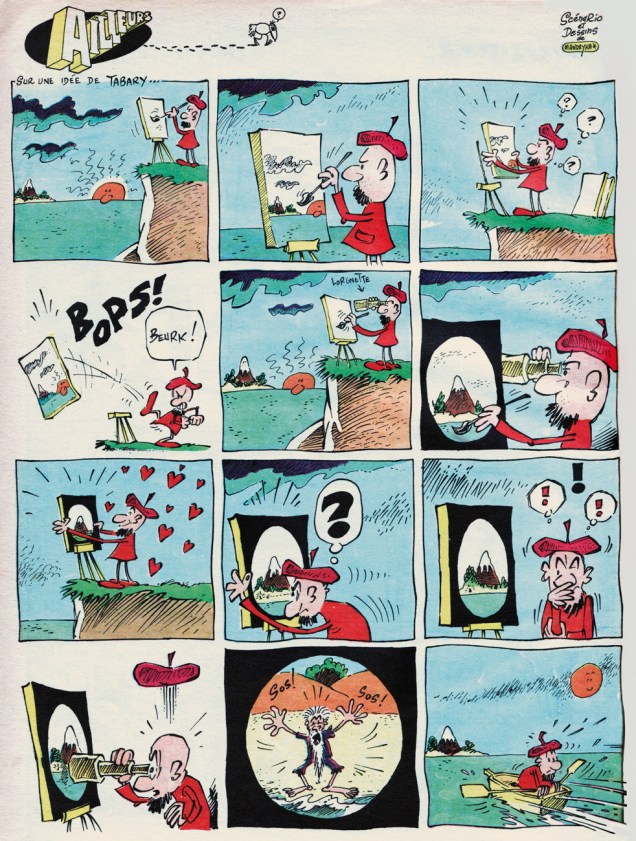

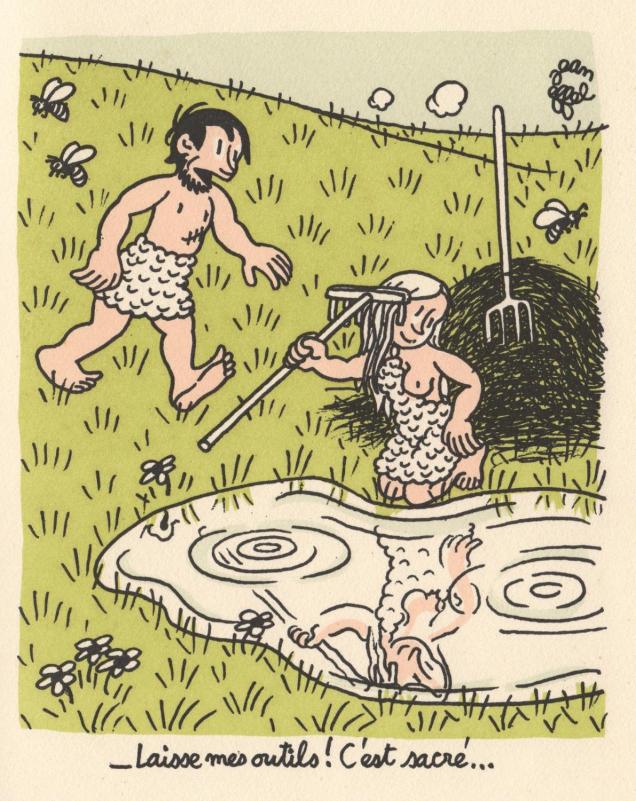

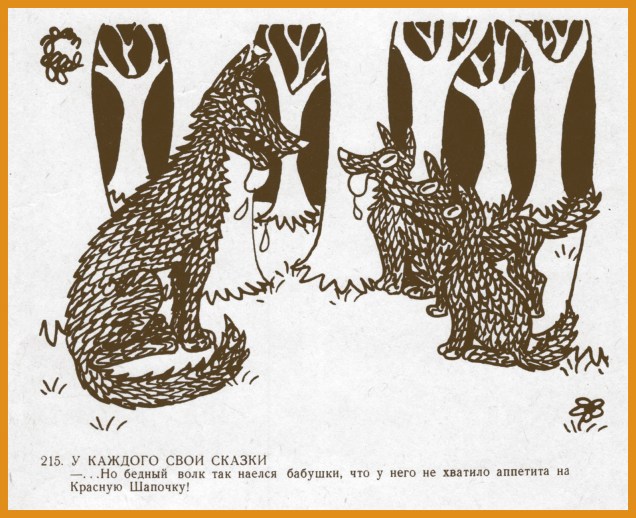

« The man who cannot visualize a horse galloping on a tomato is an idiot. » ―

What is one to do, in a mere blog post, with a polymorphous artist such as Maurice Henry (1907-1984)?

