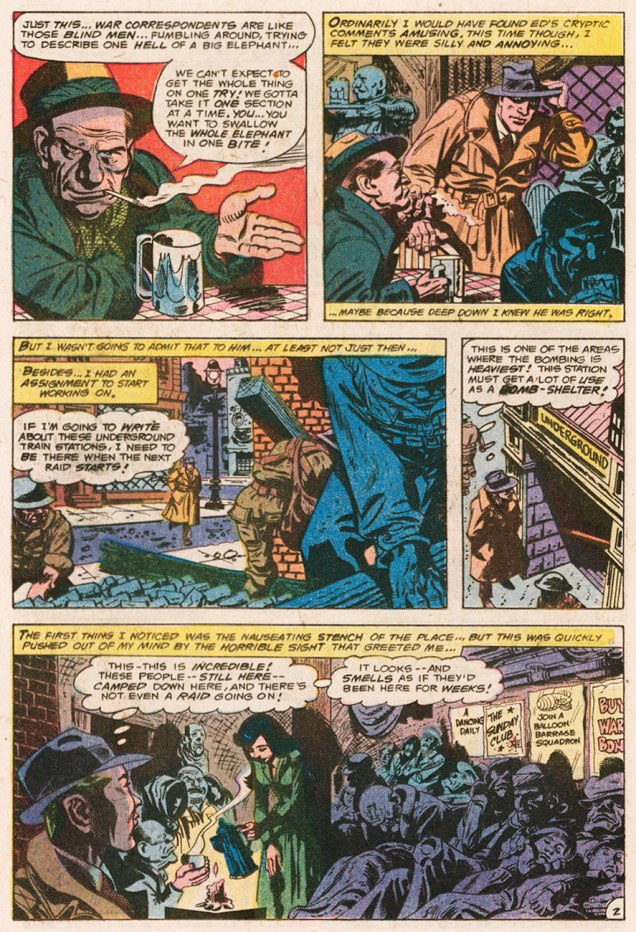

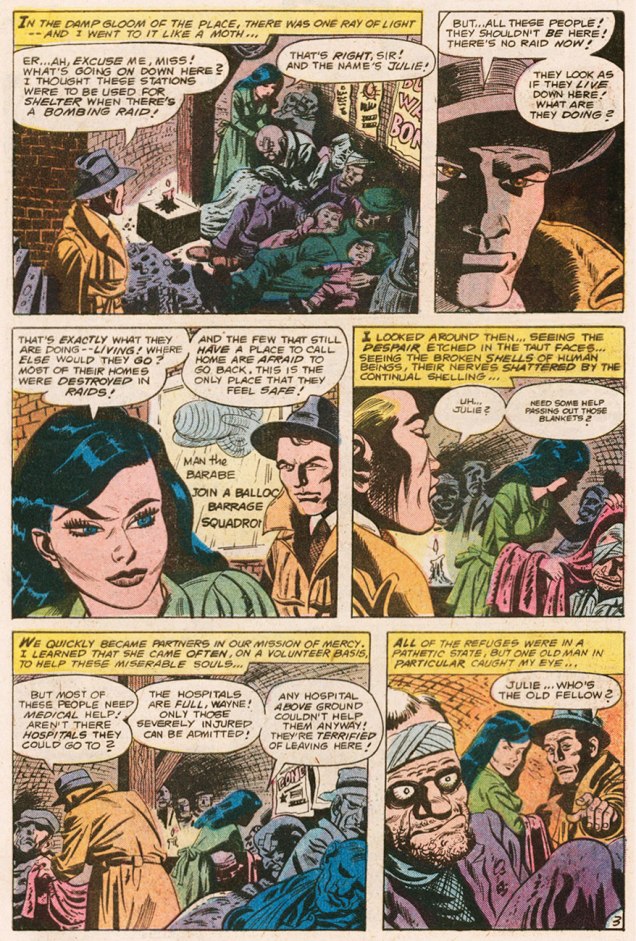

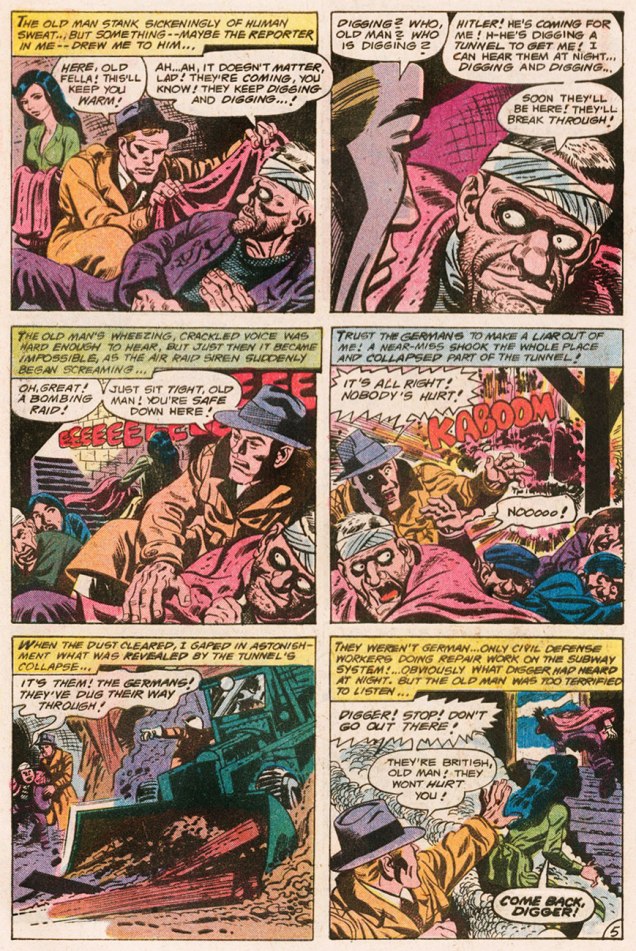

Now, let’s rejoin Wayne Clifford and his buddy Ed Barnes, who were, when we saw them last, off to the pub…

That’s it for now! Stay tuned for the conclusion of our talk with Cary Burkett, along with part three of Dateline:Frontline’s London trilogy.

-RG