« … devolving into a downright National Socialist muck of murderous paranoïa, a Lord of the Flies for our new century… »

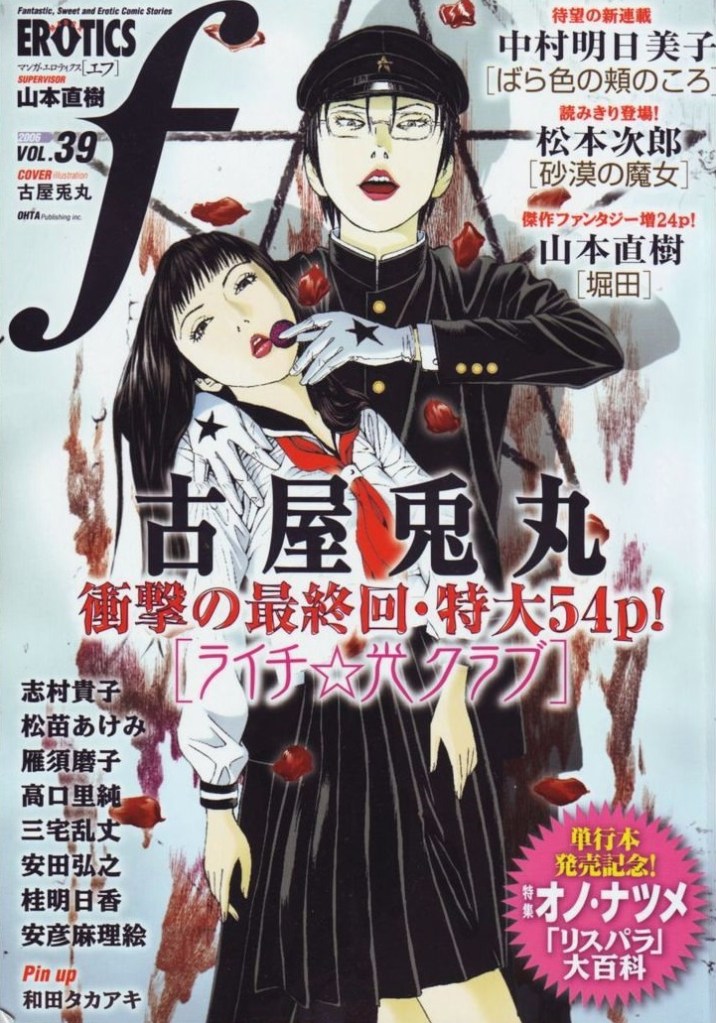

Lychee Light Club, aka Litchi Jirai Club (ライチ☆光クラブ), is a manga written and illustrated by Usamaru Furuya, who was smitten by a theatre play of the same name after watching it in 1985 as a high school student. Years later, he recreated it in manga form, albeit with a somewhat modified plot. It was serialized in Ohta Publishing’s Manga Erotics F* (May 7, 2005 – May 3, 2006). As for the play, it was directed by Norimizu Ameya** for the theatrical group Tokyo Grand Guignol (it’s funny to see the French ‘guignol‘ in this context).

Lychee Light Club‘s over-the-top violence elicits the occasional chuckle (one of its characters dies from somebody pitching a toilet through his midsection), and more than one wince of discomfort, too, as its schoolkids maim, bash and burn their way through the story. The premise is simple – Lychee Light club (more of a cult, really) consists of eight barely-teenage boys who worship youth as the ultimate symbol of beauty (and, consequently, hate all things adult). They have nice digs where they spend all their time after school – an abandoned factory with plenty of dumped implements useful in their pursuit of the sadistic. They are led by the charismatic and cunning ‘Zera’ (actually, Tsunekawa from class 2), whose charm and fine features inspire blind devotion from his gang, not to mention occasional sexual favours.