Here’s a handy bit of compressed biography, from his Lambiek page:

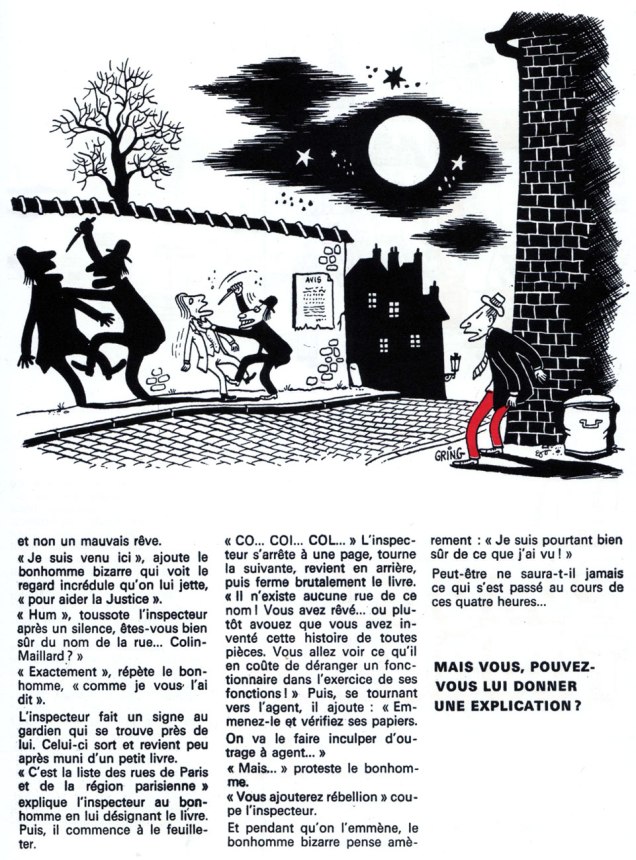

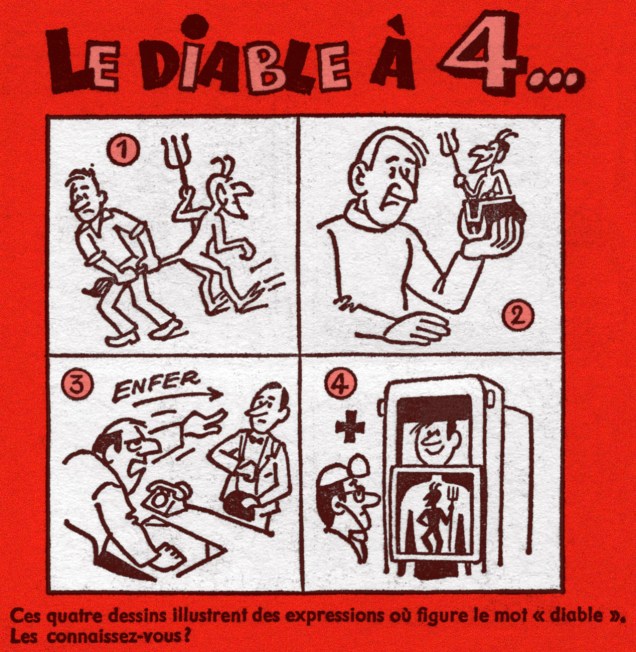

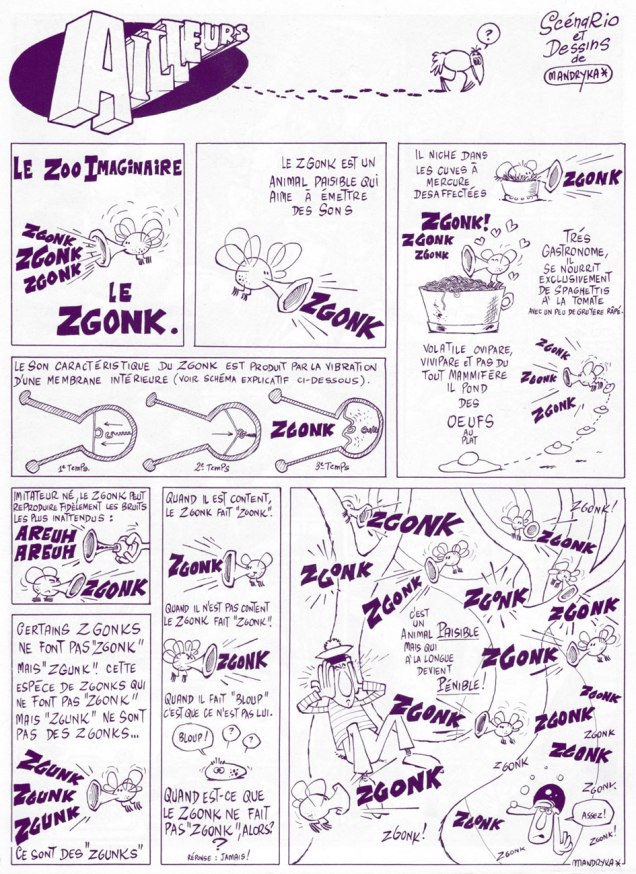

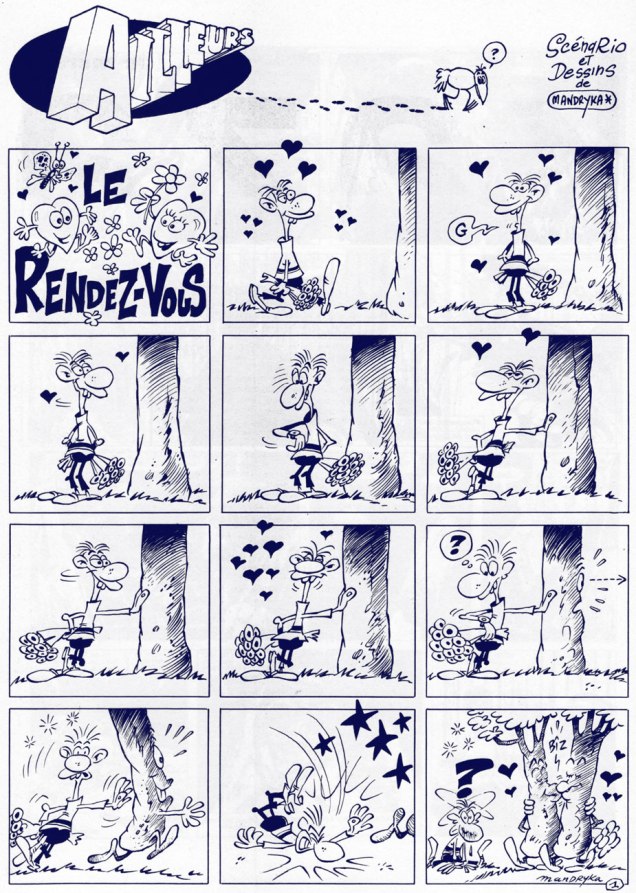

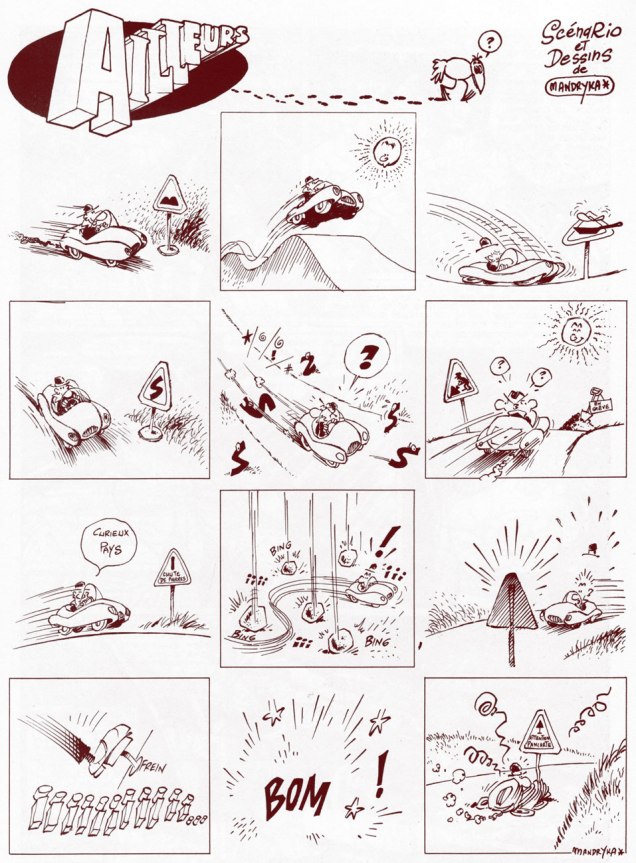

