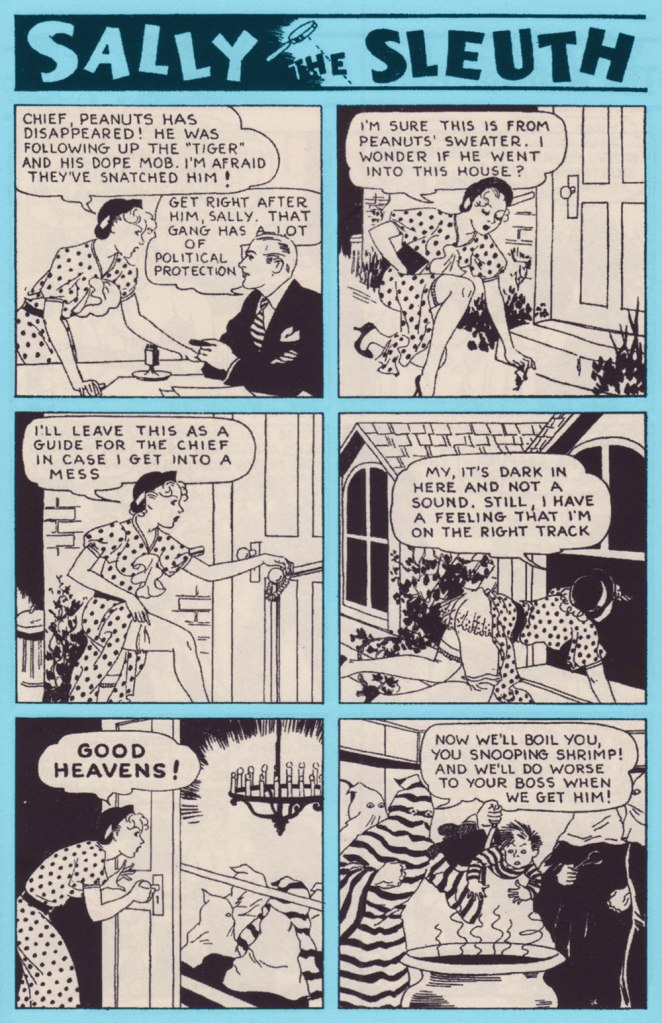

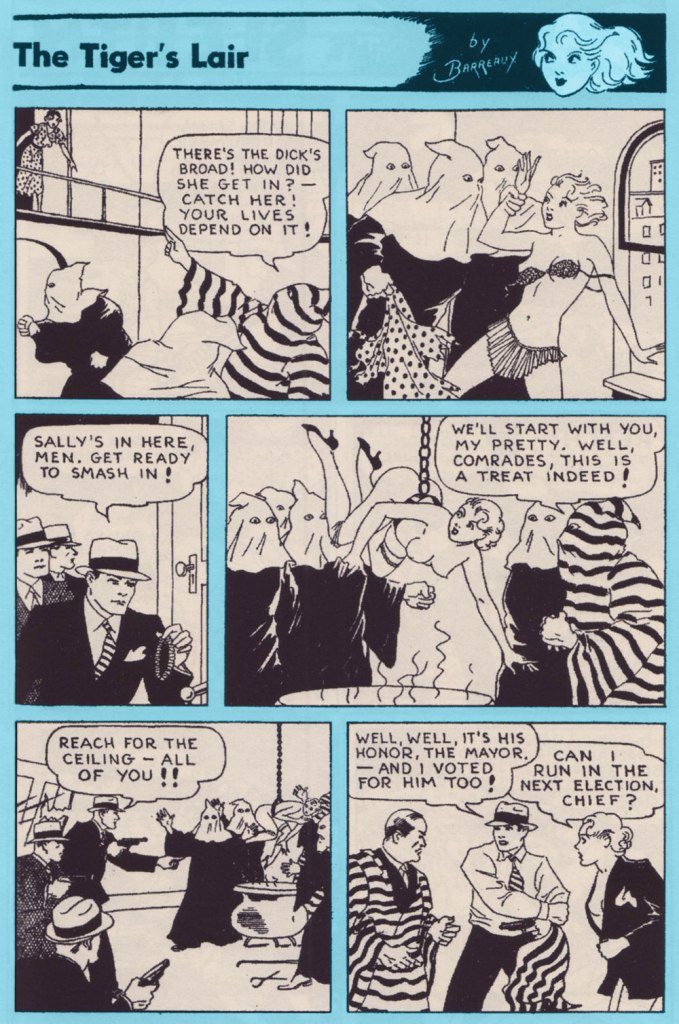

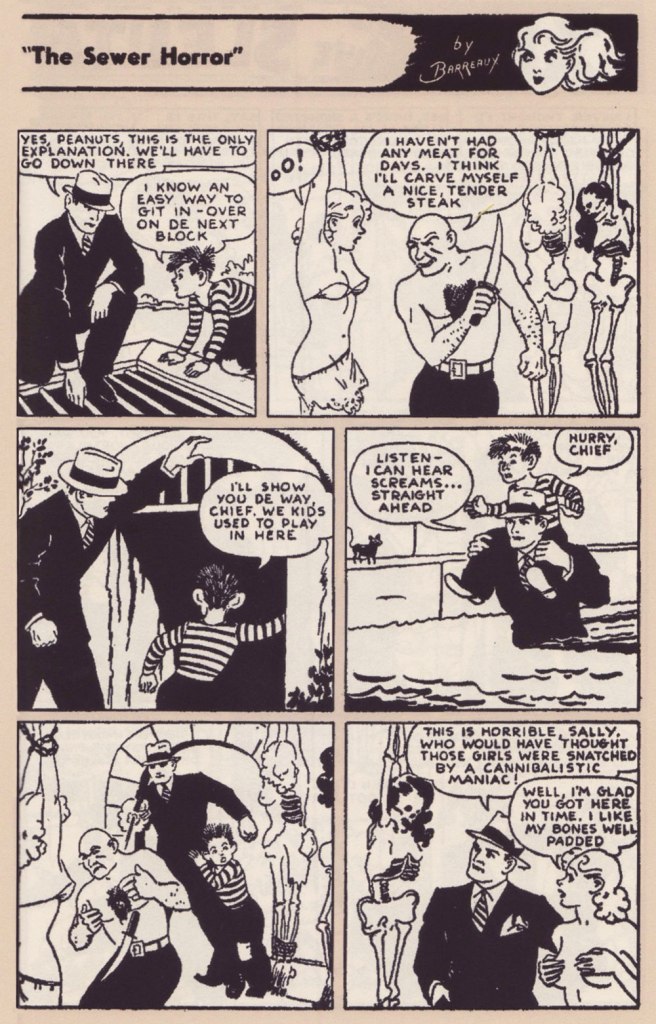

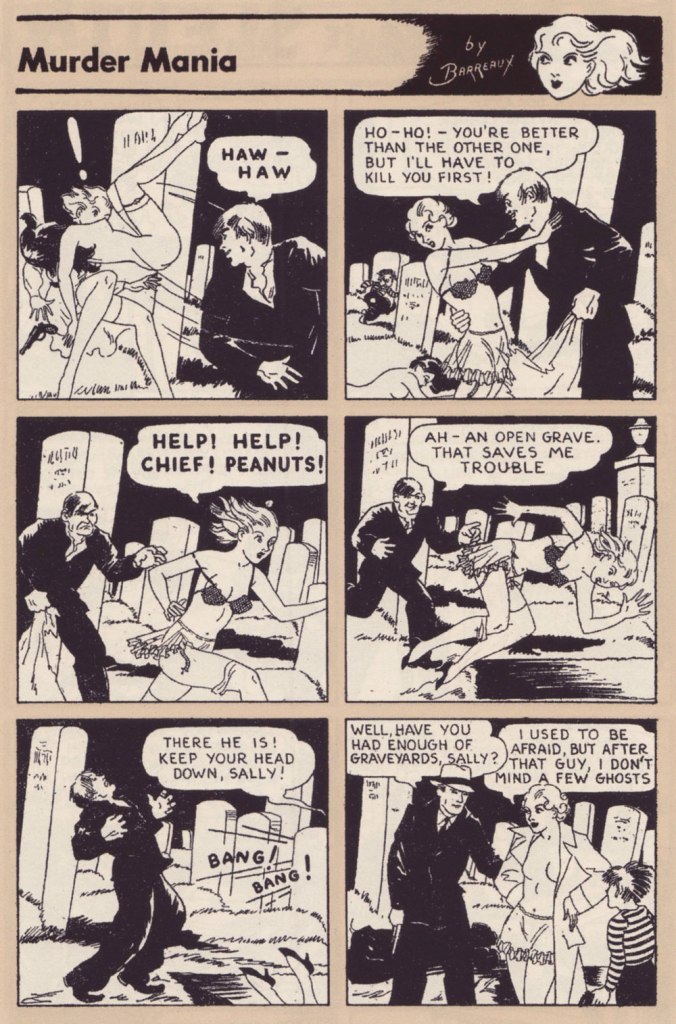

She’s audacious, savvy, and she’s always cheerful. Here she is, the infamous Sally the Sleuth by Adolphe Barreaux*. First things first, to give us a timeframe: this strip was published in “pulp” magazine Spicy Detective Stories between 1934 and 1943, then moved to Speed Detective Stories in a new format** until 1950 then, finally, to Crime Smashers until the comic’s demise in 1953.