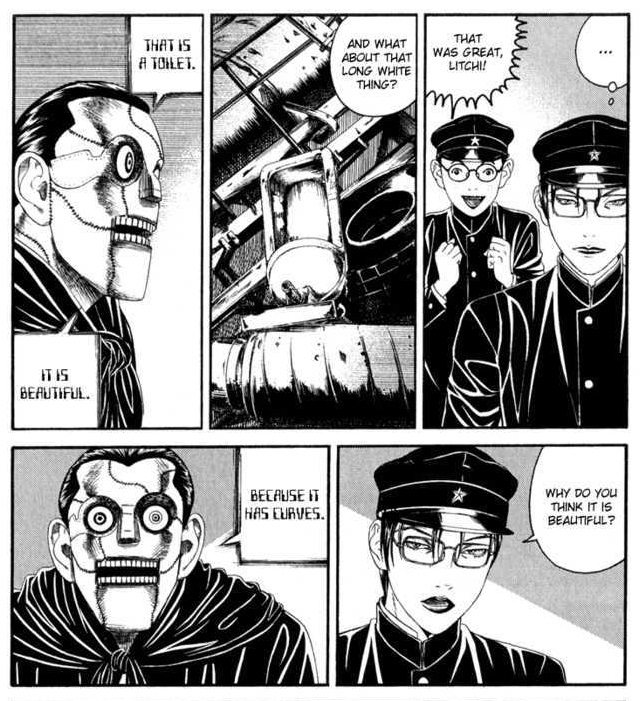

To pursue their vision of eternal youth and a universal, if unfocused, lust for power, the posse builds a mostly robotic ‘thinking’ machine-cum-Frankenstein-monster, all metallic parts except for a human eye ‘borrowed’ from Zera’s number Eins, Niko. Zera informs his crew that he planted lychee seeds in a landfill three years ago… and now they have a forest of trees heavy with fruit at their disposal as fuel for Lychee, their mechanical prodigy. Apparently Zera is also a brilliant agriculturist, for lychee trees are notoriously slow to bear fruit, and three years later he’d have a forest of greenery at best. ***

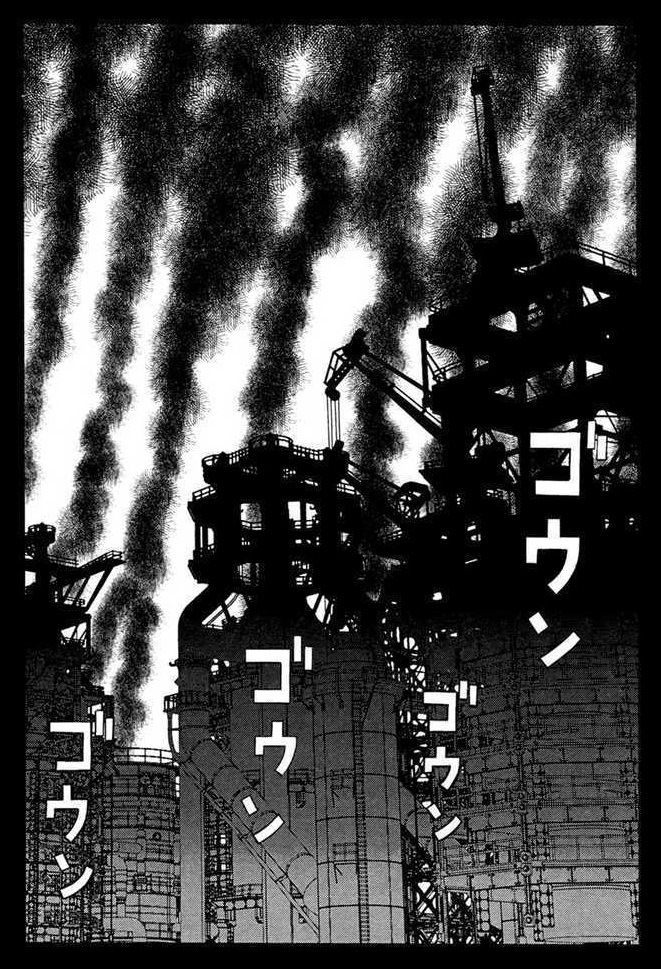

The story’s settings immediately plunge the reader into a kind of claustrophobia – filthy streets, a sooty factory, trashed cars — clearly an industrial town which doesn’t offer much hope for a better future. The boys’ lives outside the club are barely discussed, but the story hints that they all come from an uncomfortable family situation, though apparently they’re all ‘good kids’, as their maths professor incredulously notes before she is gleefully tortured and murdered.