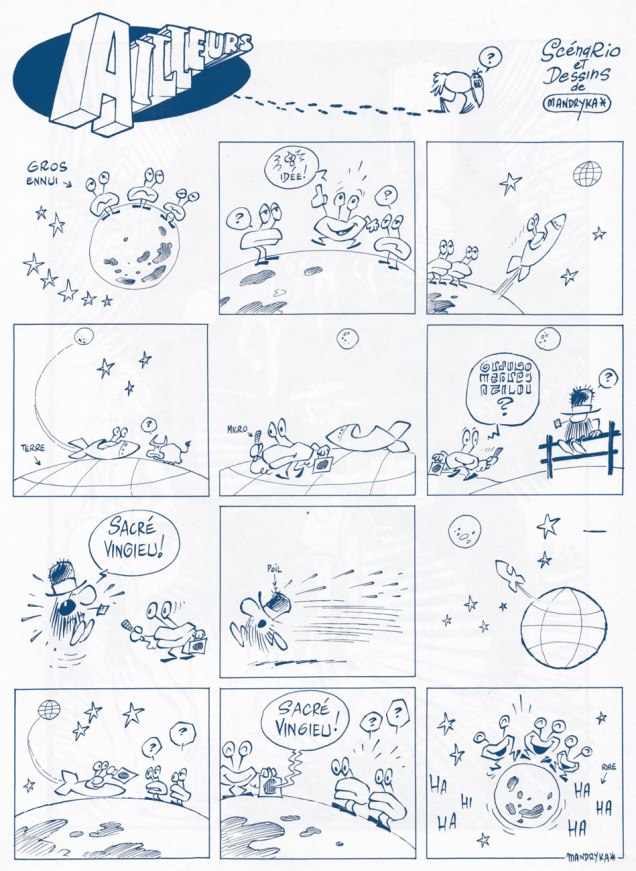

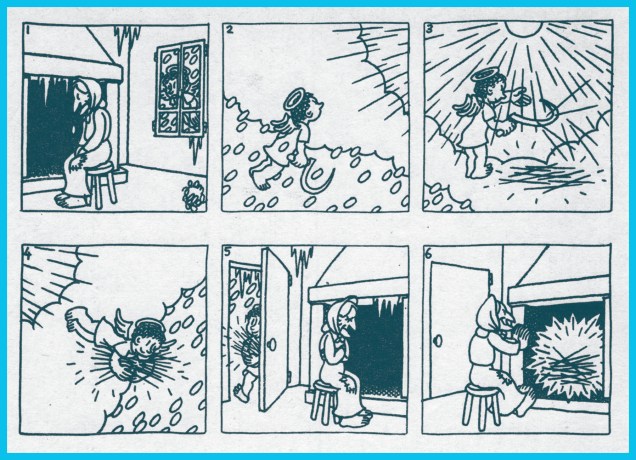

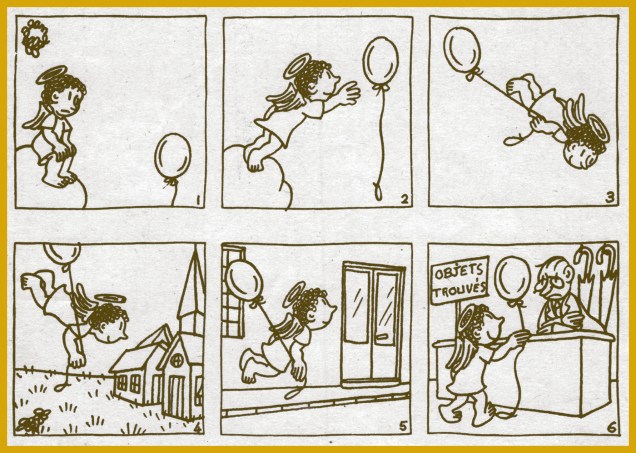

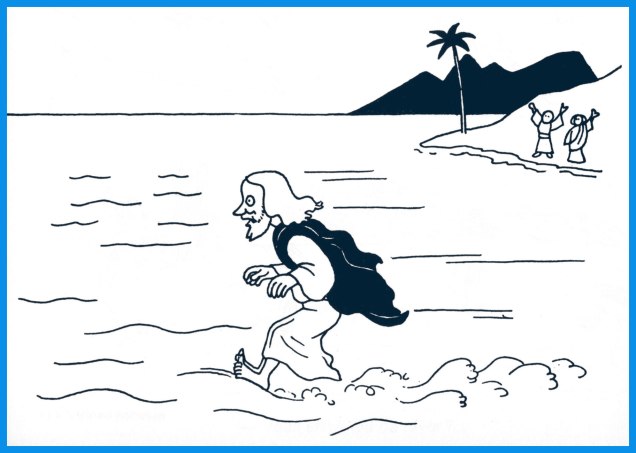

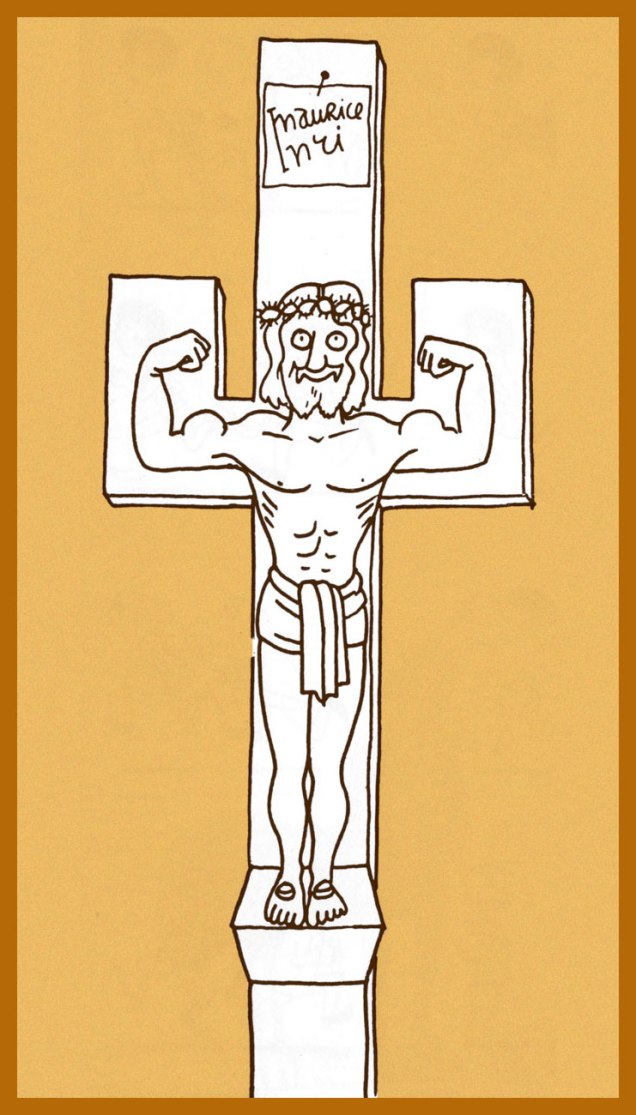

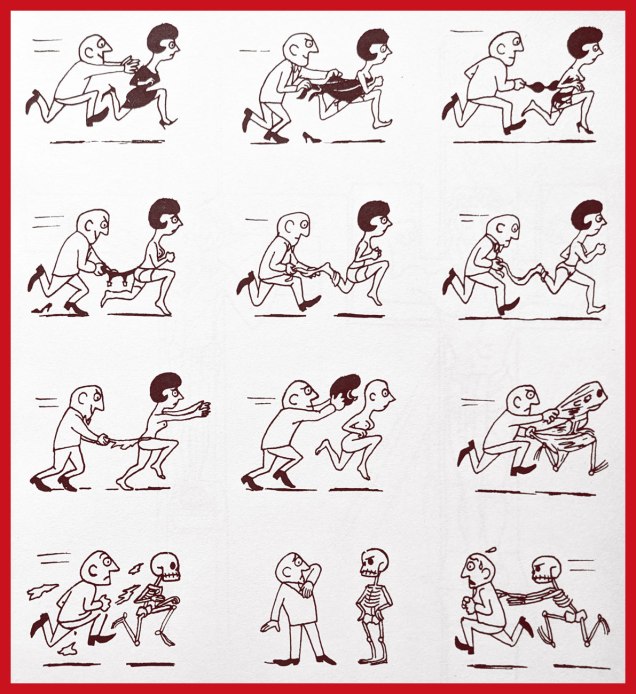

Henry was a French painter, poet, filmmaker, as well as a cartoonist. Between 1930 until his death, he published over 25,000 cartoons in 150 newspapers and a dozen books. His cartoons were generally surrealistic and satirical.

In 1926, he co-founded the magazine Le Grand Jeu with René Daumal, Roger Gilbert-Lecomte and Roger Vaillard, with whom he formed the “Phrères simplistes” collective. Henry provided poems, texts and drawings, while also making his debut as a journalist in Le Petit Journal.