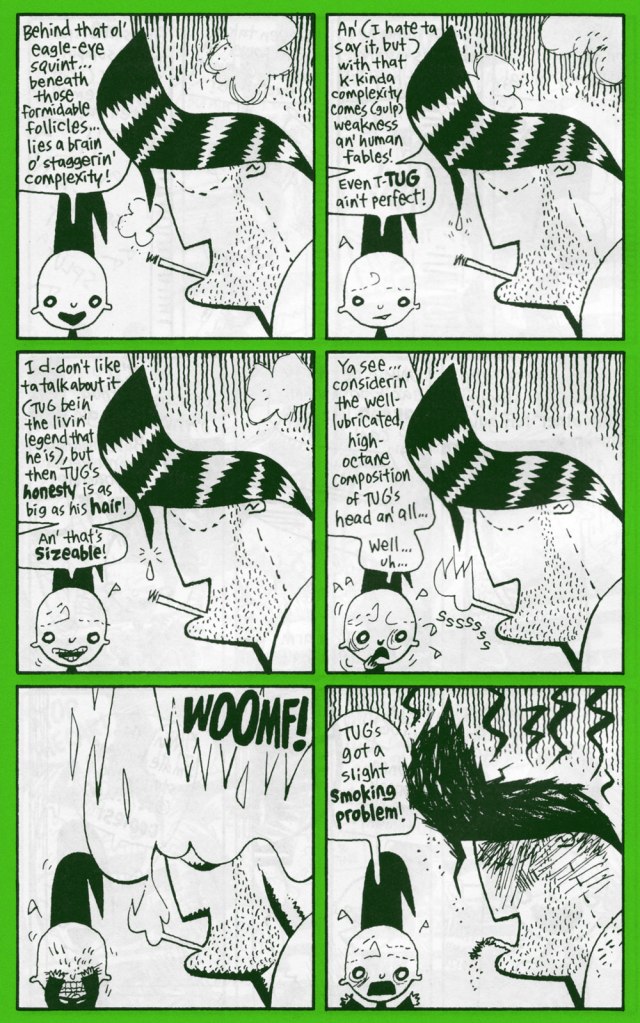

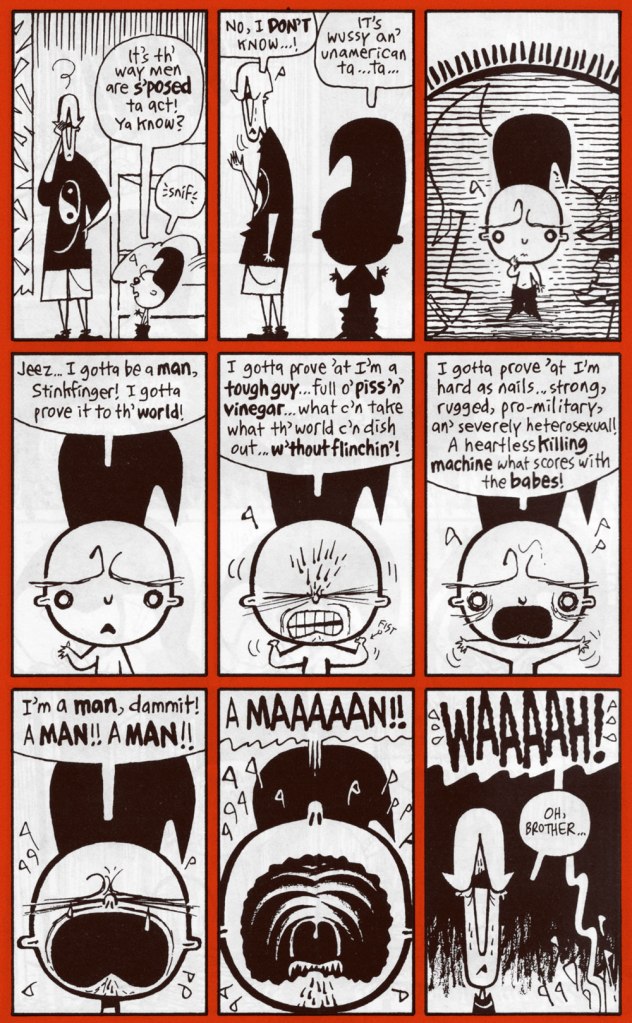

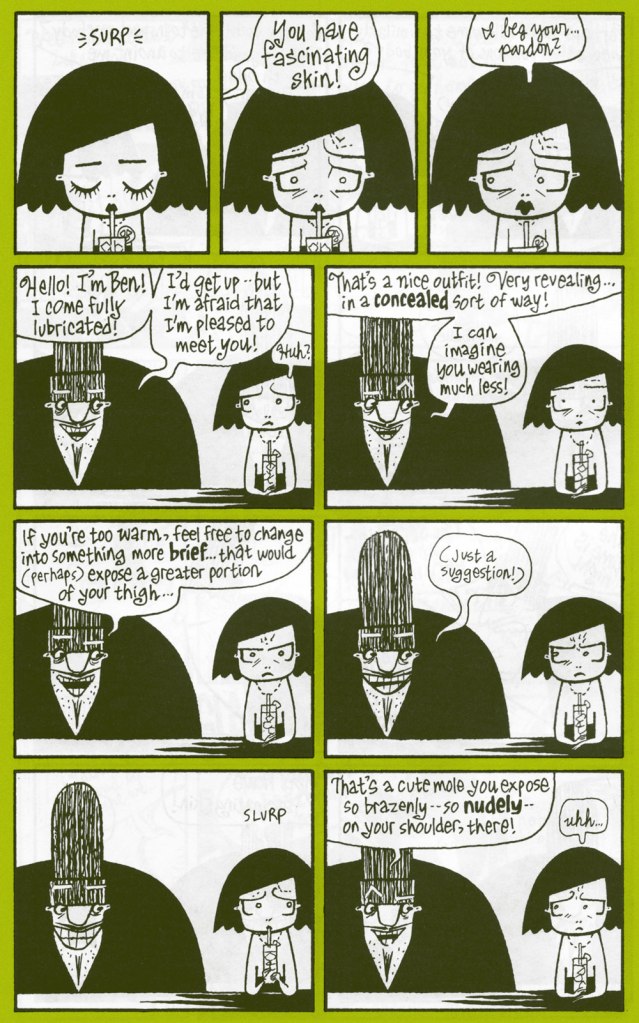

Sally the Sleuth features a tightrope act that’s not that easily achieved: fearless, self-sufficient Sally is so adept at spotting (and landing into the middle of) trouble that she frequently requires outside help to be rescued in the nick of time, with the role of the rescuer oft being played by her boss, the Chief, who usually bursts in through the door. What’s interesting is the way this rather typical damsel-in-distress set-up does not take anything away from our sense of Sally as a take-charge, go-getting kind of gal. She does not hesitate to bat her eyelashes or flash a gam when needed, but she’s neither the usual femme fatale archetype that appeared so often in contemporary comics, nor the innocent-yet-gorgeous victim. When captured, she spits (sometimes literally) in the face of her would-be killers; when she gets rescued, it was because she left instructions with Peanuts, her kid assistant, or schemed to leave the Chief enough clues to locate her if she hit a bad patch.