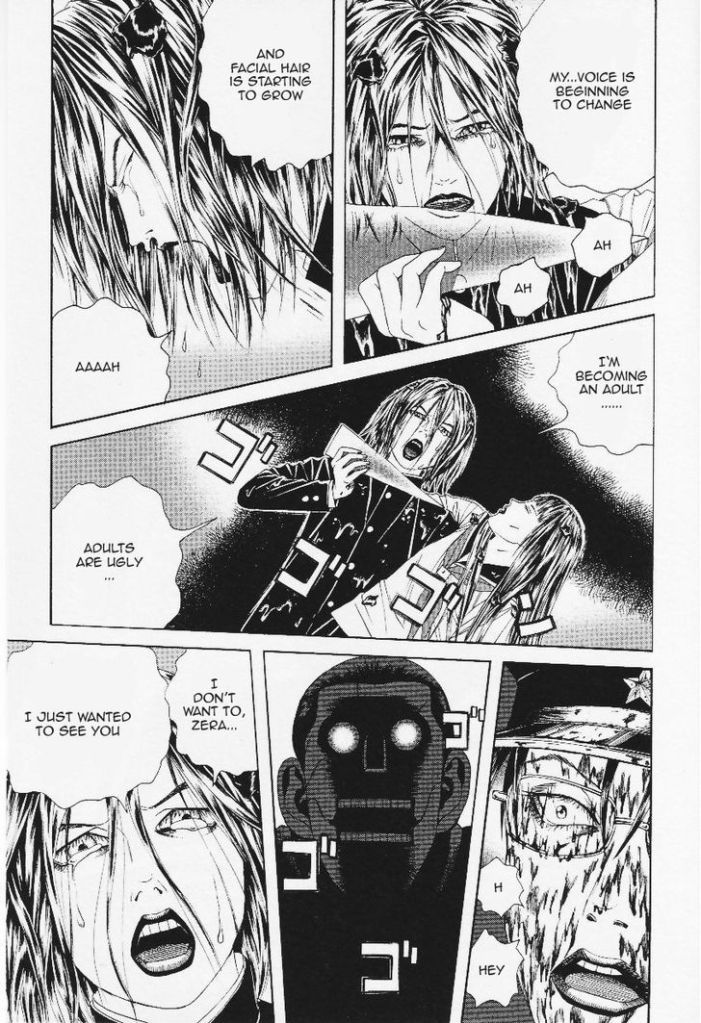

There is a strong current of body dysphoria running through Lychee Light Club, fitting for a set of characters so fixated by ‘beauty’. The megalomaniac Zera is obsessed with Elagabalus, a Roman teenage emperor known for his sexual decadence (apparently to the point of standing out for his outlandish vices among other Roman emperors centuries later, which is surely a feat of some kind, given what some of them got up to).