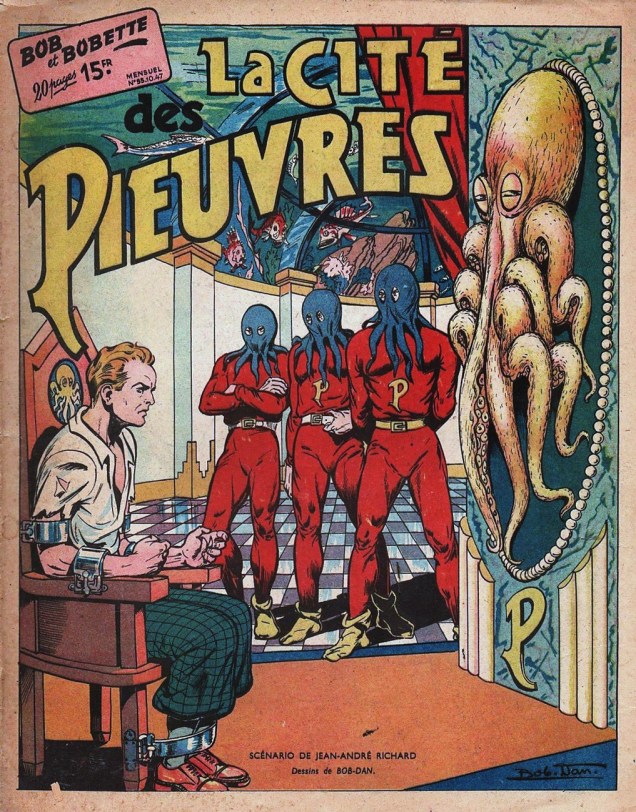

He left Le Grand Jeu in 1933 to join André Breton’s group of Surrealists and their magazine Surréalisme au service de la Révolution. He also worked with the artist and photographer Artür Harfaux on the screenplay of twenty films, including ones starring the comic characters ‘Les Pieds Nickelés’ and ‘Bibi Fricotin’. Maurice Henry spent the final years of his life making paintings, sculptures and collages. He passed away in Milan, Lombardy, in 1984.