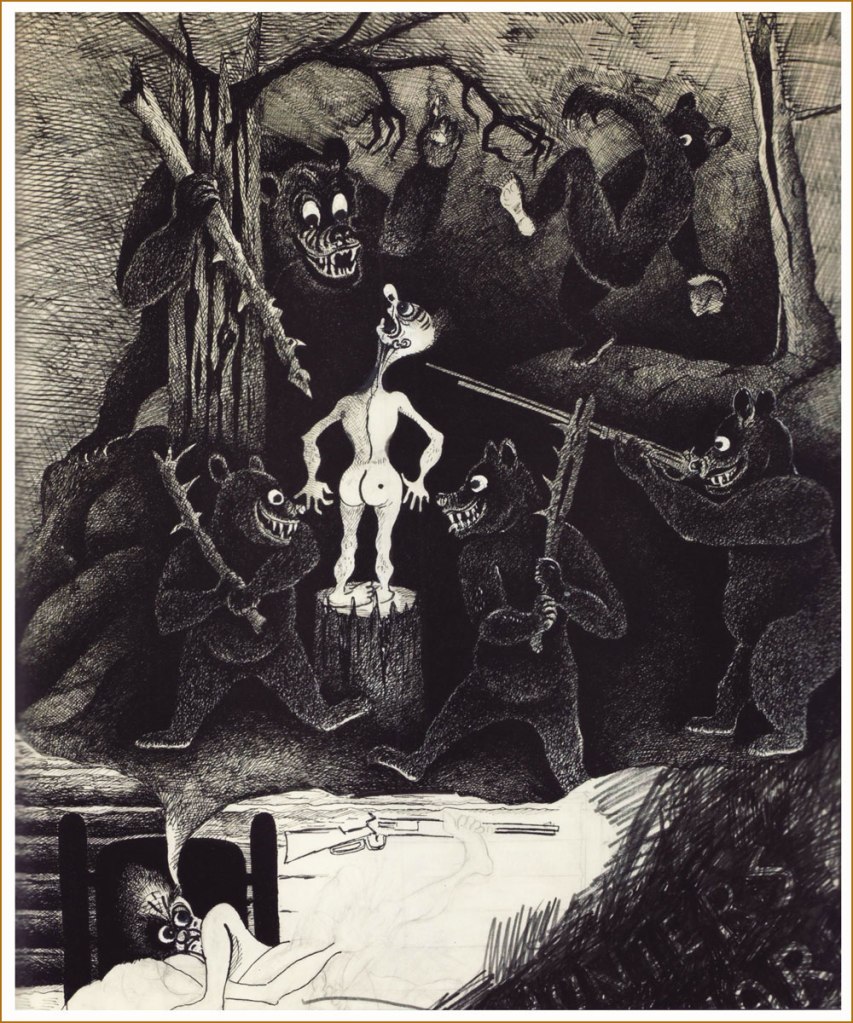

It may surprise a modern reader that an American comic from the mid-thirties (1935! consider this number again if it hasn’t sunk in yet!) should be so casual about a topless female when present-day consumers of culture freak out at the very sight of a nipple (and that goes for male nipples as well). Of course pulp magazines and comics weren’t read by staunch defenders of High Morals and Propriety, but it was nevertheless a hugely popular medium, and Spicy Detective Stories, where Sally got her débutante ball, certainly abounded in unclad women in tales of booze, butchery and concupiscence.

Which brings me to my next point: tension created by the play between the predictable and the unforeseen. Sally always, always ends up in a state of advanced déshabillé. That is an enjoyable given. Much like panties drop to the floor if a woman should be carrying celery, Sally’s dress and underwear fly off at the gentlest of tugs. However, just how it is accomplished varies wildly from week to week. One wouldn’t think that were so many interesting ways of getting accidentally undressed. And these stories are harsh, no doubt about it: scenes of torture and murder vary from the comparatively sedate (getting whipped, slapped, shot) to sensationalist (death by venomous snake or spider) to viscerally uncomfortable (cannibalism with more than a dash of necrophilia, being boiled alive, impalement).

Though of course it’s the nudity is sexualised, I love the ease with which Sally does it, completely unperturbed by having a bare chest whether she’s surrounded by hoodlums, talking to her boss, or racing through a crowded hotel. There’s a certain innocence in it, as if we were watching a frolicking Dedini nymph. Despite being so frequently assaulted, she does not at all come off as a victim.

Earlier-day Sally (1934-1943) is supposedly ‘ditzy and naive’ (source), but I think one should not mistake cheerfulness or pragmatism for naïveté. She navigates the seedy parts of town with aplomb and talent, efficiently following clues, taking on many roles to infiltrate criminal organisations or simply glean information. Sally may have to rely on the Chief to extricate her from yet another predicament, but he is a sort of handsome stock figure with little personality, mostly sitting around his office and agreeing when Sally says ‘I should investigate this!’

