It’s nearly New Year’s eve, and a Friday, which seems like some sort of omen for a gallery of vintage winter postcards featuring toadstools, seeing as Fungus Friday is every bit as tangible as Tentacle Tuesday (go here if you’re late to the tentacle train). The connection between hibernal celebrations and mushrooms might not be an immediately obvious one, but one has to keep in mind that the way we celebrate Christmas is distinctly pagan.

More in reference to mushrooms, it has been argued that Santa Claus actually started out his folkloric life as a shaman who gets high on Amanita* (either by direct consumption, or by drinking the urine of reindeer who have consumed them). When one looks for coincidences, one finds them, but nevertheless it’s worthwhile pointing out that the pine trees we adorn our households with for Christmas form a symbiotic relationship with Amanita muscaria (yes, that iconic red toadstool with white warts that so often stands in for a generic mushroom in many stories), and that Santa Claus’ red-and-white costume follows its colours. For more in-depth analysis, I highly recommend Santa Claus Was a Psychedelic Mushroom (written by Derek Beres, who also coined the great alliteration ‘psychedelic piss’ when discussing reindeer-processed Amanitas).

This claim has been disputed by people (some of whom were foaming at the mouth, and not necessarily from mushroom consumption) who point out that this is rather a case of retro-fitting facts into the storyline. You may accuse me of intellectual laziness, but I actually don’t give a fig about where Santa Claus came from. Of more relevance to me (and this post) is this bit: ‘Fly agaric does not appear in authentic Germanic Christmas cards, they’re New Years cards which use fly agaric as a good luck symbol, alongside horse shoes and four-leaf clovers.’ The Fliegenpilz is indeed a good luck charm in Germany, so that’s quite possible. New Year’s card are certainly germane to this time of year, now that the ecstatic joys of Christmas (ahem) are a week behind us.

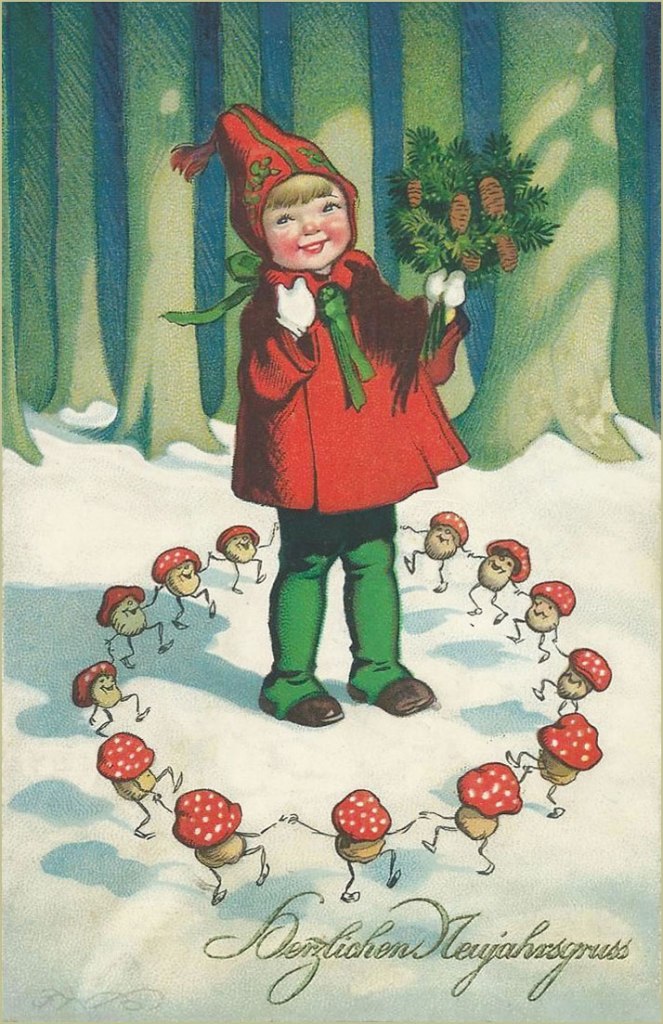

Either way, enjoy the array of vintage postcards from the late 1930s-1940s, most of them German. Whatever they’re supposed to symbolize (the ones with writing do mention New Year, not Christmas), to a modern reader’s eyes they’re delightfully weird, and I won’t blame anyone for thinking that some drugs were involved.

The Amanitas-as-good-luck-charm theory seems to be borne out in the following, given the presence of clover, horse hooves, etc.:

Who knew so much revelry was taking place around a couple of mushrooms?

The rest of these are in German:

Happy New Year to all our dear readers, and may your paths be littered with tasty mushrooms in the coming year!**

*Amanita muscaria is considered poisonous, as far as foraging mushrooms go, though it has a long history of being used as a psychedelic/intoxicant by many tribes (namely, by the indigenous people of Siberia). A strong dose causes delirium and a host of other side-effects, which fade after a few days. I might add that some Russians (and god knows Russians will eat whatever mushroom is even remotely edible – I say that with nothing but admiration) consider it a good edible, provided you boil it in water three times or so. I might try that one of these days! I have no interest in psychedelic properties, but plenty of interest in culinary ones.

**Assuming you like them, of course.

~ ds