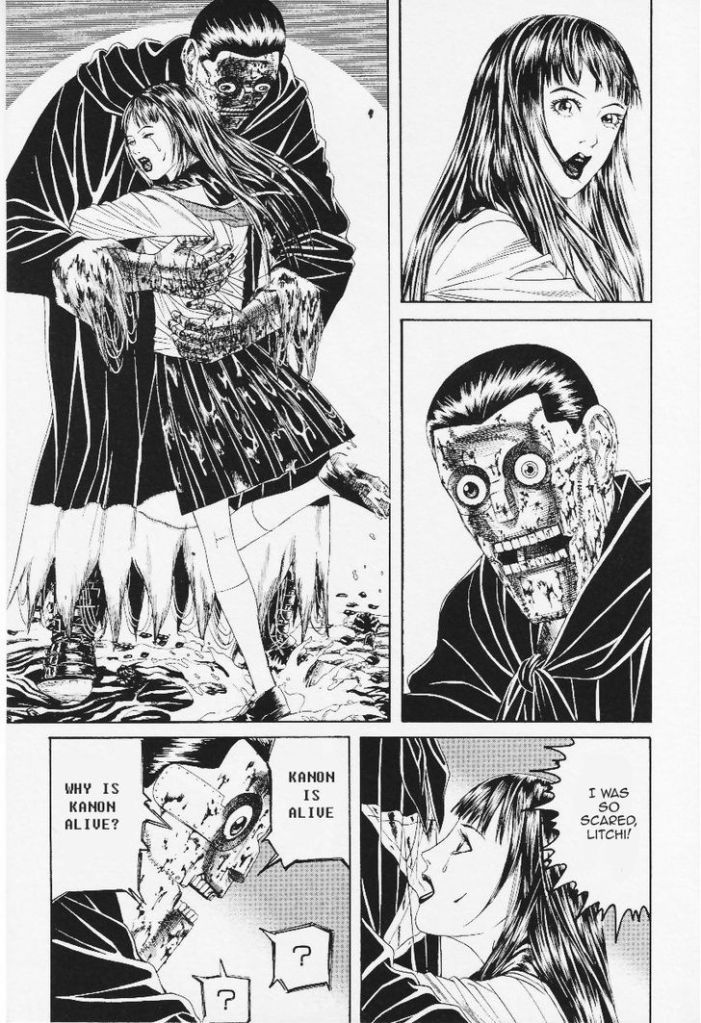

In a sort of Peter Pan/Neverland situation, the boys are nauseated by the sight of an adult woman’s body (her breasts are qualified as ‘repulsive, swollen lumps of fat’), and horrified by her ‘ugly’ innards, wondering whether their own organs are ugly, too (plot spoiler: they are, indeed). They obsess over Kanon, the eventual heroine of the story, because she’s soft and beautiful (but hasn’t turned into a woman yet). Kanon herself doesn’t want to grow up because she’s worried Lychee (at that point ‘humanized’ by her love) will reject her adult self.

All of them need to urgently get to therapy, but instead of that eyeballs are ripped out, innards (not to mention semen) are spilled, and the whole thing ends in an utter bloodbath, leaving the only ‘innocent’, Kanon, mourning Lychee, who is now more ‘human’ than the members of the Lychee Light club because he understands that murder is wrong. Reading this manga is a bit like observing a train wreck. Nothing in this story is nearly as profound as it pretends to be, and plot holes bloom much like lychee flowers — and yet its mostly naïve characters stick in one’s mind. Poor, poor children.

« …a mere plaything, having feelings! »

~ ds

* Speaking of the erotic… a quick perusal of blurbs quickly yields ‘Shocking, sexy and innovative, the Lychee Light Club is at the pinnacle of modern day Japanese seinen manga (young adult comics)‘, with which advertisement I have several bones to pick. ‘Sexy’ is an uncomfortable description of a manga with sadistic violence and heavily underage protagonists, though eroguro fans probably lap the former up. As for the ‘young adult comics’ bit, I’d like to submit a petition to stop assuming that stories about teenagers are meant to be necessarily read by teenagers. Should ‘old’ people read exclusively about the elderly? One can argue that adults aren’t so interested in reading about to-be-adults (my case in point, Wheel of Time book one, which I recently read, and whose adolescent protagonists were intensely annoying), but that speaks more to a lack of storytelling ability.

** Who’s had a wild enough (perhaps ‘unhinged’ would be a better description) life that he would merit an entire article by himself (see a summary here).

*** As far-fetched as this plot is is, the anime by the same name (loosely based on the manga) is hilariously goofy where the manga was highfalutin. Take the plot of episode number 6, in which ‘Some members of the club wonder if Lychee really only runs at lychee fruit and then offer him a peach. As he accepts it, they give various other foods and eventually Lychee develops culinary skills.’