Sally the Sleuth has historical importance, if only for the panel borrowed by Frederic Wertham for his Seduction of the Innocent report from a Sally the Sleuth: Death Bait (1950) story. In the wonderfully written introduction to the Sally the Sleuth Collection, comics historian Tim Hanley goes a step further, saying “without Sally the Sleuth, there would be no Superman. Without the pulp heroine with a penchant for solving crimes in a state of undress, there would be no Batman either.” It can be (and has been) argued that he is giving this strip too much credit***, but there will be no argument that Sally is an important figure. Because I’m a philistine, what’s most important to me… is that it’s a great read.

~ ds

* As far as Barreaux, born Adolphus Barreaux Gripon, is concerned, there are much better places to read about his biography than on this blog, mostly due to the fact that biographies kind of bore me. I specifically direct you here for a detailed biography, and here for more information about Barreaux’ mixed heritage and the variety of genres he illustrated.

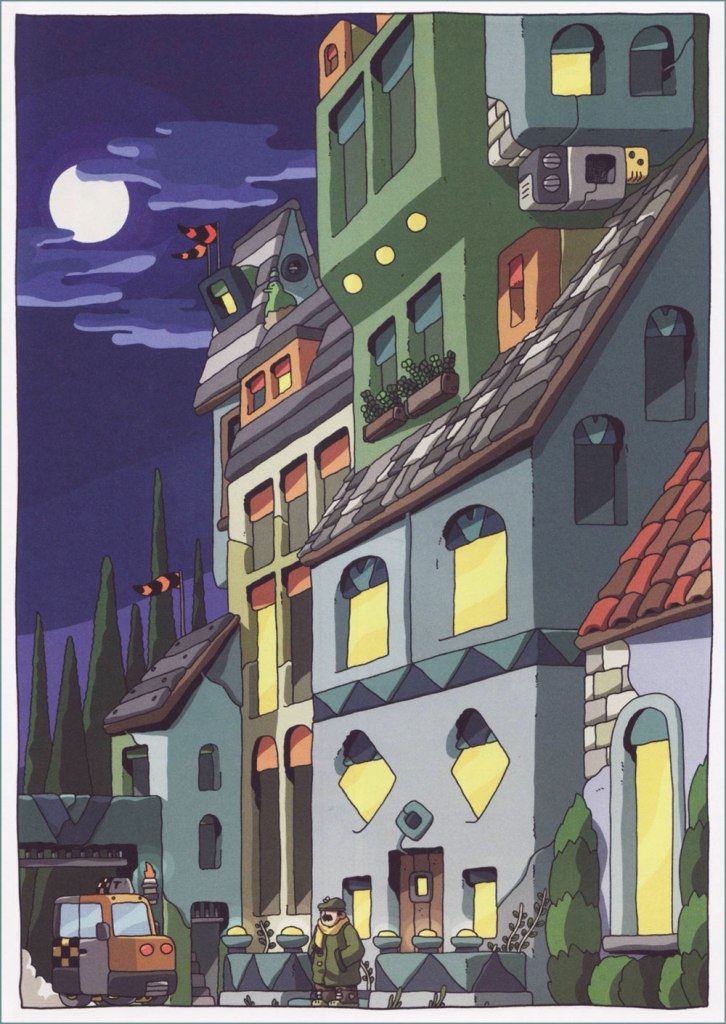

** This post only includes strips from the earlier, 1934-1943 version, because I by far prefer it to what came later, although I may be in the minority. The art got arguably better once Sally moved to Speed Detective stories, and stories also got longer, allowing for more elaborate plots. However, Sally was now some sort of international spy, travelling to ‘exotic’ countries and having to contend with native Hula dancers, superstitious savages in Indian jungles, Nazis, Japanese master-minds, and so on. She got disrobed less frequently, but the charming innocence of the strip, despite its violence and simple but effective art, is what makes Sally so appealing to me.

*** Hanley has been clearly reproached for this by some readers, and so elaborated on his blog:

My introduction begins with the grandiose claim that there would be no Superman without Sally the Sleuth, but it’s true. Long before Harry Donenfeld launched DC Comics, he was a publisher of pulp magazines that featured lurid crime stories. Sex was a major focus, and the dirty stories were a popular product. In 1934, Adolphe Barreaux convinced Donenfeld to expand outside of prose and add some comics to his books, and the “Sally the Sleuth” strip in Spicy Detective was their first attempt. It proved popular and more followed. Eventually, Donenfeld got into the comics game full time in the late 1930s, first with Detective Comics and later with Action Comics. Once Superman and Batman took off with young readers, more series followed and the comic book business became Donenfeld’s priority. But it all started with Sally.