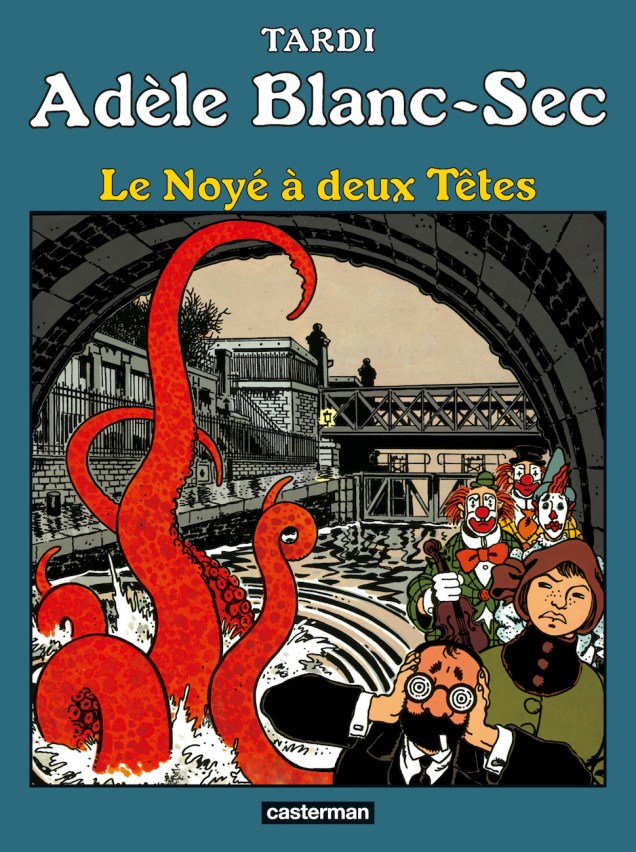

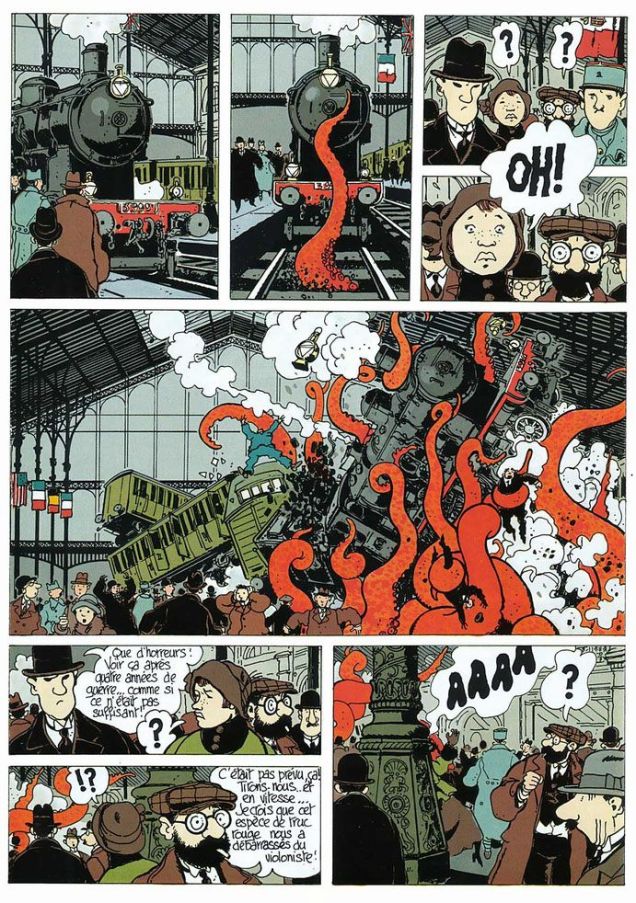

The answer? My default solution, which is to focus on some small parcel of the much greater whole. A number of Henry’s works bear revisiting (for instance, Les métamorphoses du vide [1955], a truly groundbreaking picture book about the world of dreams; À bout portant [1958], a collection of literary portraits; or Les 32 positions de l’androgyne [1961, also issued in the US in 1963], a chapbook of… gender recombinations) and deserve a turn in the spotlight.

To quote co-anthologists Jacques Sternberg and/or Michael Caen in their indispensable Les chefs-d’oeuvre du dessin d’humour (1968, Éditions Planète, Louis Pauwels, director):

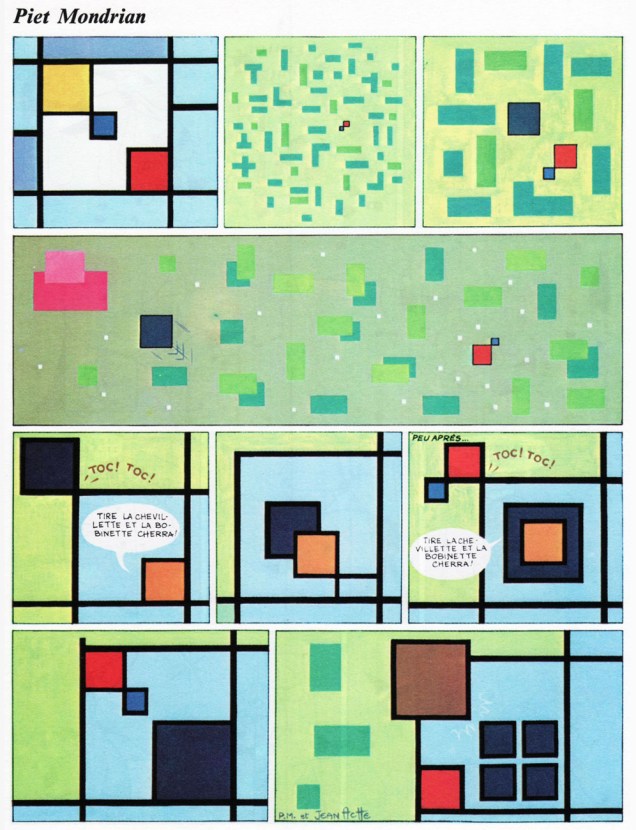

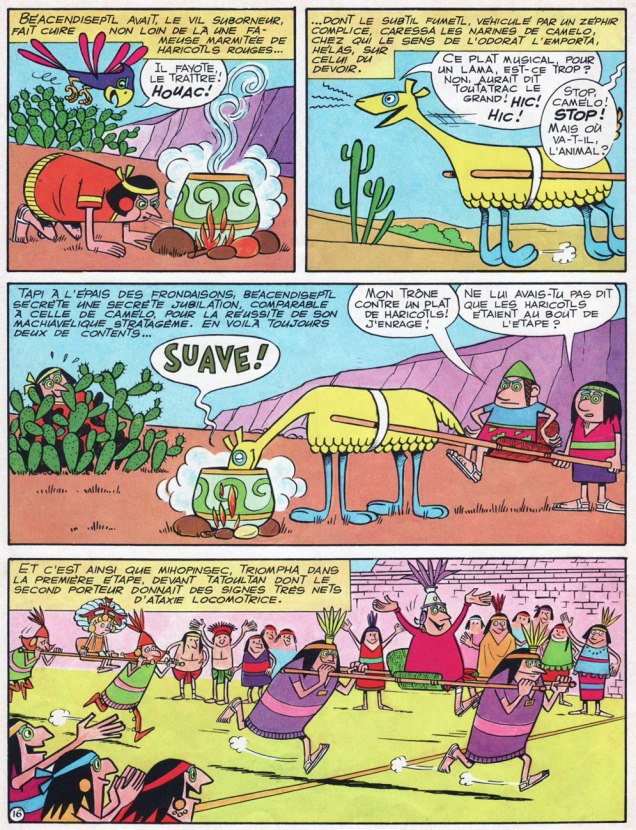

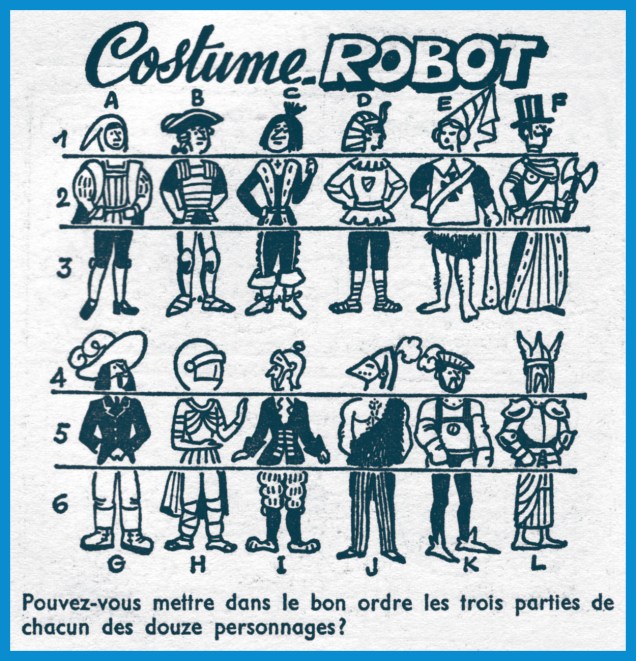

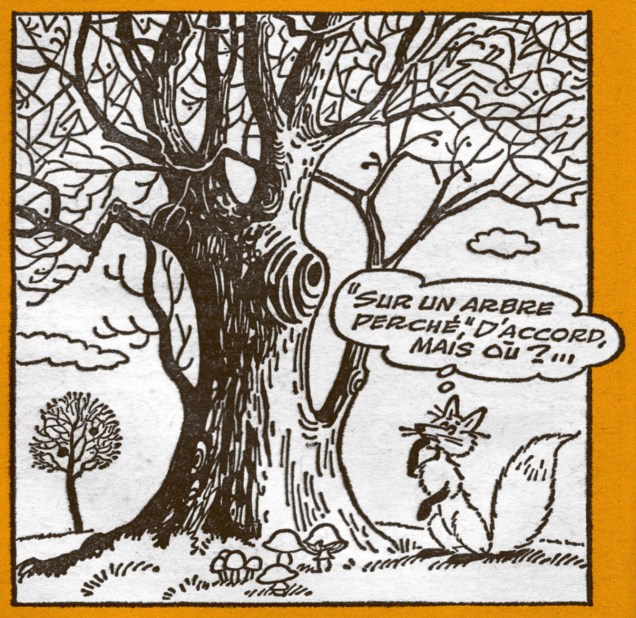

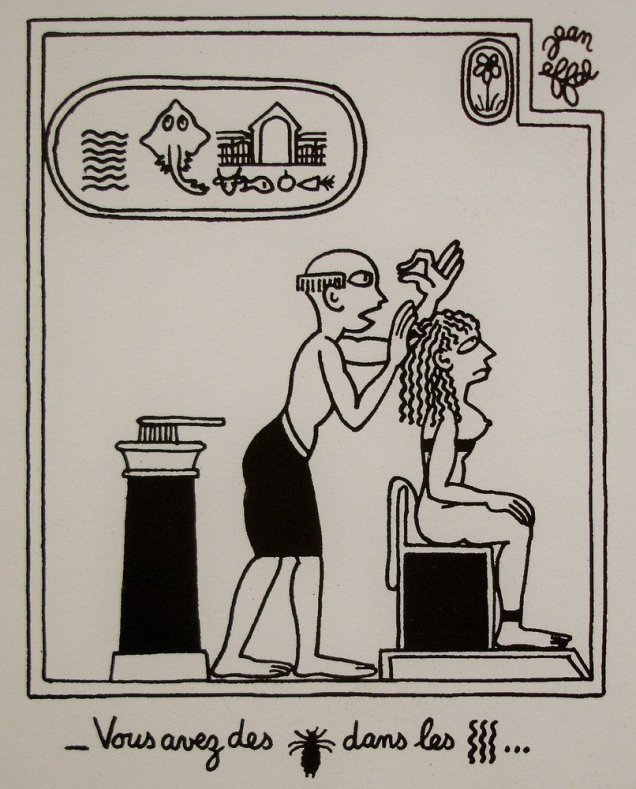

Surrealism — he was part of the group before 1930 — left its mark on him and it’s because he was already well-cultured as he launched his career that he was among the first, in the desert that was the publishing world of the 1930s, to attempt unusual drawings calling upon often startling ingredients, such as poetry, black humour, the fantastic and the absurd. He caused no less of a surprise by doing away with captions, at a time when bawdy jabbering was the fashion all over. In short, Maurice Henry was indisputably a pioneer of that grey and stinging brand of humour that would explode like an H-bomb some fifteen years later.

-RG